This article was co-authored by Melessa Sargent. Melessa Sargent is the President of Scriptwriters Network, a non-profit organization that brings in entertainment professionals to teach the art and business of script writing for TV, features and new media. The Network serves its members by providing educational programming, developing access and opportunity through alliances with industry professionals, and furthering the cause and quality of writing in the entertainment industry. Under Melessa's leadership, SWN has won numbers awards including the Los Angeles Award from 2014 through 2021, and the Innovation & Excellence award in 2020.

This article has been viewed 40,561 times.

Teleplays or screenwriting for TV shows is a detailed process. Before writing, research shows and scripts, and write an outline of your screenplay. The number of acts your teleplay contains depends on the duration of your show, for example, an hour or 30-minute show. However, always try to stick to a three-act minimum. Develop your script by beginning with a teaser, and then present your characters and the main conflict. Try to end each act with a cliffhanger that will make your audience want to keep watching. When writing your teleplay, make sure the formatting follows the general guidelines for scriptwriting, as well.

Steps

Structuring the Teleplay

-

1Do your research. Before writing your own teleplay, sit down and watch or re-watch award-winning or acclaimed television shows, particularly the kinds of shows you want to write for.[1] Use a pen and paper or a computer to take notes. Take notes on the structure and style of the show, how many lines each characters’ dialogue has, and the length of each act and the script as a whole.[2]

- Pay close attention to the alignment of commercial breaks with scene breaks.

- In addition to watching TV shows, study old scripts, especially the scripts of the types of shows you want to write for.

-

2Write an outline. Start with a short description of the show. For example, “Henry, an average high school student living in Los Angeles, wakes up to find himself abducted by aliens.” Then, create a detailed outline that describes the teaser, as well as the acts.[3]Advertisement

-

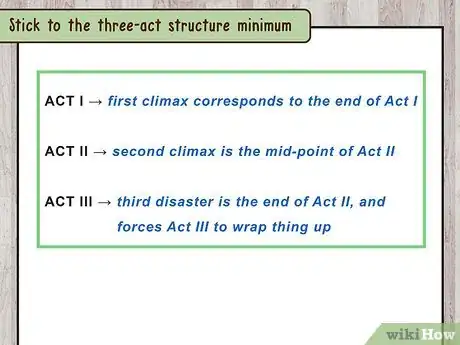

3Stick to the three-act structure minimum. A one-hour TV show typically consists of a teaser and four acts. However, sometimes it consists of more acts, for example five acts. On the other hand, 30-minute sitcoms typically contain three acts. Therefore, the number of acts your show has usually depends on the show’s length.[4]

- A teleplay for a one-hour TV show is typically 59 to 66 pages long.

Developing the Acts

-

1Develop the teaser. Teasers are one to five-minute mini-acts at the beginning of the show. They often occur before the opening credits. Teasers are typically used to set-up the episode and catch the audience’s attention. Introduce the main character, their world, and the conflict.[5]

- In the teaser, you should Introduce the conflict by depicting the main character in peril, or confronted with a problem. For example, the teaser could consist of a scene where Henry, who has been abducted by aliens, is lying in a laboratory with bright lights and strapped to a medical bed. He could begin to say something like, "Where am I?" This could be followed by an unknown being putting a gas mask on his face, making Henry fall unconscious.

- Teasers are typically two to three pages but can be as many as five pages.

-

2Write act one. In act one you will need to set the stage. Describe the setting, i.e., where the characters are, and what year and time of day it is. Provide more detailed backgrounds for the main characters and other characters in the story, i.e., sub-plots. Set-up an immediate goal for your main character. By the end of the act, your main character should either reach or fail to reach the immediate goal.[6]

- For example, act one could be a flashback to 24 hours before Henry is abducted. In the scene, describe who Henry is and his life leading up to the moment before he is abducted. Describe the flashback as a peaceful, happy place. A stark contrast to Henry's new reality.

- Act one needs to lead up to act two. Therefore, end act one with a cliffhanger or hook, i.e., a strong dramatic moment.

- Each act is typically 14 to 15 pages or 10 minutes long. Each page should follow the general rule of thumb of one page per minute.[7]

-

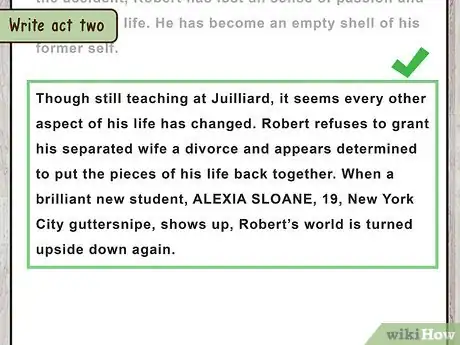

3Write act two. Raise the stakes in act two by having your character struggle with the conflict. Your main character should be dealing with the conflict, i.e., trying to find a solution. At the beginning of the act, they should have some hope that they will succeed in dealing with the conflict. However, end the scene with another cliffhanger.[8]

- The cliffhanger should trivialize the character’s solution or strategy forcing them to face the fact that they might not succeed. It should introduce another conflict.

- For example, in act two, the flashback could turn into a nightmare before he begins to wake up again. Before Henry regains conscious, he might hear voices speaking in a language he has never heard before. You could describe other smells, sounds, and textures that are unfamiliar. He might even hear a familiar scream of someone nearby.

-

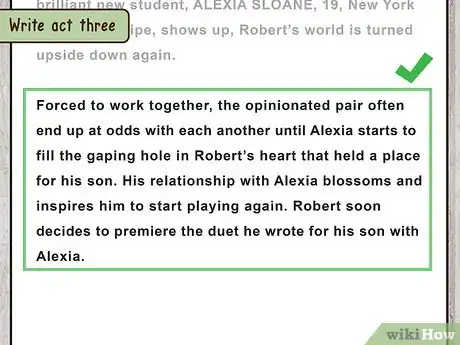

4Write act three. In act three, your main character is at their lowest point. In other words, the conflict is winning or getting the best of your character. For example, the hope that your character had in act two is proven to be false.[9]

- By the end of this act, your audience should want to continue watching to see how your character will prevail against such odds.

- For example, once Henry has regained full conscious he realizes he has been abducted. Then, he realizes that his girlfriend has been abducted, as well. Perhaps the alien beings are preparing to operate on his girlfriend or run lab tests on her. Your main character feels powerless because he cannot do anything to protect his beloved girlfriend.

-

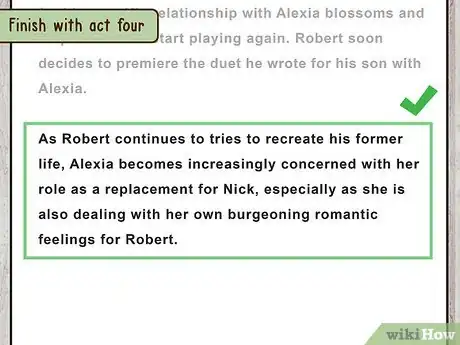

5Finish with act four. In act four, your main character, against all odds, should begin to prevail again. By learning from their mistakes in the second and third act, they are able to find a better solution to the conflict. By the end of this act, your main character should begin to triumph and ultimately win.[10]

- For example, Henry is at his lowest point and about to give up when a math formula he learned in calculus the day before flashes across his mind. He realizes that the solution to the formula will free him and his girlfriend. While the aliens are preparing to operate, he inputs the solution into a computer system nearby. It turns out that the solution is the key to shutting down the alien's system. He frees himself and his girlfriend, and together they jump into a capsule that will teleport them back to earth.

- Alternatively, you can end the fourth act with another cliffhanger, which will set up the next episode or a final act five.

- If you are only writing three acts, then combine act two and act three into act two, and make the fourth act the final act three.

Formatting the Teleplay

-

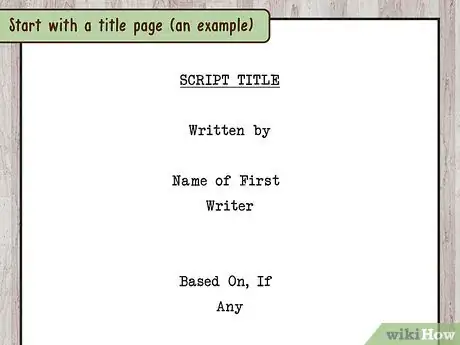

1Start with a title page. Every script needs to have a title page with one contact address. The title should be centered and closed in quotation marks. Underneath the title write “written by”, hit enter, then write your name. Place your contact address in the bottom left-hand corner.[11]

- The contact address should include your name, email, and phone number. If you have an agent, their contact address should go in the bottom right-hand corner.

- Above the title it should also say in all caps: SCREENPLAY FORMAT FOR TV SHOWS. This should be underlined, as well.

-

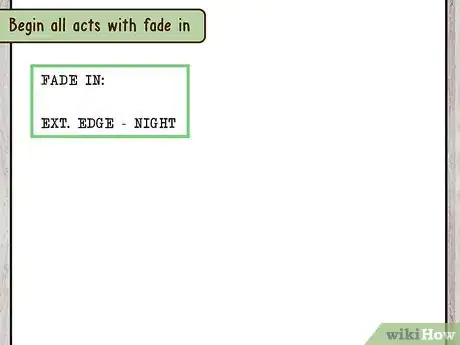

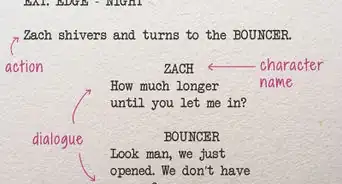

2Begin all acts with fade in. Capitalize “Fade in” and follow it with a colon. “FADE IN” also needs to be followed by a scene heading. Capitalize all scene headings, as well. Your scene heading must also indicate interior or exterior, the location, and time of day. Abbreviate interior and exterior with “INT.” and “EXT.”[12]

- For example, INT. LOS ANGELES – 10 A.M.

-

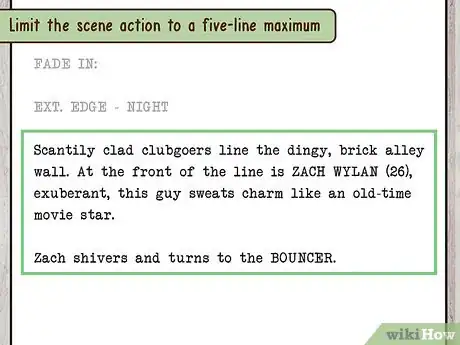

3Limit the scene action to a five-line maximum. Double-spaced underneath the scene heading is the scene action in upper and lower case letters. If there are paragraphs in your scene action, they need to be separated with double-spaces, as well.[13]

- Scene action should only outline what is happening on the screen, and be kept at a five-line maximum, for example, “Deborah enters the café.”

- Always follow a scene heading with a line of scene action.

-

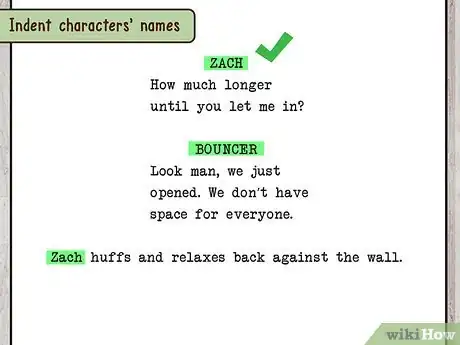

4Indent characters’ names. Following the scene action, you can begin the characters’ dialogue. Indent the characters’ names to the middle of the page, but do not center it. The characters’ names should appear above the dialogue in all caps, for example, “TINA.” Designate the character with either their first or last name.[14]

- Alternatively, you can designate a character with a role, for example, “DOCTOR.” However, whatever you use to designate a character should be used consistently throughout the script.

- Dialogue appears in regular text and it is not centered, either.

-

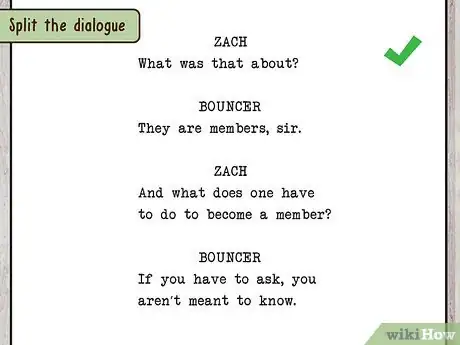

5Split the dialogue. If a character’s dialogue continues to run onto the next page, only split the dialogue if at least two lines appear on the previous page. Only split the dialogue after a sentence, as well. State, “CONT’D” in parenthesis after the character’s name if the dialogue is split.[15]

- If there are instructions like pause, smile, or clap, then write the instructions in parenthesis and in lowercase letters in the body of the dialogue, for example, (smile). Never leave a parenthetical hanging at the end of a page.

-

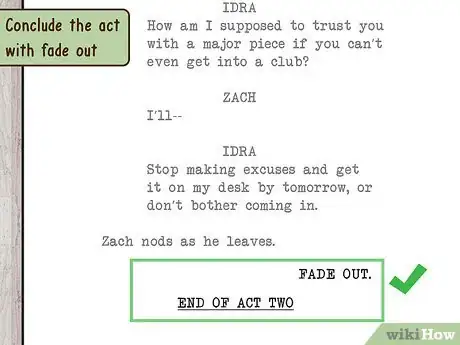

6Conclude the act with fade out. Always conclude the act or teaser with a “FADE OUT.” Fade out must be capitalized and followed by a period. Double-spaced and centered below “FADE OUT,” write, “END OF TEASER (or ACT ONE),” in all caps and underline it.[16]

- For example: END OF TEASER.

- You do not need to indicate where the commercial breaks will go when formatting and writing your teleplay. However, keep in mind the length of ad breaks so you can adjust the length of your teleplay accordingly.

References

- ↑ Melessa Sargent. Professional Writer. Expert Interview. 14 August 2019.

- ↑ http://www.steves-digicams.com/knowledge-center/how-tos/filmmaking-tips/screenwriting-how-to-write-an-hour-episodic-tv-show.html

- ↑ http://www.writersdigest.com/online-editor/tv-writing-101-how-not-to-write-a-boring-script

- ↑ http://www.movieoutline.com/articles/television-script-format.html

- ↑ https://screencraft.org/2016/01/05/the-screenwriters-guide-to-formatting-television-scripts/

- ↑ https://screencraft.org/2016/01/05/the-screenwriters-guide-to-formatting-television-scripts/

- ↑ http://www.movieoutline.com/articles/television-script-format.html

- ↑ https://screencraft.org/2016/01/05/the-screenwriters-guide-to-formatting-television-scripts/

- ↑ https://screencraft.org/2016/01/05/the-screenwriters-guide-to-formatting-television-scripts/

- ↑ https://screencraft.org/2016/01/05/the-screenwriters-guide-to-formatting-television-scripts/

- ↑ https://downloads.bbc.co.uk/writersroom/scripts/screenplaytv.pdf

- ↑ https://downloads.bbc.co.uk/writersroom/scripts/screenplaytv.pdf

- ↑ https://downloads.bbc.co.uk/writersroom/scripts/screenplaytv.pdf

- ↑ https://downloads.bbc.co.uk/writersroom/scripts/screenplaytv.pdf

- ↑ https://downloads.bbc.co.uk/writersroom/scripts/screenplaytv.pdf

- ↑ https://downloads.bbc.co.uk/writersroom/scripts/screenplaytv.pdf