This article was co-authored by Laura Marusinec, MD. Dr. Marusinec is a board certified Pediatrician at the Children's Hospital of Wisconsin, where she is on the Clinical Practice Council. She received her M.D. from the Medical College of Wisconsin School of Medicine in 1995 and completed her residency at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Pediatrics in 1998. She is a member of the American Medical Writers Association and the Society for Pediatric Urgent Care.

There are 26 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page.

This article has been viewed 169,125 times.

Newborns undergo rapid changes in the first days and weeks of life. Their skin can show a wide range of colors, textures, and marks, many of which will come and go on their own. Some skin conditions can be the sign of something more serious, however. If you have a newborn, you can learn what to expect from your newborn’s skin, and when to contact your medical professionals.

Steps

Recognizing Skin Color

-

1Note your newborn’s skin tone. At birth, a newborn’s skin may be reddish or pinkish.[1] However, the baby’s hands and feet may be bluish (acrocyanosis) because blood and oxygen are not yet circulating fully to the extremities.[2] [3] [4] As the newborn’s circulatory system opens, this bluish color will subside.

-

2Look for common color patches. There may be pink patches over a newborn's eye or in the middle of his or her forehead.[8] These are called Nevus simplex, commonly known as “angel kisses” or “salmon patches.” Usually, these fade within a few months, although they may be faintly visible afterwards.

- Occasionally, a similar patch may be visible on the nape of a newborn’s neck. This is often called a “stork bite” and will also fade or become less noticeable in time.

Advertisement -

3Don’t be alarmed if there is some bruising. Because birth can be a physically demanding experience for both mother and baby, a newborn may have some bruising. This may show as patches of blue or other colors on the baby’s skin at various places. This is not usually a cause for concern, however. Your physician will examine your newborn, including any bruising (if present), and make sure that he or she is ok.

Noting Skin Condition

-

1Watch for swelling. At birth, a newborn’s skin may appear smooth and slightly puffy. There may also be noticeable swelling.[9] Some amount of puffiness, especially on an infant's head or eyes (called edema) is not uncommon and will go away.[10] [11] However, let your physician know if you notice increased swelling after birth, especially in a particular area, such as the newborn’s feet or hands.[12]

-

2Expect some peeling and flaking. 24-36 hours after birth, a newborn’s skin may still be pinkish, but it may also begin to look flaky.[13] [14] There may be some skin peeling (most common in the hands and feet); normally, it will go away without issue.

- Your infant’s skin may still turn reddish when he or she cries, and turn slightly bluish or spotted if he or she becomes cold.[15]

-

3Look for a natural coating on the skin. A newborn’s skin may be covered in vernix caseosa, a white, cheesy substance. This may be present only at skin folds, such as on the legs.[16] This protects the infant’s skin from amniotic fluid when in the womb, and will wash off during his or her first bath.[17] Since the vernix caseosa washes away, you may not notice it for very long, if at all.

-

4Expect some “baby acne.” Mild acne may develop in the first few weeks of an infant’s life. This is caused by the mother’s hormones that were passed to infant. The condition is harmless, and will clear on its own.[18]

-

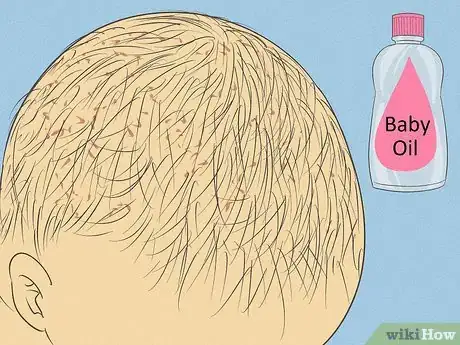

5Care for “cradle cap,” if it appears. Many infants will show “cradle cap” (Seborrheic dermatitis) at some point. The skin on top of the infant’s head will appear dry, flaky, and perhaps oily.[19] [20] Cradle cap is harmless and it will typically go away by the time an infant is one year old. You can care for cradle cap at home:[21]

- Rub the skin of your baby’s head with baby oil, mineral oil, or petroleum jelly an hour before shampooing. This will help to loosen dry and dead skin flakes.

- Wet the baby’s scalp before shampooing, and brush gently with a soft-bristle brush. This well help to remove cradle cap scales.

- Wash and rinse your baby’s scalp, then gently dry it with a towel.

Recognizing Common Skin Variations

-

1Be prepared for body hair. A newborn’s skin may be covered in fine body hair called lanugo. This most commonly shows on the shoulders, back, and sacral area (at the bottom of the spine).[22] This is usually associated with premature infants, but can be present on any.[23] [24] Lanugo will disappear in the infant’s first few weeks of life.

-

2Watch for milia. Plugged pores in the skin of an infant (usually the nose, chin, and cheeks) are called milia.[25] [26] These spots may appear similar to small whiteheads; however, they should not be confused with common “baby acne.” Milia is a common condition, appearing in about 40% of newborns, and will disappear on its own.

-

3

-

4

-

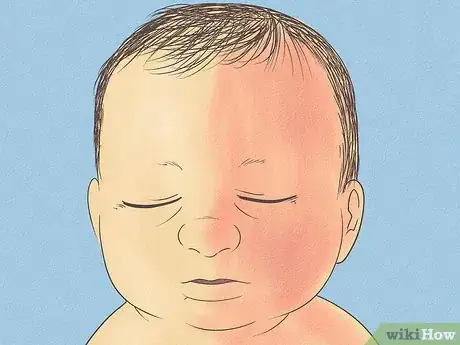

5Take note of harlequin coloring. This condition causes a newborn to be red on one side and pale on the other.[33] It may occur when the newborn lies on his or her side, and it happens because the newborn’s circulatory and related systems are still developing.[34] The coloring may develop suddenly, but usually goes away soon (within twenty minutes), after the infant is active or cries.

- Harlequin coloring is most common within the first three weeks of a newborn’s life.

Watching out for Potential Complications

-

1Care for diaper rash.[35] If a wet diaper is worn for a long time, or if urine and/or stool irritate the infant’s skin, diaper rash can result. An infant’s bottom or genitals may become red and sore, causing discomfort and irritability. However, the condition can be easily treated at home. Usually, diaper rash will be avoided or disappear within twenty-four hours if:[36]

- Diapers are changed frequently

- The infant’s skin is washed carefully

- A non-prescription diaper ointment is applied at diaper changes

-

2Let your doctor know if your newborn’s skin is yellowish. This condition, called jaundice, is common in infants and is not usually associated with a disease or problem. It may cause yellowing of the skin, or orange or greenish in some cases.[37] [38] It may show up 24 hours after birth and peak at about 72 hours. It appears because an infant builds up a substance called bilirubin, and can have a number of causes ranging from not getting enough breast milk to the newborn having an immature liver.[39] Usually, jaundice will clear on its own within a few days, but frequent feeding (every 2-3 hours) and a phototherapy treatment are also be recommended:

- Phototherapy treatments expose the infant to light, which helps to eliminate bilirubin. Your physician will explain what phototherapy to use, if one is deemed necessary.

-

3Look for any light brown spots. Light tan spots (sometimes called café-au-lait spots) may appear at birth or develop in a child’s first few years.[40] If many of these spots (or especially large ones) are present, your doctor will monitor your child, since they may be a sign of a condition called neurofibromatosis.

-

4Monitor any moles. There may be moles present on your newborn, called congenital nevi.[41] These can vary in size: they may be as small as a pea, or large enough to cover an entire limb. Your doctor will inspect and monitor nevi, since large ones have a greater risk of becoming skin cancer.

-

5Have your physician examine any large purplish blotches. Port wine stains (large purple-red patches) are often harmless, but could be a symptom of an underlying issue such as Sturge-Weber syndrome or Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber syndrome.[42]

-

6Have your physician examine any lumps that appear on your infant’s skin. Fat necrosis is a movable lump underneath the surface that appears on some infants. Though fat necrosis is often benign and will go away on its own within a few weeks, your doctor will want to examine the lump to make sure that it is not related to another condition (such as renal disease or hypercalcemia).[43]

-

7

-

8Contact your physician if you have any concerns.[46] If you feel that your baby is acting unusually, or if he or she develops unexplained skin conditions, talk to your physician, especially if you notice:

- Pain, swelling, or warmth in an area of your baby’s skin

- Red streaks extending from an area on his or her skin

- Pus

- Swollen lymph nodes

- Fever (38°C / 100.4°F or higher)

- Your baby is unusually fussy

References

- ↑ http://www.duq.edu/academics/schools/nursing/newborn-assessment/skin

- ↑ https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/002301.htm

- ↑ http://www.uofmchildrenshospital.org/healthlibrary/Article/88221

- ↑ http://www.chop.edu/conditions-diseases/skin-color-changes-newborns#.Vd0p0c7fgQV

- ↑ http://www.chop.edu/conditions-diseases/skin-color-changes-newborns#.Vd0p0c7fgQV

- ↑ http://newborns.stanford.edu/PhotoGallery/Pigment1.html

- ↑ http://www.duq.edu/academics/schools/nursing/newborn-assessment/skin

- ↑ http://newborns.stanford.edu/PhotoGallery/AngelKiss1.html

- ↑ http://www.duq.edu/academics/schools/nursing/newborn-assessment/skin

- ↑ http://www.womenandinfants.org/havingababy/yourbabyshealth/normal-newborn-appearance.cfm

- ↑ http://www.allinahealth.org/mdex/ND0343G.HTM

- ↑ https://myhealth.alberta.ca/health/pages/conditions.aspx?hwid=zx1747

- ↑ http://www.duq.edu/academics/schools/nursing/newborn-assessment/skin

- ↑ http://newborns.stanford.edu/PhotoGallery/Peeling1.html

- ↑ https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/002301.htm

- ↑ http://www.duq.edu/academics/schools/nursing/newborn-assessment/skin

- ↑ https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/002301.htm

- ↑ https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/002301.htm

- ↑ https://myhealth.alberta.ca/health/pages/conditions.aspx?hwid=zx1747

- ↑ http://www.aafp.org/afp/2008/0101/p47.html

- ↑ https://myhealth.alberta.ca/health/pages/conditions.aspx?hwid=tm6352spec&#tp21114

- ↑ http://www.duq.edu/academics/schools/nursing/newborn-assessment/skin

- ↑ http://newborns.stanford.edu/PhotoGallery/Lanugo1.html

- ↑ https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/002301.htm

- ↑ http://www.duq.edu/academics/schools/nursing/newborn-assessment/skin

- ↑ http://newborns.stanford.edu/PhotoGallery/Milia1.html

- ↑ http://www.duq.edu/academics/schools/nursing/newborn-assessment/skin

- ↑ http://newborns.stanford.edu/PhotoGallery/SlateGrey1.html

- ↑ https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/002301.htm

- ↑ http://newborns.stanford.edu/PhotoGallery/ETox1.html

- ↑ http://newborns.stanford.edu/PhotoGallery/Etox2.html

- ↑ https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/002301.htm

- ↑ http://www.duq.edu/academics/schools/nursing/newborn-assessment/skin

- ↑ http://www.aafp.org/afp/2008/0101/p47.html

- ↑ https://myhealth.alberta.ca/health/pages/conditions.aspx?hwid=zx1747

- ↑ https://myhealth.alberta.ca/health/pages/conditions.aspx?hwid=diras&#hw250399

- ↑ http://www.duq.edu/academics/schools/nursing/newborn-assessment/skin

- ↑ http://www.uofmchildrenshospital.org/healthlibrary/Article/88221

- ↑ http://www.med.umich.edu/1libr/pa/umphototherapy.htm

- ↑ https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/002301.htm

- ↑ https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/002301.htm

- ↑ http://newborns.stanford.edu/PhotoGallery/PortWine1.html

- ↑ http://newborns.stanford.edu/PhotoGallery/SubQ1.html

- ↑ http://www.uofmchildrenshospital.org/healthlibrary/Article/88221

- ↑ http://www.chop.edu/conditions-diseases/skin-color-changes-newborns#.Vd0p0c7fgQV

- ↑ https://myhealth.alberta.ca/health/pages/conditions.aspx?hwid=zx1747

- ↑ http://newborns.stanford.edu/PhotoGallery/Skin.html

- ↑ https://www.urmc.rochester.edu/encyclopedia/content.aspx?ContentTypeID=90&ContentID=P02628

Medical Disclaimer

The content of this article is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, examination, diagnosis, or treatment. You should always contact your doctor or other qualified healthcare professional before starting, changing, or stopping any kind of health treatment.

Read More...