This article was co-authored by wikiHow staff writer, Jennifer Mueller, JD. Jennifer Mueller is a wikiHow Content Creator. She specializes in reviewing, fact-checking, and evaluating wikiHow's content to ensure thoroughness and accuracy. Jennifer holds a JD from Indiana University Maurer School of Law in 2006.

There are 8 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page.

This article has been viewed 11,703 times.

Learn more...

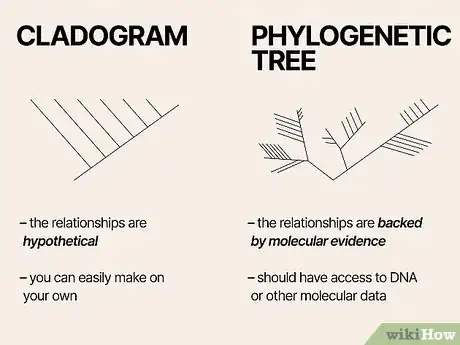

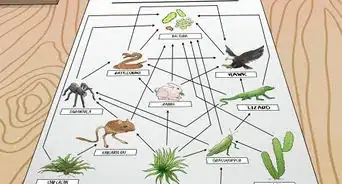

Cladograms are an important tool used by scientists to understand common ancestors and the characteristics of certain animals. If you're studying evolution in biology, you're likely to encounter a cladogram. At first glance, these diagrams can seem pretty complex, but they're pretty simple once you know where to start. Cladograms are meant to show the ways that some animals potentially evolved to have specific traits or characteristics, such as a backbone or four limbs. Along the way, you might uncover some really interesting similarities you never would've thought about before! Read on to learn everything you need to know about interpreting a cladogram, including how to make your own.

Things You Should Know

- Use cladograms to find hypothetical evolutionary relationships between different organisms.

- Trace evolutionary changes by following the main line of a cladogram from the beginning to the end.

- Discover similarities between different animals by identifying their common ancestor as a node on a cladogram.

- Make your own cladogram by choosing 3-4 animals and showing their evolutionary relationship based on specific characteristics.

Steps

Interpreting a Cladogram

-

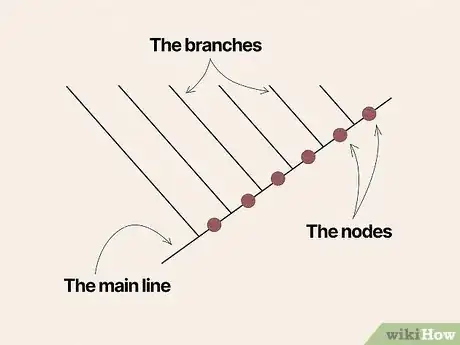

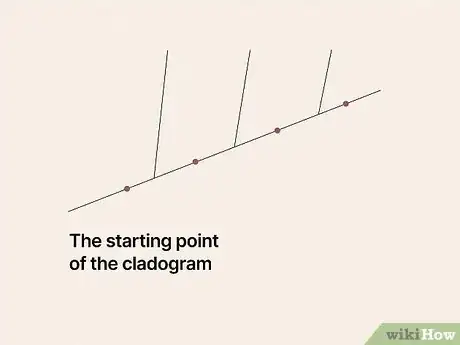

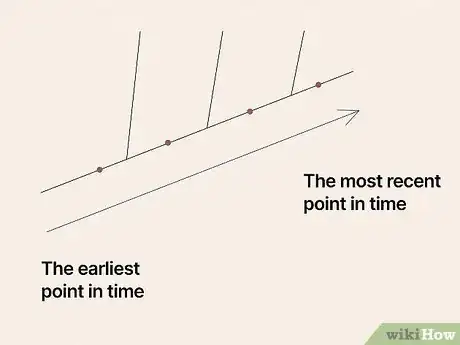

1Locate the starting point of the cladogram. Every cladogram has a main line that represents time. The line starts at one end before there are any branches.

- The starting point is usually the bottom-left, but it might be a different spot depending on the orientation of the cladogram you're looking at. Orientation doesn't matter with cladograms—they still convey the same information regardless of how they're turned.

-

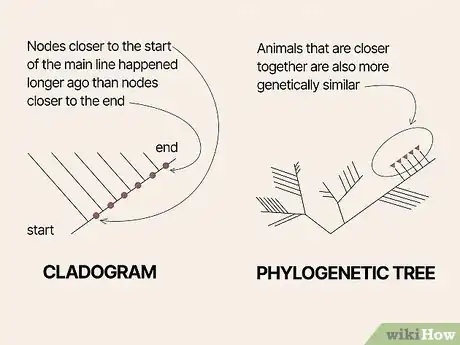

2Move up the main line of the cladogram to move forward through time. That starting point you identified is the earliest point in time represented on the cladogram you're looking at. The opposite end of the cladogram is the most recent point in time. The position of a node on the line indicates the relative point in time when that particular characteristic or trait evolved.[3]

- Lines on a cladogram aren't drawn to scale. In other words, the main line doesn't start or end on any particular year and the distance between nodes doesn't correspond to any particular range of years.

- Since the lines aren't drawn to scale, you can't infer how long ago any particular characteristic evolved. You can only infer whether a characteristic evolved before or after another characteristic represented on the cladogram.

-

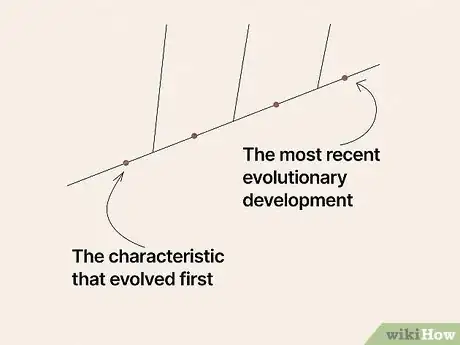

3Use the position of the nodes to determine which characteristics evolved first. The node closest to the start represents the characteristic that evolved first relative to the other characteristics represented by the cladogram. The next one up from that was the next characteristic to evolve, and so on until the last node, which represents the most recent evolutionary development.[4]

- For example, if the node closest to the starting point of the main line represents "teeth" and the node halfway up the main line from the starting point represents "lungs," you can infer from the cladogram that animals evolved teeth before they evolved lungs.

- Remember that since the lines don't represent specific dates or ranges of dates, you can't say exactly how long it took for these evolutionary developments to happen—only the general order in which they happened.

-

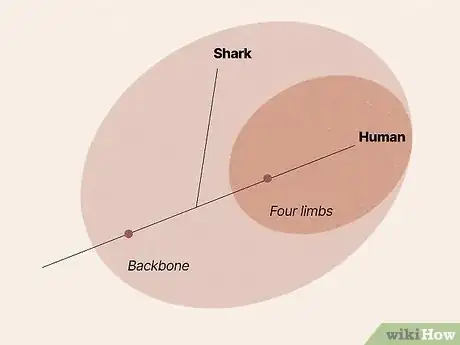

4Determine differences in animals based on where they branch off from the main line. An animal branches off the main line at the point that its evolution diverges from the other animals depicted on the cladogram. It doesn't have any of the characteristics beyond the node where it branched off.[5]

- For example, imagine a simple cladogram that includes the characteristics "backbone" and "four limbs." Two of the animals are sharks and humans. Both sharks and humans have backbones, but sharks don't have four limbs. Sharks would branch out from the main line at the backbone node.

-

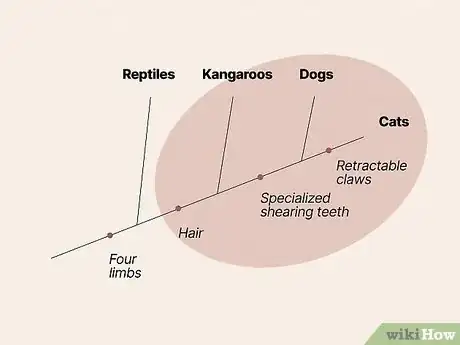

5Relate the animals to each other based on the characteristics they share. Larger groups of animals have a common ancestor further back in time. If you start at the first node of a cladogram, all of the animals that branch off after that node have the characteristic indicated by the first node in common.[6]

- For example, suppose you're looking at a cladogram with nodes for four limbs, hair, and retractable claws. The animals represented on the cladogram include reptiles, kangaroos, dogs, and cats. Of these animals, you could say that kangaroos, dogs, and cats all share 2 of the characteristics (four limbs and hair).

- In this example, reptiles would be considered an outgroup—they only have 1 characteristic in common with the other groups, and likely have significantly more differences. On a cladogram, they're the first animal that branches off the main line.[7]

Making a Cladogram

-

1Choose 3 or 4 animals for the endpoints of your cladogram. The largest cladograms analyze hundreds, or even thousands, of organisms and use computers to compile the data and generate the resulting diagram. But if you narrow that down to just a few animals, you can pretty easily make a cladogram yourself.[8]

- For example, you might choose dogs, cats, horses, and turtles.

-

2Find a characteristic that all of your animals have in common. The first node on your cladogram represents a common ancestor that evolved one characteristic that all of your animals have in common. This characteristic is also the first characteristic to evolve out of all the characteristics that will eventually be included on your cladogram.[9]

- For example, dogs, cats, horses, and turtles all have a backbone, so that could be the first node on the main line of your cladogram—the common ancestor all of these animals have in common that developed a backbone.

-

3Brainstorm other characteristics the animals have. Try to come up with around twice the number of characteristics as you have animals. Make a table and run your list of characteristics down the left side. Along the top line of the table, make a column for each animal you want to include in your cladogram. Then, you can simply place a checkmark in the row for the characteristic if the animal in that column has it.[10]

- For example, you might list backbone, hooves, walks on 4 legs, carnivorous, hair/fur, warm-blooded, mammary glands, and retractable claws. Then, you would place checkmarks in the "horse" column for all of those traits except for retractable claws.

-

4Narrow down your list so one animal branches off at each node. Look at your table to find 1 trait that all of the animals have, 1 trait that all but one animal has, another trait that all but 2 animals have, and so on. If you hit a block here, brainstorm more characteristics until you find one that fits.[11]

- To return to the previous example, you can see that only horses have hooves, so you can eliminate that characteristic—since no other animals have it, you have nothing to compare them to.

- Cats, on the other hand, are a strong contender for the final slot because they have all of the traits (except hooves, which you've eliminated).

- Since all animals have 4 legs and all animals have a backbone, you only need one of these characteristics for your first node—you can eliminate the other one.

-

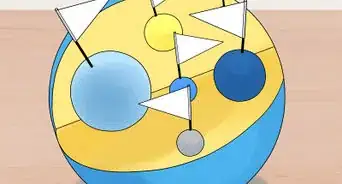

5Draw concentric circles to illustrate which animals have which characteristics in common. The largest circle represents the characteristic that all of your animals have in common. Then, draw a smaller circle inside it that represents a characteristic some, but not all, of the animals have.[12]

- For the example with dogs, cats, horses, and turtles, your largest circle would be the "backbone" circle, because all of your animals have one of those. Inside that circle, you'd draw a circle for warm-blooded, which captures all of your animals except turtles. Then, you'd have a smaller circle for "carnivorous," with the smallest circle going to "retractable claws."

- Label each of your animals in the circle that represents the last characteristic it has in common with the other animals before it diverges. In the above example, turtles would go in the largest circle, then horses in the next-largest, then dogs, with cats in the smallest circle.

-

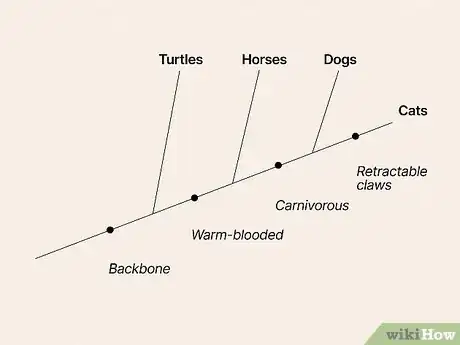

6Create a cladogram from your concentric circles. Draw the main line of your cladogram diagonally from the bottom-left corner to the top-right corner. Create a branch a little way up from the starting point at the bottom-left corner. Then create the rest of the branches at intervals up the line until you get to the end.[13]

- In the example, turtles would branch off first, from the node that represents "backbone." Your next node would be "warm-blooded, " with horses branching off from it. Then you would branch of dogs from the "carnivorous" node, leaving only cats after the "retractable claws" node.

References

- ↑ https://evolution.berkeley.edu/phylogenetic-systematics/reading-trees-a-quick-review/

- ↑ https://evolution.berkeley.edu/phylogenetic-systematics/reading-trees-a-quick-review/

- ↑ https://www.nausetschools.org/cms/lib/MA02212418/Centricity/Domain/204/Phylogeny%20Review%20Worksheet%202017.pdf

- ↑ https://www.nausetschools.org/cms/lib/MA02212418/Centricity/Domain/204/Phylogeny%20Review%20Worksheet%202017.pdf

- ↑ https://www.nausetschools.org/cms/lib/MA02212418/Centricity/Domain/204/Phylogeny%20Review%20Worksheet%202017.pdf

- ↑ https://www.cbsd.org/cms/lib/PA01916442/Centricity/Domain/2169/Pearson%20Chapter%2018.2.pdf

- ↑ https://evolution.berkeley.edu/phylogenetic-systematics/reading-trees-a-quick-review/

- ↑ https://ucmp.berkeley.edu/clad/clad2.html

- ↑ https://www.education.txst.edu/ci/faculty/dickinson/PBI/PBISpring07/AlienInvasion/Content/Making%20Cladograms.pdf

- ↑ https://www.bu.edu/gk12/eric/cladogram.pdf

- ↑ https://www.bu.edu/gk12/eric/cladogram.pdf

- ↑ https://www.education.txst.edu/ci/faculty/dickinson/PBI/PBISpring07/AlienInvasion/Content/Making%20Cladograms.pdf

- ↑ https://www.education.txst.edu/ci/faculty/dickinson/PBI/PBISpring07/AlienInvasion/Content/Making%20Cladograms.pdf

- ↑ https://evolution.berkeley.edu/phylogenetic-systematics/using-trees-for-classification/

- ↑ https://academic.oup.com/bioscience/article/62/8/757/244348?login=false