This article was co-authored by Bryce Warwick, JD. Bryce Warwick is currently the President of Warwick Strategies, an organization based in the San Francisco Bay Area offering premium, personalized private tutoring for the GMAT, LSAT and GRE. Bryce has a JD from the George Washington University Law School.

There are 15 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page.

This article has been viewed 61,494 times.

Retaining knowledge is important for success at school and in the workplace. While there’s no set rule for how much people will forget over a given amount of time, everyone will sometimes struggle to remember important information. However, it’s possible to strengthen memorization skills and ensure that important knowledge is retained.

Steps

Retrieving Information

-

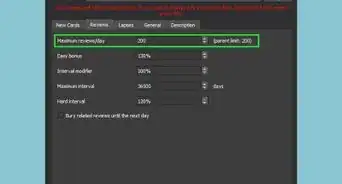

1Use spaced repetition. If you want to remember something, don’t repeat it over and over to yourself – this is known as massed repetition.[1] Instead, let some time elapse before you repeat it. Ideally, you want to try to retrieve the information exactly at the moment when you were about to forget it.[2] The difficulty of retrieving the information correlates to how strongly you will remember it.

- If you’ve just met someone and want to remember their name, repeat it to yourself every five or ten seconds while talking to them.

- When studying, don’t go over the same flashcards over and over again. Let a few hours or even a day go by, then go through them again. You can stop studying the ones that are easy to remember. Focus on repeated the ones that are difficult, but always allowing some time to elapse in between sessions.

-

2Quiz yourself. Taking a short test helps to keep information you’ve just learned in your mind. The process of retrieving the information from your brain seems to strengthen your mental connection to it, making it easier to remember that information over the long term[3]

- When reading, stop every so often – perhaps after every chapter or section, or more often it’s very difficult reading. Put down the reading and ask yourself, "Can I summarize what I have just read in one or two sentences?"

- If you’re going to be tested on the information, ask yourself questions in the style they’ll appear on the test. For instance, define the meaning of vocabulary words if the test will have fill in the blank questions.

- After a lecture, class, or important meeting, jot down the main take-away points in your own words. Don’t look back at your notes: see what you can remember.

Advertisement -

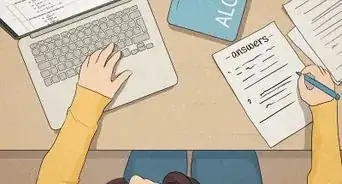

3Take notes long-hand. Even if you only use your laptop for note-taking, and stay away from distractions like e-mail or social media, typing is still less effective than hand writing your notes.[4] Writing by hand is slower and forces you to put the teacher’s words into your own words. This is the first step toward understanding and retaining knowledge, rather than merely recording it.

-

4Explain your knowledge to someone else. Teaching the knowledge you need to retain to a friend, roommate, or family member forces you to translate the information into clear, understandable language. This is an important activity in “active learning,” which has been shown to improve retention and understanding of knowledge.[5]

- Spend two minutes explaining a concept to your roommate. Then, swap roles, and let your roommate explain a concept to you for two minutes.

- Grab a whiteboard and teach a five-minute lesson to a friend. Then, ask your friend to explain what you’ve just taught them. Pay attention to what confused them: the areas that you explain least clearly are probably the things you understand least well.

- Write a letter to a parent or other relative. Explain the concept in clear, simple terms.

-

5Take breaks when studying. You need to allow time for mental recovery and for the information you’re learning to be absorbed. Even while you’re on your break, your mind will be turning over the new information, and you might find yourself better able to understand a problem when you return to it.[6]

Creating Connections

-

1Link your knowledge to larger concepts. It’s much easier to remember facts if you understand why those facts are true. Ask yourself, or your teacher: why do things work the way they do? If you understand the larger conceptual framework, you will be able to retrieve knowledge more easily and even guess more accurately.

- For example, if you have to memorize geographical borders, think about how those borders were formed. Notice that in many places, borders follow natural features such as rivers and mountain ranges. By observing a general rule like this you save yourself from having to memorize each individual border; instead, you can remember which borders follow this rule.

-

2Connect facts to ideas. You are more likely to remember something if you can associate it with other, related things. Tell a story to yourself about a particular fact: even if your story is light-hearted, it will cement the fact in your mind.

- This is sometimes call the Baker/baker paradox. Shown a picture of a woman, people are much more likely to remember that she is a baker than that her name is Baker. This is because the idea of being a baker has more associations. It conjures up thoughts of bread and might suggest links with the image: perhaps her face looks doughy, for example.[7]

-

3Evaluate your own learning process. Assess yourself by asking whether you are absorbing new material and whether you understand the big concepts that underlie that material. Reflect on what aspects of the learning process have worked for you and what aspects were less helpful. This kind of self-evaluation is known as metacognition, and it has been shown to improve your ability to transfer what you’ve learned to new settings and situations.

-

4Opt for the final project. Sometimes you are allowed to choose between taking a final exam or completing a final project. In other cases, you might have the choice to take a class that assigns a project. Where possible, choose the final project. Completing a complex project related to the knowledge area is associated with greater retention of knowledge than taking a test alone.

-

5Don’t focus on just one thing for too long. Instead, turn from one task to another, and intersperse studying one subject with studying something else.[8] Look for connections between the different topics. Seeing how knowledge fits together into a larger picture will help you to understand its significance and remember it better.

Varying Learning Modes

-

1Present the information in different ways. By learning the same material in different modes, you will increase your ability to remember it.[9] Regardless of preferences, everyone can benefit from learning the same information visually, aurally, textually, and so on.

- Many people feel or have been told that they are more of a “visual learner,” an “auditory learner,” and so on. There’s no evidence to suggest, though, that learning mainly in your preferred mode is advantageous.[10] Instead, it’s helpful to learn in as many different modes as possible.

-

2Make up a little song about the information. Music accesses different parts of the brain, and the ability to remember music seems to have evolved earlier than the ability to process language.[11] Singing about your topic helps you store that information in a different part of your brain.

- If you’re studying a foreign language, learn a familiar children’s song in that language to solidify vocabulary. For example, “Heads, Shoulders, Knees, and Toes” will help you memorize that language’s words for major body parts.

- You probably learned to count partly through nursery rhymes such as “Five Green and Speckled Frogs.”[12] Make up similar silly songs about concepts in trigonometry or calculus – it still works!

- Share your song with your study group. Singing in a group has profound benefits for your brain.[13]

-

3Create a mental image related to the information. This method builds on the importance of creating mental associations with an idea in order to remember it. A short scenario or picture in your mind will create a richer set of associations and allow you to remember abstract ideas more concretely.

- Memorize the difference between the mathematical concepts of “zero slope” and “no slope” by picturing a skier. When the skier gets to a vertical cliff, she will scream, “No slope!”

-

4Draw a concept map. This is a visual representation of a set of related ideas. Use words and drawings as well as arrows to indicate relationships. [14]

- Concept maps can be very helpful in representing and remembering hierarchical relationships. However, they can also foster creativity, because it’s possible to visualize relationships in many dimensions instead of along one single line.

- The flow chart is one kind of concept map.[15] It represents a procedure or decision-making process, representing steps in symbols and connecting those steps using arrows.

-

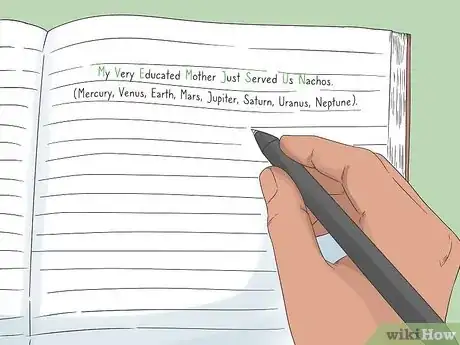

5Use mnemonics. These are devices to aid memory, often using poems, sayings, or initials. They should be catchy, funny, and easy to repeat.[16]

- For example, the order of the planets can be remembered using the phrase “My Very Educated Mother Just Served Us Nachos” (Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune).

- The fates of King Henry VIII's six wives is often remembered through a simple, mostly-accurate poem: “Divorced, Beheaded, Died; Divorced, Beheaded, Survived.”

References

- ↑ https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/living-mild-cognitive-impairment/201403/spaced-repetition

- ↑ https://hbr.org/2019/10/where-companies-go-wrong-with-learning-and-development

- ↑ https://learningcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/enhancing-your-memory/

- ↑ https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0956797614524581

- ↑ http://www.duq.edu/about/centers-and-institutes/center-for-teaching-excellence/teaching-and-learning/active-learning

- ↑ http://ww2.kqed.org/mindshift/2014/08/25/how-does-the-brain-learn-best-smart-studying-strategies/

- ↑ https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/mental-mishaps/201002/large-mocha-without-name

- ↑ http://www.apa.org/gradpsych/2011/11/study-smart.aspx

- ↑ https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/2011/01/learning-styles-fact-and-fiction-a-conference-report/

- ↑ https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1539-6053.2009.01038.x

- ↑ https://www.rasmussen.edu/student-experience/college-life/most-common-types-of-learners/

- ↑ http://www2.ed.gov/parents/academic/help/math/part_pg5.html

- ↑ https://www.rasmussen.edu/student-experience/college-life/most-common-types-of-learners/

- ↑ http://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1000&context=mathcs_etd_masters

- ↑ http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/flowchart

- ↑ https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281733369_Mnemonology_Mnemonics_for_the_21st_century