This article was co-authored by Clinton M. Sandvick, JD, PhD. Clinton M. Sandvick worked as a civil litigator in California for over 7 years. He received his JD from the University of Wisconsin-Madison in 1998 and his PhD in American History from the University of Oregon in 2013.

This article has been viewed 112,026 times.

International legal scholars often use the terms “hard” and “soft” to describe certain international laws. If you're trying to understand international law, whether for school or because you want to better understand global events, it can be difficult to distinguish between hard law and soft law. As a further complication, since international law rests on the concept of the sovereignty of independent nation-states, no multinational agreement is either completely hard or completely soft. If you read the terms of a treaty or other international agreement, certain key elements can help you determine the degree of hardness or softness. Recognizing those elements helps you better understand how international law controls the actions of countries and their relations with each other.

Steps

Pinpointing Legal Obligations

-

1Identify the type of document or agreement. One simplistic distinction between soft law and hard law states that hard law is legally binding, while soft law is not. This distinction can lead scholars into a semantic debate over whether any agreement that isn’t legally binding can rightfully be called a law. Nonetheless, some types of agreements are automatically considered hard law.[1]

- Treaties are a prime example of an agreement traditionally considered hard law by default. When countries ratify a treaty, if they have national laws that contradict the treaty, they are obligated to change those laws to comport with the treaty.

- The U.S. considers treaties legally binding both internationally and domestically. After the Senate ratifies a treaty, Congress passes any federal law necessary to comply with its terms.[2]

- UN Security Council resolutions legally bind all UN members under the power vested in the Council under Article 25 of the UN Charter. [3]

-

2Determine the degree to which the agreement is legally binding. A high level of legal obligation indicates an international agreement probably is a harder law, depending on other factors.

- Since international contracts advance the interests of the countries that sign them, those countries may have little motivation to breach the contract. In recognition of that fact, the agreement itself may not have much language indicating its legally binding nature.

- Sometimes treaties that deal with human rights or other normative principles are called “covenants.” These agreements typically are legally binding to the same extent as treaties, although they may lack centrally enforced legal obligations.[4]

- A country may sign a treaty, but lodge a formal reservation to certain provisions. The reservation decreases that country’s legal obligation in relation to the specific provision with which it disagrees.[5]

- International agreements that are not considered legally binding at all are soft law. Often these agreements contain conditions or escape clauses that allow the countries signing them to declare a common commitment to certain principles while retaining their own sovereignty and independence.[6]

Advertisement -

3Recognize when non-binding agreements still shape countries’ behavior and relations. Regardless of whether an international agreement is legally binding, if a large number of countries are on board with its principles, they may exert political pressure on other countries to comply.

- Some international law may be legally binding on some countries but not others. For example, a decision handed down by the European Court of Human Rights is only legally binding on the countries involved in that particular case. However, that same decision may help sway the opinion of another court or international organization faced with a similar case.[7]

- Soft law may set forth broad principles on which there is multinational agreement, although the countries disagree on the particulars. These softer agreements can serve as the foundation for harder agreements in the future.[8]

- A country that agrees with a treaty in principle, but cannot complete the ratification process, may nevertheless adopt domestic legislation that complies with the overall thrust of the treaty.

Analyzing the Language

-

1Look for detailed and precise language. Generally, a harder law will have a high degree of precision, while a softer law will use more vague generalities or appeals to ideals and broad moral or ethical principles.

- Describing commitments in precise terms ensures participating countries understand the limits of their obligations, and prevents self-serving or opportunistic behavior in the future.

- Harder laws also use precise language in outlining conditions or exceptions to obligations. This helps avoid the possibility that one country could take advantage of a loophole to undermine the purpose of the agreement.

-

2Distinguish words that create duties from those that describe ideals. Verbs such as “will” or “must” tell you someone is being required to do something, while verbs such as “may” or “can” tell you someone is allowed to do something.

- Harder laws include demands or obligations with which participating countries must comply. Typically the agreement applies sanctions or other punishment to countries that don’t fulfill their obligations under the agreement by a certain date.

- In contrast, softer laws typically list a number of things participating countries are permitted to do within the confines of the agreement, but do not require them to do anything in particular.

- If the agreement includes promises from participating countries to investigate an issue or conduct feasibility studies within a period of time, but does not require the implementation of any concrete measures, these are soft law provisions.

-

3Locate key terms and how the agreement defines them. International law documents use operative language that diplomats, heads of state, and other government or industry leaders will have to interpret. The length and specificity of definitions are crucial to determining the relative hardness or softness of the law.

- Softer laws leave broad terms open to interpretation, while harder laws contain extensive descriptions of what is being regulated. An example of a lengthy description in hard law can be found in the European Union’s directive defining allowable ingredients in fruit jams, jellies and similar spreads, which runs 12 pages.[9]

- Not all hard laws have such detailed definitions. For example, the European Convention on Human Rights leaves a number of key terms, such as what constitutes "inhuman and degrading treatment" open to interpretation. This allows a degree of flexibility in dealing with situations national leaders couldn't have contemplated when they drafted the agreement.[10]

- Defining a term as narrowly as possible limits the ability of countries to argue for a self-serving interpretation in the future, and eliminates gray areas. However, countries may construct a softer law with the full intention of allowing differing interpretations to coexist as long as they all agree on the same overall concept.

Understanding Interpretation and Enforcement

-

1Identify who is responsible for interpreting the agreement. Harder laws typically delegate the authority for interpretation of the agreement to an independent third body, while softer laws leave interpretation up to participating countries.

- Independent bodies that produce binding interpretation and settlement of disputes are most common in international organizations, and their decisions are binding on member countries. For example, the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea resolves disputes between countries under the 1982 Convention on the Law of the Sea.

- Often, decisions of these international courts are only binding on the parties involved in that particular dispute. [11]

-

2Determine what enforcement mechanisms are included in the agreement. Because of the complex interplay between international law and state sovereignty, even the hardest laws often are lacking in strong enforcement provisions.

- Under the UN Charter, countries can seek authorization from the Security Council to enforce international agreements using collective armed force. This is the strongest enforcement mechanism available in international law.

- Realist legal scholars point to the lack of enforcement measures in international law to argue that all international law is inherently soft.

-

3Note whether the agreement creates or uses an independent international organization.

- International governing bodies such as the European Union tend to have the strongest enforcement powers. The EU also has its own government institutions.

- Harder laws often establish their own institutions to interpret and enforce the agreement. For example, the European Convention on Human Rights is interpreted and enforced by the European Court of Human Rights.[12]

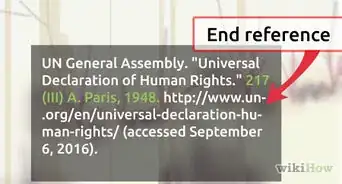

References

- ↑ http://scholarship.law.gwu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2048&context=faculty_publications

- ↑ https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/RL32528.pdf

- ↑ http://scholarship.law.gwu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2048&context=faculty_publications

- ↑ http://www.researchgate.net/profile/Duncan_Snidal2/publication/4770665_Hard_and_Soft_Law_in_International_Governance/links/541481e60cf2bb7347db3234.pdf

- ↑ http://www.legalanswers.sl.nsw.gov.au/hot_topics/pdf/international_69.pdf

- ↑ https://clg.portalxm.com/library/keytext.cfm?keytext_id=68

- ↑ http://scholarship.law.gwu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2048&context=faculty_publications

- ↑ http://www.legalanswers.sl.nsw.gov.au/hot_topics/pdf/international_69.pdf

- ↑ http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:02001L0113-20131118&from=EN

- ↑ http://www.researchgate.net/profile/Duncan_Snidal2/publication/4770665_Hard_and_Soft_Law_in_International_Governance/links/541481e60cf2bb7347db3234.pdf

- ↑ http://www.legalanswers.sl.nsw.gov.au/hot_topics/pdf/international_69.pdf

- ↑ http://www.researchgate.net/profile/Duncan_Snidal2/publication/4770665_Hard_and_Soft_Law_in_International_Governance/links/541481e60cf2bb7347db3234.pdf

-Step-1-Version-3.webp)

-Step-2-Version-3.webp)

-Step-3-Version-3.webp)

-Step-4-Version-3.webp)

-Step-5-Version-3.webp)

-Step-6-Version-2.webp)

-Step-7-Version-2.webp)

-Step-8-Version-2.webp)

-Step-9-Version-2.webp)

-Step-13-Version-3.webp)

-Step-13.webp)