This article was co-authored by Laura Marusinec, MD. Dr. Marusinec is a board certified Pediatrician at the Children's Hospital of Wisconsin, where she is on the Clinical Practice Council. She received her M.D. from the Medical College of Wisconsin School of Medicine in 1995 and completed her residency at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Pediatrics in 1998. She is a member of the American Medical Writers Association and the Society for Pediatric Urgent Care.

There are 8 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page.

wikiHow marks an article as reader-approved once it receives enough positive feedback. This article received 16 testimonials and 100% of readers who voted found it helpful, earning it our reader-approved status.

This article has been viewed 716,748 times.

As you travel to higher altitudes, such as the areas around mountains, many changes are observed in the environment that can affect you. These include cold, low humidity, increased UV radiation from the sun, decreased air pressure, and reduced oxygen saturation. Altitude sickness is our body's response to the low air pressure and oxygen typically occurring at altitudes over 8,000 ft.[1] If you know that you are going to be traveling to high altitudes, follow a few simple steps to prevent altitude sickness.

Steps

Preventing Altitude Sickness

-

1Ascend slowly. When you are traveling to places in high altitudes, you should try to get there slowly. Your body typically needs three to five days at altitudes above 8,000 feet to acclimate it to the environment before traveling higher. To help with this, especially if you are traveling where there are no altitude markers, purchase an altimeter or a watch with altitude meter in order to know how high you have traveled. You can buy these online or from a mountain sport shop.

- There are some other behaviors you should avoid. Do not go over 9,000 feet in altitude in 1 day. Do not sleep 1,000 to 2,000 feet above the altitude you slept at the previous night. You should always spend an extra day acclimating for every 3,300 ft.[2]

-

2Get rest. Another way to combat altitude sickness is to get plenty of rest. Domestic and international travel can alter normal sleep patterns. This can cause you to become tired and dehydrated, which increases your risk for altitude sickness. Before starting your ascent, plan a day or two of rest to get used to your new environment and sleep patterns, especially if you are traveling internationally.

- In addition, during your three to five day acclimation to your new altitude, take the first day or two to rest before exploring the area.

Advertisement -

3Take prophylaxis medications. Before you go on a journey where you will ascend to high altitudes, get some medication to help. Schedule an appointment with your doctor to get prophylaxis medications before you leave. Discuss your past medical history and explain that you are going up to elevations greater than 8,000 to 9,000 ft. If you're not allergic, a prescription for acetazolamide may be given to you by your doctor.

- This is an FDA approved drug for the prevention and treatment of acute mountain sickness. Acetazolamide is a diuretic, which increases urine production, and is known to cause an increase in respiratory ventilation that allows more oxygen exchange in our body.

- Take 125 mg as prescribed twice daily starting one day before your trip and take for two days at your highest altitude..[3]

-

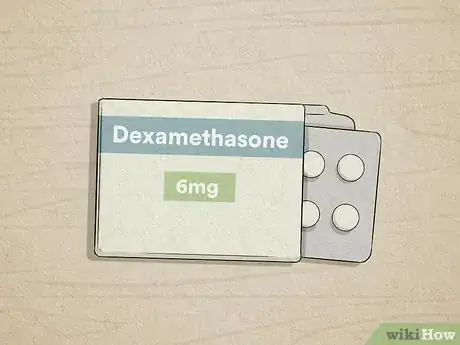

4Try dexamethasone. If your doctor advises against acetazolamide or you are allergic, there are other options. You can take other non-FDA approved medications such as dexamethasone, which is a steroid. Studies have shown that the drug reduces the incidence and severity of acute mountain sickness.

- Take this medication as prescribed, which is usually 4 mg every 6 to 12 hours starting the day before your trip and continue until you are fully acclimated at your highest altitude.

- 600mg of ibuprofen every 8 hours may also help prevent acute mountain sickness.

- Ginkgo biloba has been studied for treatment and prevention of altitude sickness, but the results are varied and not recommended for use.[4]

-

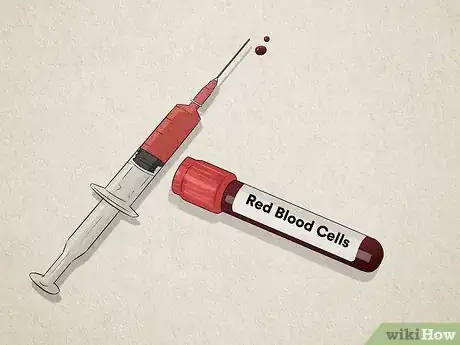

5Test your red blood cells (RBC). Before you leave on your trip, you may need to have your RBCs tested. Schedule an appointment with your doctor for this test before you leave. If you are found to have anemia or low red blood cells, your doctor may advise you to correct this before going on your trip. This is important because RBCs carry oxygen to your tissues and organs and are needed for survival.

- There are many reasons for low RBC, the most common is iron deficiency. B vitamin deficiency can also lead to low red blood cells. If low, your doctor may advise you to take iron or vitamin B supplements to correct your RBC.[5]

-

6Drink plenty of water. Dehydration reduces your body’s ability to acclimate to new altitudes. Drink two to three liters daily starting the day before your trip. Keep an extra liter of water on you during your ascent. Make sure you drink as needed on your way down.

- Do not drink any alcohol and avoid it for the first 48 hours of your trip. Alcohol is a depressant and can slow down your breathing rate and cause dehydration.

- You should also avoid caffeinated products, such as energy drinks and sodas. Caffeine can lead to the dehydration of your muscles.

-

7Eat appropriately. There are certain kinds of foods that you should eat to get ready for your trip and prevent altitude sickness. High carbohydrate diets have shown in some studies to alleviate acute mountain sickness symptoms as well as improve mood and performance.[6] Other studies have shown improved oxygen saturation in the blood during simulated high altitude experiments from the carbohydrates as well.[7] It is believed that carbohydrate diets can improve energy balance. Eat a high carbohydrate diet before and during the acclimation periods.

- This can include pastas, breads, fruits, and potato based meals.

- In addition, excess salt should be avoided. Too much salt will cause the dehydration of your body’s tissues. Look for food and meals labeled with low salt or no salt added at the supermarket.

- Physical endurance and conditioning may appear to be a good idea before mountain climbing. However, studies have shown there is no evidence that physical fitness protects against altitude sickness.[8] [9]

Recognizing the Symptoms

-

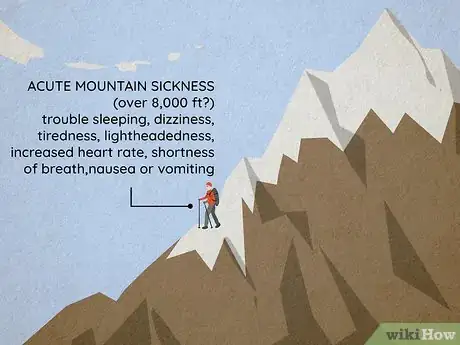

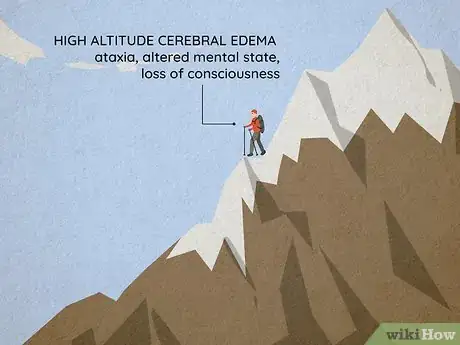

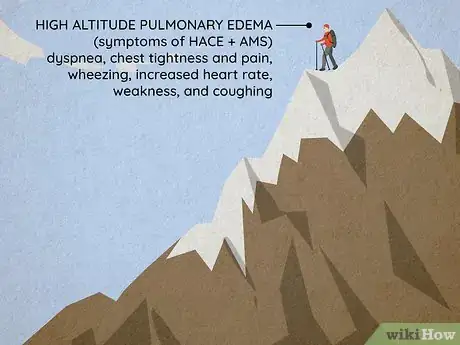

1Learn the different types. There are 3 types of syndromes that comprise altitude sickness: acute mountain sickness, high altitude cerebral edema (HACE), and altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE).

- Acute mountain sickness is due to reduced air pressure and oxygen.

- High altitude cerebral edema (HACE) is a severe progression of acute mountain sickness caused by brain swelling and the leaking of dilated brain vessels.

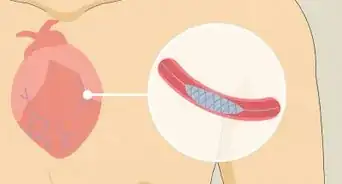

- High altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE) can occur with HACE, on its own after acute mountain sickness, or develop one to four days after traveling above 8,000 ft. This is caused by swelling in the lungs due to fluid leakage into the lungs caused by high pressure and constriction of blood vessels in the lungs. [10]

-

2Recognize acute mountain sickness. Acute mountain sickness is a relatively common disease in certain parts of the world. It affects 25% of travelers over 8,000 ft in Colorado, 50% percent of travelers in the Himalayas, and 85 % of those in the Mount Everest region. There are many symptoms of acute mountain sickness.

- These include a headache within two to 12 hours of new altitude, trouble falling or staying asleep, dizziness, tiredness, lightheadedness, increased heart rate, shortness of breath during movement, and nausea or vomiting.[11]

-

3Notice high altitude cerebral edema (HACE). Since HACE is a severe extension of acute mountain sickness, you will start with those symptoms first. As the condition escalates, you will contract other symptoms. These include ataxia, which is the inability to walk straight, or the tendency to wobble when walking or walking diagonally. You may also suffer from an altered mental state, which can manifest as drowsiness, confusion, and changes in your speech, memory, mobility, thoughts, and attention span.

- You may also lose consciousness or go into a coma.

- Unlike acute mountain sickness, HACE is rather rare. It only affects from .1% to 4% of people.[12]

-

4Watch out for high altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE). Since this can be an escalation of HACE, you may experience the symptoms of acute mountain sickness and HACE as well. Since it can come up on its own, however, you should watch out for the symptoms as a standalone condition. You may experience dyspnea, which a shortness of breath at rest. You also may feel chest tightness and pain, wheezing breath on the exhalation from your lungs, increased breathing and heart rate, weakness, and coughing.

- You may also notice a physical change as well, such as cyanosis, which is a condition where your mouth and fingers turn darker or bluish in color.

- Like with HACE, HAPE is relatively rare, with incidences from .1% to 4%.[13]

-

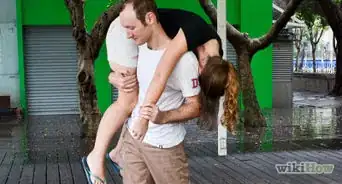

5Deal with symptoms. Even if you try to prevent altitude sickness, it may still happen. If this is the case, you should be careful not to make it worse. If you have acute mountain sickness, wait up to 12 hours for symptom improvement. Try also to descend immediately at least down 1,000 feet if symptoms do not improve in 12 hours or sooner if your symptoms are severe. If you are unable to descend, treatment with oxygen should help your symptoms within a few hours if it is available.. At this point, reassess symptoms for improvement.

- If you are dealing with signs or symptoms of HACE or HAPE, descend immediately with as little exertion as possible so as not to aggravate the symptoms. You should then reassess symptoms for improvement periodically.

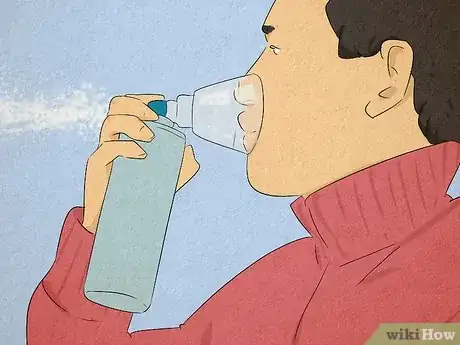

- If descent is not possible because of weather conditions or other reasons, administer oxygen to increase oxygen pressure. Place the mask on yourself and the tube of the mask in the tank nozzle. Release the oxygen. You can also be placed in a portable hyperbaric chamber. If these are available, then descent may not be needed if the symptoms are not severe and you respond to treatment. These are lightweight machines usually carried by rescue teams or at rescue stations. If radio or phone is available, report incidences to the rescue team and give them your location and wait for arrival. [14]

-

6Take emergency drugs. There are some medications that may be given to you on an emergency basis by your doctor. For acute mountain sickness treatment, you may be given acetazolamide or dexamethasone. For HACE treatment, you may be given dexamethasone. Take pills immediately and swallow with water.

- Your doctor may also prescribe you emergency drugs in case of HAPE, which are non-FDA approved drugs for prophylaxis and HAPE treatment. Small studies have shown some drugs reduce the incidence of HAPE if taken 24 hours before your trip. These include nifedipine (Procardia), salmeterol (Serevent), phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors (tadalafil, Cialis), and sildenafil (Viagra).[15]

Foods to Eat and Avoid

Expert Q&A

-

QuestionWhat precautions should I take if I have asthma?

Janice Litza, MDDr. Litza is a board certified Family Medicine Physician in Wisconsin. She is a practicing Physician and taught as a Clinical Professor for 13 years, after receiving her MD from the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Medicine and Public Health in 1998.

Janice Litza, MDDr. Litza is a board certified Family Medicine Physician in Wisconsin. She is a practicing Physician and taught as a Clinical Professor for 13 years, after receiving her MD from the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Medicine and Public Health in 1998.

Board Certified Family Medicine Physician People with any chronic lung conditions should avoid high altitude hikes unless they have been evaluated by a lung specialist and have the recommended equipment, because they are at high risk for more severe altitude sickness.

People with any chronic lung conditions should avoid high altitude hikes unless they have been evaluated by a lung specialist and have the recommended equipment, because they are at high risk for more severe altitude sickness.

Warnings

- If you are feeling symptoms of altitude illness, don't continue to ascend, especially to sleep.⧼thumbs_response⧽

- Descend if your symptoms are increasing or not going away while resting.⧼thumbs_response⧽

- If you have certain ailments, you may experience worsening of your condition at high altitudes. You may also need a pre-trip workup by your healthcare provider to assure safety. These include arrhythmias, severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), severe congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, hypertension, pulmonary hypertension, diabetes, and sickle cell disease. You are also at risk of getting sick if you are on narcotic pain medications, which cause the respiration rate to go down.⧼thumbs_response⧽

- Pregnant women should not sleep at altitudes higher than 12,000 feet.⧼thumbs_response⧽

References

- ↑ Hackett P, Shlim D. Altitude Illness. Chapter 2 Pre-travel consultation. CDC. Aug 1st, 2013. http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2014/chapter-2-the-pre-travel-consultation/altitude-illness

- ↑ Hackett P, Shlim D. Altitude Illness. Chapter 2 Pre-travel consultation. CDC. Aug 1st, 2013. http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2014/chapter-2-the-pre-travel-consultation/altitude-illness

- ↑ Ellsworth A.J., Meyer E.F., Larson E. B. Acetazolamide or dexamethasone use versus placebo to prevent acute mountain sickness on Mount Rainier. Western Journal of Medicine. 1991 Mar; 154(3): 289–293.

- ↑ Fiore D, Hall S. Altitude Illness: Risk Factors, Prevention, Presentation, and Treatment. American Family Physician journal. 2010 Nov 1;82(9):1103-1110.

- ↑ Fiore D, Hall S. Altitude Illness: Risk Factors, Prevention, Presentation, and Treatment. American Family Physician journal. 2010 Nov 1;82(9):1103-1110.

- ↑ Poos MI, Costello R, Carlson-Newberry SJ. Committee on Military Nutrition Research: Activity Report: National Academies Press (US). December 1, 1994 through May 31, 1999.

- ↑ Lawless NP. et al. Improvement in hypoxemia at 4600 meters of simulated altitude with carbohydrate ingestion. Aviation, Space, and Environmental medicine journal. 1999 Sep;70(9):874-8.

- ↑ http://www.theuiaa.org/faq-mountaineering.html

- ↑ Honigman B. et al. Sea-level physical activity and acute mountain sickness at moderate altitude. Western Journal Medicine. 1995 Aug;163(2):117-21.

- ↑ Fiore D, Hall S. Altitude Illness: Risk Factors, Prevention, Presentation, and Treatment. American Family Physician journal. 2010 Nov 1;82(9):1103-1110.

- ↑ Fiore D, Hall S. Altitude Illness: Risk Factors, Prevention, Presentation, and Treatment. American Family Physician journal. 2010 Nov 1;82(9):1103-1110.

- ↑ Fiore D, Hall S. Altitude Illness: Risk Factors, Prevention, Presentation, and Treatment. American Family Physician journal. 2010 Nov 1;82(9):1103-1110.

- ↑ Fiore D, Hall S. Altitude Illness: Risk Factors, Prevention, Presentation, and Treatment. American Family Physician journal. 2010 Nov 1;82(9):1103-1110.

- ↑ Fiore D, Hall S. Altitude Illness: Risk Factors, Prevention, Presentation, and Treatment. American Family Physician journal. 2010 Nov 1;82(9):1103-1110.

- ↑ Fiore D, Hall S. Altitude Illness: Risk Factors, Prevention, Presentation, and Treatment. American Family Physician journal. 2010 Nov 1;82(9):1103-1110.

About This Article

If you want to prevent altitude sickness, try to ascend to higher altitudes as slowly as possible, since you typically need 3-5 days to adjust to heights above 8,000 feet. Do not go above 9,000 feet in altitude in one day. Get plenty of rest and drink 2 to 3 liters of water a day if you’re taking a trip with altitude variations, and consider asking your doctor about prophylaxis medications that can help prevent altitude sickness. A diet high in carbohydrates such as pastas and breads may also help you avoid getting sick. For more tips from our Medical reviewer, including how to recognize the symptoms of altitude sickness, read on!

Medical Disclaimer

The content of this article is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, examination, diagnosis, or treatment. You should always contact your doctor or other qualified healthcare professional before starting, changing, or stopping any kind of health treatment.

Read More...