This article was written by Jennifer Mueller, JD. Jennifer Mueller is an in-house legal expert at wikiHow. Jennifer reviews, fact-checks, and evaluates wikiHow's legal content to ensure thoroughness and accuracy. She received her JD from Indiana University Maurer School of Law in 2006.

This article has been viewed 21,656 times.

U.S. law is more than just statutes passed by legislatures. Appellate courts – including the U.S. Supreme Court – are responsible for interpreting those statutes, and that interpretation becomes part of the law itself. Therefore, to understand a statute and how a court will decide an issue arising under it, you must study written appellate court opinions. Researching case law begins with finding one case that discusses the legal issues you've identified, then using that case to find others that together point to a legal resolution for the problem at hand.

Steps

Identifying Legal Issues

-

1Evaluate the facts. Civil cases typically begin with a dispute, so researching case law begins by spotting the legal issues raised by the facts surrounding the dispute. At this stage, consider everything at face-value, and don't discount anything as not relevant.

- For example, if you were involved in a car accident and want to sue the driver of the other car, you'll want case law that deals with the duty of care of other drivers that relates specifically to the circumstances surrounding your accident. If the other driver hit you because she ran a stop sign, you should look for cases that involve accidents that occurred when one party ran a stop sign.

- Cases provide stronger support that have facts that are more closely related to the facts in your situation. All facts potentially are relevant in finding the most similar case, so you can argue that the rule the court applied in that case also applies to your situation.

- To continue the stop-sign example, if the accident occurred at night, you should be looking for cases where the accident occurred at night – even if visibility wasn't a serious issue in your case. The courts may have established a different rule for night driving that doesn't apply during the day.

- You also want to be on the lookout for underlying or tertiary issues. For example, if you want to research case law relevant to your divorce, there may be other issues involving property ownership, retirement accounts, or child custody. Those issues typically would have to be researched separately.

-

2Consider the relationship of the parties. The relationship of the parties prior to filing a lawsuit can affect the legal remedies available to the party who sued as well as the duties and obligations both parties have to each other.

- For example, some parties have a fiduciary relationship, which means one party owes the other a higher standard of care. Financial advisors and home-care providers are examples of professionals who have a fiduciary duty to their clients.

- A contractual relationship is another type of relationship that may be present. If the parties signed a contract, that document likely defines their relationship and their duties to one another.

Advertisement -

3Determine the desired outcome. To find cases that relate to the legal issues you've found and support your arguments, you must have an ultimate goal in mind, such as an award of money or legal recognition of rights.

- For example, suppose you want to know whether you can ask a court to order specific performance under a contract you entered in which the other party breached. While cases similar to yours that stand for the principal that the actions of the other party amount to breach of contract, you also want to focus on the remedy – whether the party who sued was entitled to anything other than monetary damages as a result of the breach.

- Similarly, if you're interested in what the maximum monetary award might be for a case such as yours, you would want to look for cases in which the amount of monetary damages was one of the issues before the court that issued the decision.

-

4Set initial limits for your search. Because you want to make sure that the cases you find have value to your legal argument, you must look for cases decided by courts in the state where the dispute occurred that deal with similar problems.

- In many ways, doing legal research is similar to researching anything else. The search limits you set at this stage are mostly based on common sense.

- For example, if you were doing research on a historical event, you might limit your search to the year the event took place or the geographical area where the event occurred.

- Similarly, if you're researching a legal issue, you want to limit your research to the relevant state or geographic area, and to relatively recent cases. Although it may be interesting, you probably won't get much value from a case decided 100 years ago.

Finding the Most Relevant Cases

-

1Head to your local law library. Most county courthouses have a public law library, where you can use most assets free of charge as well as get research assistance from the law librarians who work there. [1] [2] [3]

- In addition to print resources, the public law library also may have subscriptions to legal research databases and search engines, which typically allow you to conduct case law research more efficiently.

- Major online research databases include Westlaw, Lexis, and Bloomberg Law. Through these databases you should be able to find most of the published opinions for federal and state appellate courts. These databases are only available with a subscription, but the library you visit may have one so patrons can conduct research.

- There also are several online databases that can be searched for free, such as Findlaw and Google Scholar. These databases typically have more limited offerings than the subscription databases, and their search engines may be clunkier and less intuitive.

- You can work with many of these free online resources on your computer at home, but you won't have the benefit of a law librarian to help you if you get stuck.

-

2Consider starting with secondary sources. Particularly if you aren't well versed in the legal issues you've identified, a secondary source such as a legal treatise or a law review article can help you focus your research on cases most likely to support your argument.

- Secondary sources also can help you become more familiar with legal phrases and terms of art that are frequently mentioned in judicial opinions or other discussions of your research topic.

- For example, you may be researching merchandising agreements, but be unaware that these agreements also are referred to simply as "licensing agreements," since they typically deal with trademarked intellectual property. Including this information in your searches can produce more targeted search results.

-

3Search relevant statutes. If your legal issues concern a particular state or federal law, the annotations of that law can provide you with names and citations of cases that include a court's interpretation of it.

- If your legal issue relates to a particular law, you always should start with the text of the law itself. However, if the law was passed recently, you may be able to find news articles or other information about the law that can aid in your understanding of it.

- Look up the statute in an annotated reporter, and you'll see citations for articles and court cases that discuss that particular law.

- The context of the annotation should give you some idea of why the law was referenced and what was said about it.

-

4Use alternate terms. Since many words or descriptive terms aren't used universally, expanding or narrowing the words you use in your search can help you find related cases that you might not have found otherwise.

- For example, if you're looking for cases involving car accidents, you may want to search using a word like "vehicle" as well. Not only would that word also include trucks and SUVs, but it's a word more likely used in statutes and police reports, which means it's also more likely to show up in court opinions.

- In other situations, you may need a narrower word. For example, searching for intellectual property cases may turn up cases involving copyrights, patents, and trademarks – each of which is subject to different laws and licensing schemes. If you're only interested in copyright infringement cases, you should use the word "copyright" instead of "intellectual property."

-

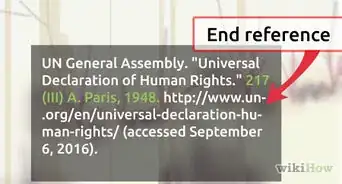

5Identify relevant cases. The major cases related to the legal issues you're researching – those that seem to come up over and over again – can serve as a starting point for your research. Typically these cases establish a significant interpretation that is essential to understanding the issue. [4] [5]

- To locate a case you've found using print volumes, look at the citation. The name of the case will be first.

- After the name of the case, there will be a name surrounded by numbers. The name is the case reporter where that opinion is found.

- The number before the case reporter's name is the volume number, while the number following the reporter's name is the page number where that case is printed within that volume.

- For example, suppose you see the case Smith v. California come up frequently in your reading. The first part of the citation for that case is "Smith v. California, 22 U.S. 248." This tells you that the case is a U.S. Supreme Court case, published in the U.S. Reporter, and that you'll find the case on page 248 of volume 22.

- If you're searching for a case online, you can enter the same information into the search bar of the legal search engine you're using to pull up the case.

- If you don't yet have a citation and you're trying to find cases relevant to an issue, you can use basic search terms online to find cases, but keep in mind there's no guarantee that these cases will actually have value for you.

- If you search using key words, you'll have to read the cases you find to know if they actually have anything to do with the topic or issue you're researching. Even though they're not officially part of the court's decision, the summary and head notes can be helpful here by enabling you to quickly skim and determine if a case has enough relevance to your issue to justify reading further.

- Keep the hierarchy of courts in mind. A U.S. Supreme Court case is binding on all lower courts, but an appellate court decision is only binding within its own district. Outside of that territory, these cases are referred to as "persuasive" authority, meaning a court in another district may consider them is not bound to follow them.

- The strongest case you can find to support your argument is one with facts similar to yours that is binding over the courts in the geographic area where your case will be heard. Make sure the holding itself falls in line with the reasoning of your argument.

Following the Research Trail

-

1Keep track of headnotes. Each case in a reporter begins with a series of numbered paragraphs called "headnotes" that identify and describe particular topics or rules mentioned in the text of the opinion. You can follow the headnotes that relate directly to the issue you're researching to find other cases. [6]

- Keep in mind that the headnotes are created by the editors of the volumes in which the cases are published – they aren't part of the decision itself, but they can help you focus your research.

- Each publisher has its own system for organizing headnotes, so you have to stay within the same publisher when you're following headnotes or the numbers won't match up.

- For example, if you're using West's reporters and you're researching case law on a property line dispute you have with your neighbor, you might look under the West key number 15, which corresponds to "adjoining landowners."

- Most print publishers also have their own online case research services, so be careful not to get confused if you're using more than one online service.

- For example, the publisher West also operates Westlaw, so the key numbers there are the same as the ones in West's print reporters, but wouldn't match up with the headnotes used by another publisher – either online or in print.

- Consider the information in the headnotes to be research assistance, but always read the entire opinion if you think you're going to use it for your argument. The headnotes can sometimes misrepresent the holding of the case, and courts don't consider them authoritative anyway.

-

2Shepardize your case. The term "Shepardize" comes from the title of the Shepard's Citations volumes, books which list cases decided by a given court along with cross references to every other case that cites that case, and why.

- Keep in mind that Shepard's is a particular citator service, which is owned by Lexis. Competing legal publishers such as Bloomberg Law and West have their own citator services that go by different names, but follow the same basic process and lead to similar results.

- Technically, you'll want to Shepardize any case you plan to use or reference in legal documents to make sure it's still "good law." This means the case is still cited by other courts for that rule or principal, and hasn't been overturned by a later court.

- When you Shepardize a case, you look it up in the appropriate volume of Shepard's Citations, and evaluate the stream of cites listed for your case.

- If you're using an online database, it typically will have a method to Shepardize the case that will provide you with the same information as if you'd used the print volumes. An online database also often includes a summary of the results that will tell you more immediately if the case is still considered good law.

-

3Pay attention to signals. Shepard's Citations includes signals that provide information regarding how each citation is related to the initial case you looked up. These signals can help you determine whether the case you've found is still good law.

- Looking up a case using a citator service helps you ascertain the status of the case and its precedential value –whether it is binding on other courts, and to what extent. You do this by finding out what happened to the case after the decision you found, and how other courts treated the decision once it was published.

- For example, if you're reading a case from a federal circuit court of appeals, that case won't have any information on what happened to it afterward. If the losing party appealed to a higher court, and that higher court reversed the lower court decision you read, the case you read is not good law.

- However, if the lower court ruling was affirmed on appeal, it's potentially a stronger case. You'll have to read the higher court case to determine if the reasoning was the same.

- In the line of citations, look for words or codes used as signals to tell you how the case was treated in the citations that follow. For example, you might see the word (or abbreviation for the word) "criticized," followed by a citation to another case. This tells you that the court in the cited case criticized the holding of the case you read.

- If you see any negative treatment of a case you plan to use, you need to read those cases to figure out how they affect your case. If an opinion is roundly criticized by other courts and is never followed, it typically isn't a strong case to cite for that legal principal.

-

4Filter through related cases. Once you've found other cases, read through them to learn the state of the law and court interpretation for the issue you're researching. Those cases may in turn lead you to other cases that could be important to your argument.

- It is always best to cite published cases. A judge may order a case unpublished for a variety of reasons, but in many cases an unpublished opinion is not seen as binding authority.

- If you find an unpublished opinion that you want to cite, check the local rules of the court that issued the opinion to try to figure out why it wasn't published.

- Whenever you find a case that you think you want to use, you must go through the same process you did with the first cases you found, in terms of running the citation of the case through a citator service and confirming that it is still good law.

References

- ↑ http://guides.ll.georgetown.edu/cases

- ↑ http://guides.ll.georgetown.edu/cases/lexis-westlaw

- ↑ http://blogs.loc.gov/law/2013/02/how-to-locate-free-case-law-on-the-internet/

- ↑ http://guides.ll.georgetown.edu/cases

- ↑ https://www.law.georgetown.edu/library/research/tutorials/cases/upload/3_finding_text.pdf

- ↑ https://www.law.georgetown.edu/library/research/tutorials/cases/upload/4_headnotes_text.pdf

-Step-13-Version-3.webp)

-Step-13.webp)

-Step-9-Version-2.webp)