This article was co-authored by Jamie Freyer, DVM. Dr. Jamie Freyer is a Licensed Doctor of Veterinary Medicine based in Washington. With over ten years of experience in clinical practice and industry, she specializes in veterinary medicine and surgery, animal behavior, and animal genetics. Dr. Freyer holds a BS in Life Science from The University of Portland and a DVM from Oregon State University.

There are 8 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page.

This article has been viewed 63,482 times.

Hip dysplasia is the abnormal development (dysplasia) of a dog’s hip joints. Genes are a major factor to developing this condition, so dogs can inherit hip issues from their parents or be susceptible to hip dysplasia because of their breed. As a general rule, larger pure breed dogs tend to carry the genes for hip dysplasia, so this condition is especially prevalent in German Shepherds, Labradors, Golden Retrievers, and Rottweilers.[1] If your dog is properly diagnosed with hip dysplasia and gets the proper medical attention, it's possible for him to live a happier life with less hip pain.

Steps

Part 1: Recognizing the Signs in Young Dogs

-

1Pay attention to the shape of your dog’s back. If your dog is experiencing low-grade hip pain, subtle signs like your dog’s posture and the shape of their back may be one way to detect hip dysplasia.[2]

- If your dog suffers from hip dysplasia, they may have a sloping back when they stand. Their back may be arched and their pelvis may be tucked underneath them, giving the impression of a back sloping down to the pelvis, rather than a flat, level back.

- Many pups who inherit hip dysplasia from their parents will show signs of the condition at less than 12 months old, so if your dog develops a sloping back at a young age, this may be a warning sign.

-

2Look at how your dog walks. If your dog is taking short, mincing steps with their back legs, rather than long, easy strides, this may indicate he is experiencing pain or discomfort in his hips. One of the consequences of hip dysplasia is premature arthritis, so younger dogs with this condition may experience issues usually associated with older dogs, such as inflammation, pain, and bone remodeling.[3]

- Your dog may also develop a habit of transferring weight onto his front legs to relieve any pain in his back legs and leaning forward, so the muscles of his forequarters will be more developed than the muscles of his rear end.

Advertisement -

3Check if your dog is hopping rather than walking. Some dogs with two sore hips will “bunny hop” instead of walk. Rather than move each leg independently and stepping with alternating legs, your dog may move his two back legs as one unit and “hop” forward.

-

4Notice if your dog doesn’t want to hop into the car or climb up the stairs. Dogs with hip issues may be reluctant or unable to perform activities that require propulsive power from their back legs like climbing stairs, jumping into a car, or leaping over objects.

-

5Take your dog to the vet if your dog displays lameness. Because the signs of hip dysplasia in young dogs are not very obvious, it can be difficult for you as the owner to realize something isn’t right until the dog goes completely lame. When your dog displays lameness, this may appear to be short term injury but in fact may be a more serious issue like hip dysplasia. To be certain, take your dog to the vet to get tested.

Part 2: Recognizing the Signs in Older Dogs

-

1Determine if your dog has a history of lameness or hip issues. Older dogs may have been lame at a young age and then recovered, only to have other hip problems develop later in life. If your dog has a history of hip issues, they may have hip dysplasia but missed being diagnosed or were misdiagnosed.

-

2Check if your dog appears stiff or in pain after lots of exercise. Older dogs with hip dysplasia may be stiff or have discomfort after lots of running around and playing.

- They may also have hind leg lameness that clears up after they rest, only for it to reoccur once they start using their muscles and exerting themselves.

-

3Take your dog to the vet if your dog displays lameness. While older dogs have many other possible health issues, properly diagnosing hip dysplasia in an older dog will ensure they live a less painful and much longer life.

Part 3: Getting a Professional Diagnosis

-

1Allow your vet to watch your dog walk and run. Your vet will stand directly behind your dog as he walks and runs. She is looking at the degree of his pelvic roll and if one hip joint bobs up and down more than the other. She will also look at your dog run and walk from the side to look a the length of his stride, whether the hind leg stride matches the front stride, and if both back legs strike out at the same distance or if one leg takes smaller steps.

-

2Allow your vet to analyze your dog’s muscle development. Your vet will be checking if your dog’s thigh muscles are well-developed or if they are weak and it is easy to feel the bones beneath the skin.

- If a young dog has weak muscle development, this means he is not exercising as much as he should because he is likely uncomfortable or in pain.

-

3Let your vet examine your dog’s back leg joints. Your vet will also look at each joint in your dog’s back legs to ensure the pain is localized to your dog’s hip joints. Just because a dog has hind leg lameness, this doesn’t mean the problem lies in his hips, as a sprained toe, a sore ankle, or a damaged ligament may be the source of the issue.

- Once your vet is assured the other joints are sound and there is no heat or swelling on other joints, she can focus her exam on your dog’s hips.

-

4Allow your vet to look at the range of motion of your dog’s hips. Your vet will extend your dog’s leg backward to test how sensitive his hip joint is. If your dog pulls against this movement, he clearly has a sore hip, as he will want to keep it as still as possible and not move it to avoid pain.

- A dog with supple, healthy hips will allow the leg to be moved with almost balletic flexibility, while a dog with a dysplastic hip will move stiffly. The range of motion of a normal hip is in all directions, so a dog with hip dysplasia will have limited to no range of motion.

- In severely dysplastic hips, there be the sound or impression of bone clunking against bone, as the vet manipulates the hip joints. This occurs because the joint space is uneven, allowing the bone to literally rub against another bone.

-

5Get an x-ray of your dog done while he is under a general anesthetic. As your dog’s hips will be too sore to tolerate the legs being held in position to get the correct view for an x-ray, a general anesthetic will be used to get an ideal position of his hips.[4]

- The vet will check for landmarks on the radiograph like the angle of the femoral neck, making sure the femoral head (ball joint) joins onto the shaft of the femur (thigh bone) on a short neck, at an angle of 45 degrees. A dog with dysplasia will have an almost straight femur heading into the femoral head. A healthy joint sits deep in the socket, so another indication of a poor hip is the ball barely sits in the socket.

- The vet will also check that there is even joint space between the ball and the socket and that the ball joint is rounded rather than square. Dysplastic hips often resemble a square peg in a round hole, with a block-shaped femoral head or ball sitting in a scoop shaped socket.

-

6Make sure your vet does an Ortolani test on your dog. Confirming hip dysplasia based on how your dog’s hips look on an x-ray is problematic, as an x-ray does not illustrate the degree of pain or lameness your dog might be experiencing. So make sure an Ortolani test is done by your vet in conjunction with an x-ray.[5]

- Under anesthesia, your dog will lie on his back with his thigh bone pointing towards the ceiling and his knee flexed. The vet will put pressure on the femur via your dog’s knee. If your dog’s hip is unstable, the hip bone will slip slightly out of joint, sometimes heard or felt as a “clunk”. The vet will then press the hip toward the pelvis, relocating the hip with another “clunk”.

- These “clunks” and the hip’s ability to dislocate out of the joint indicates the hip joint is not being supported properly by your dog’s ligaments and muscles, a clear sign of hip dysplasia.

Part 4: Understanding Hip Dysplasia

-

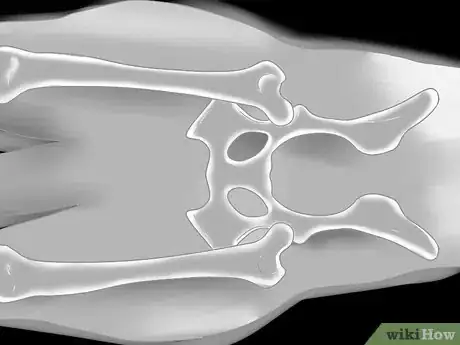

1Become familiar with the basic anatomy of the hip. A clear sense of hip anatomy will help to better grasp how hip dysplasia can occur in your dog.

- The hip is a ball and socket joint. The femur (thigh bone) ends in a ball (the femoral head) which sits in a boney cup (the acetabulum) in the pelvis. Much like a ball bearing running smoothly on a track, the perfect hip joint moves smoothly because the cup (acetabulum) is the perfect fit for the ball (femoral head).

-

2Be ware of the factors necessary to avoid pain in your dog’s hips. Even joint space, where the gap between the femoral head and the acetabulum is even all the way around and does not narrow or flare wider in certain areas, as well as the correct angle of the femoral head, all lead to healthy, pain free hips.

- Maintaining a perfect angle of 45 degrees where the femoral head joins onto the femur is important because when your dog stands, they will transfer weight up the shaft of the femur to the femoral head. If the angle is too straight, which usually occurs in hip dysplasia, your dog’s body weight will not spread evenly through the joint.

- Another important factor is a tight soft tissue support network. A combination of muscles, ligaments, and tendons hold your dog’s bones in their correct alignment and allow for pain free movement. If this soft tissue network is too slack, which occurs in hip dysplasia, it allows the bones to move around too freely and they can bump and grind against one another an unhealthy way, leading to serious pain for your pup.

-

3Think about restricting your dog’s diet to combat hip dysplasia. Studies have shown that a restricted diet for susceptible breeds can lead to a 46 percent decrease in cases of hip dysplasia. Feeding dogs to lessen their weight can also lessen the stress on their hip joints.

- However, a restricted diet does not alter the genetic predisposition to hip dysplasia found in larger dog breeds.

Expert Q&A

-

QuestionShould dogs with hip dysplasia climb stairs?

Jamie Freyer, DVMDr. Jamie Freyer is a Licensed Doctor of Veterinary Medicine based in Washington. With over ten years of experience in clinical practice and industry, she specializes in veterinary medicine and surgery, animal behavior, and animal genetics. Dr. Freyer holds a BS in Life Science from The University of Portland and a DVM from Oregon State University.

Jamie Freyer, DVMDr. Jamie Freyer is a Licensed Doctor of Veterinary Medicine based in Washington. With over ten years of experience in clinical practice and industry, she specializes in veterinary medicine and surgery, animal behavior, and animal genetics. Dr. Freyer holds a BS in Life Science from The University of Portland and a DVM from Oregon State University.

Licensed Veterinarian That's not a good idea. If possível, try to make it so that your dog doesn't have to use the stairs as often. If you have a smaller dog, you can carry it up and down the stairs. For larger dogs, depending on your house, you can make it so that the dog lives on mostly one floor so it doesn't have to go up and down the stairs.

That's not a good idea. If possível, try to make it so that your dog doesn't have to use the stairs as often. If you have a smaller dog, you can carry it up and down the stairs. For larger dogs, depending on your house, you can make it so that the dog lives on mostly one floor so it doesn't have to go up and down the stairs.

References

- ↑ Breed Dispositions to Disease in Dogs and Cats. Gough & Thomas. Publisher Wiley-Blackwell. 2nd edition

- ↑ Diagnosis of Hip Dysplasia. Saunders, Godefroid, & Snaps. Vet Rec. 145, (4), 109-112

- ↑ Diagnosis of Hip Dysplasia. Saunders, Godefroid, & Snaps. Vet Rec. 145, (4), 109-112

- ↑ Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment of canine hip dysplasia. Cook, Tomlinson, Constantinescu. Comp. Cont. Educ. Pract. Vet 19, p 853-867

- ↑ Coxofemoral joint laxity and the Ortolani sign. Chapman & Butler. JAAHA 21, pp 671-676

- Breed Dispositions to Disease in Dogs and Cats. Gough & Thomas. Publisher Wiley-Blackwell. 2nd edition

- Diagnosis of Hip Dysplasia. Saunders, Godefroid, & Snaps. Vet Rec. 145, (4), 109-112

- Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment of canine hip dysplasia. Cook, Tomlinson, Constantinescu. Comp. Cont. Educ. Pract. Vet 19, p 853-867

- Coxofemoral joint laxity and the Ortolani sign. Chapman & Butler. JAAHA 21, pp 671-676