This article was co-authored by Amy Chapman, MA. Amy Chapman MA, CCC-SLP is a vocal therapist and singing voice specialist. Amy is a licensed and board certified speech & language pathologist who has dedicated her career to helping professionals improve and optimize their voice. Amy has lectured on voice optimization, speech, vocal health, and voice rehabilitation at universities across California, including UCLA, USC, Chapman University, Cal Poly Pomona, CSUF, CSULA. Amy is trained in Lee Silverman Voice Therapy, Estill, LMRVT, and is a part of the American Speech and Hearing Association.

This article has been viewed 30,479 times.

Learn these basics for evaluating singing techniques and potential teachers, and be introduced to some good vocal exercises by an accredited voice teacher.

Steps

Pursuing Good Vocal Technique

-

1Learn to recognize the following characteristics of healthy vocal technique:

- It does not hurt your larynx (voice box).

- It makes notes on each end of your range more accessible.

- It helps you sing in tune.

- It empowers you to sing longer without fatigue.

- It is based on low breathing, and thinking a constant line of air.

- It uses word images to help you naturally access good placement without the tension which comes from trying to manipulate various parts of the anatomy directly.

- It tires the brain, but not the voice.

- It will train you to recognize your good singing apart from mere sound (since acoustics are variable and deceptive) by bodily sensation plus visual cues in the mirror.

- It will not push the chest voice (where most people speak) into an uncomfortable or range (where the physics work against you, producing tension), but uses the head voice for higher notes.

- It connects from the head voice downward to make a seamless and large vocal range that matches from top to bottom, possibly using the downward siren to teach this element.

- It produces volume (loudness) from breath equilibrium, facial vitality, and vowel shape, never from forcing.

- It helps young voices develop healthy singing habits but doesn't push them to sound like adults in volume or timbre.

- It provides clear, attainable, stepwise objectives, so you know what is expected and how to get there.

- It uses positive instruction and affirmation, not discouragement.

- Following it gives you a good chance of singing better at age 50 than you did at age 21.

-

2Get a good voice teacher. There are many limits to learning vocal technique from online advice:

- A good voice teacher teaches each student a bit differently based on their needs and the way they respond to his directives. Though you can learn some basics from "reading up" or videos online, the approach will not be tailored to your needs. If you really must use only online material, then you should read many sources, using only those that work for you.

- Many who give vocal advice online are not accredited teachers, and may be entirely untrained in healthy singing technique and teaching strategies. Professional vocal teachers will differ in how they approach the voice, and the style of singer they hope to produce. Find a teacher that is a good match for your desires and learning style.

- If possible, seek one in the music department at a good university. Many music theater singers are taught to push the chest voice fairly high. If you take from a music theater professor, check with them about how they teach regarding the chest voice. In either department, ask around to see who is producing the best students, and ask if you may audition for them. Another option is to seek out excellent singers with music degrees, such as school teachers, who take a few students. If possible, attend a recital or master class to get a glimpse of their results.

- If you are under age 18, enroll in choral music at your school, especially if the music teacher has a degree in vocal music. Start learning piano now, because the best voice teachers only take students who play well enough to learn their own songs without help. Piano instruction is more important than vocal instruction for anyone under age 18 who wants to be a singer.

Practicing Good Vocal Technique

There is no foolproof solution for vocal damage. Popular singers may rely on cortisone to restore them after a demanding concert schedule, but nodes which persist after vocal rest are only addressed by surgery, which can leave one with less vocal tone than ever. At the very least, nodules can take the sparkle out of your voice, removing your ability to sing all the notes in a scale or teach a weekend seminar. Remember that singing trends come and go, and the populace that falls at the feet of death metal screamers today may decide five years from now that crystal-clear young-sounding voices are only thing.

-

1Space out your singing engagements or long rehearsals to have at least one day between.

-

2Don't clear your throat (ahem) with that grating of vocal folds against each other. Instead, drink plenty of water to thin mucus, which is a natural lubricant for vocal folds. Use an expectorant when needed to cough efficiently and gently after a cold. You needn't clear all mucus off the vocal folds in order to sing. With good breathing technique, you can sing through the phlegm, and no one farther away than 3 feet (0.9 m) will hear it, though you hear it rattle inside your head.

-

3Don't whisper to preserve your voice. Whispering is actually worse than shouting.

-

4If you are vocally sore, get a pad and paper and put yourself on vocal rest.

-

5Stop smoking (or don't start).

-

6Avoid using the glottal stop in your speech and singing.

-

7If allergies plague you, consider allergy testing or adjusting your diet or environment to alleviate them. Many people respond to milk by an increase in mucus production. If you know you are singing in the afternoon, it may be worthwhile to use almond milk in the morning instead of real dairy.

-

8If you are a cheerleader, have your voice teacher train you to shout correctly. In general, avoid shouting. Cheer in a crowd by applause or whistling at games, etc.

-

9When laughing, don't let sound continue on the inhale.

-

10Don't imitate the Wicked Witch of the West. If you do voice-overs, use good sense in how you produce different characters.

-

11If you do theater, get the volume for your voice to carry in a healthy way. If you can't get that volume without yelling and straining, your voice is probably not really mature enough to do theater that is unaided by miking.[1]

-

12Don't speak in the gravelly basement part of your voice. Use voice inflection and nuance to keep a lilt in the voice, especially if you must use it often, as in teaching. If you are timid, raising the pitch of your speaking voice a little will help you sound more confident.[2]

-

13Use decongestants and anti-histamines wisely. If one of them makes you hoarse, find something better. For some people, taking 4 alfalfa tablets 3x per day is one acceptable alternative to other medications.

Exercises for Centering the Breath

-

1Jelly Belly: Put your hand on your belly at navel level to monitor movements. When breathing, you ideally should let the gut drop, relaxed like a big, fat, jelly belly. Though the belly is lower than the diaphragm, letting organs hang out for the breath makes more room for it to descend and gives you a feeling of relaxation and energy. Blow air out. Each time you breathe, let the dropping of the gut create the vacuum that sucks air in for you. You do not have to suck in air, just open up and let it come in. Check shoulders to see that they are hanging naturally back and relaxed, not jerking upwards during breathing.

-

2Puffing P's: With hand still monitoring belly movement, try some explosive p sounds, letting the p come from the belly area. As you "p-", the abdomen should naturally press itself inward with the puff of air.

-

3Panting Dog: Keeping in mind the low feel for your breathing source, open your mouth, let your tongue hang out, and keeping everything relaxed in jaw and throat, do puffs of air from your ab, training yourself to think low in the body and keep the throat uninvolved in the process of air intake.

-

4The Catch-Breath: At the end of a phrase, expel or express the final consonant well to create a springboard-type energy that enables your next breath to pop in naturally as you let the abdominal muscles relax. It enables a quick breath centered low in the body, setting you up well for the next phrase.

Exercises for Connecting the Voice to the Breath

-

1Siren: Breathing low in the body, start in a place high in your voice but not uncomfortable, and on "ah," siren downward. This is a siren, not singing. Don't try to make it pretty. Just make it very connected, the same vowel all the way through, all of the sound smoothly sliding, with no breaks in the sound. The sound rides on the breath, so the breath must be steady. You will use less volume of air for this exercise than the breathing exercises above, which are exaggerated for purpose of defining the breathing method. If there are spots where breaks want to come in your siren, start a little above the spot and make your siren move more slowly through that area. Do not rush anything in this exercise. Take time to prepare your breath, and when you run out of breath, take time to get another well-seated breath before continuing the slide down. Imagine a line of sound coming from your mouth moving to or through the wall to keep the vowel siren steady. Make sure you have plenty of room in your mouth for the "ah" as if pleasantly surprised, but NOT yawning. You may try this on different vowels. Remember it is not singing. Slide through all the notes, but don't sing it like a scale. Many singers find this the most effective exercise for connecting the voice to the breath and getting a seamless sound throughout their range.

-

25-Note Slide: Start this exercise just like the slide, but slide from 5 down to 1, (i.e.G down to C), sliding through the notes. Now sing the actual notes, but don't change anything in your body mechanism. Keep the face just as open, air just as flowing, etc. Move the 5 notes up or down the scale to warm up your voice. Take time to feel the center of your breathing (belly) before beginning each 5-note phrase. Don't rush.

-

3Hawaiian Guitar: In the song you are learning, sing through the notes in a phrase or part of a phrase on your favorite vowel, or after some experience, on the vowels of the lyrics, sliding from one note to another just like your siren exercise. Take breaths more often than you would in singing it straight through, each breath low in the body. You are teaching your body to connect all the notes to the body and breath with a feeling of constant fluidity. Gradually try it faster. Consistent practice of this method integrates correct breathing into your muscle memory for the song you are working on.

-

4Vowels Only: After sliding through the pitches, try to sing the actual notes on either one vowel or the vowels of the lyrics, but don't change the feel in your body and face from when you were sliding.

-

5Clustering Consonants (to the beginning of each word. Vowels are the clothesline, and consonants are the clothespins. They intersect the line, but they don't stop it or cut it in two. Your consonants and diphthong vowels should occur at the last moment and be springboards for the next traveling vowel. They are liquid and supportive of the vocal line. Think a stretch through them from low in the body.You can re-think phrases in the following manner, first made popular by Robert Shaw to have a great vocal line in your singing: Written text=Don't know when I've felt so blue... Sung text = doh ntnoh wheh nah eevfeh ltsoh bloo. In other words, you are placing the ending consonant of the previous word onto the next word in the phrase. It works for some people as a nice little trick to get you singing a steady vocal line.

Exercises for Shaping the Vowels

-

1Say it, sing it: Looking in the mirror, say a phrase you want to sing in your best expressive speaking voice. Then sing it, but don't change your mouth shape. This is best done in a medium low vocal range. It help you find a vowel that sounds alive. If you know you have a poor speaking voice and lazy vowels, it may help you to pretend you are someone else you know who has a good speaking voice. Singing right after saying it helps you find your natural vowel shape and avoid pitfalls of having the mouth too closed or unnaturally wrenched open for singing.

-

2Upward slide: Try this exercise only if you can successfully breathe from the body and do the downward slide. Let your mouth and throat be loose. Get a body breath and do a loose, very slidy siren on "ah" oozing slowly upward. Keep the breath moving, and let it move faster as you go higher in pitch. The impetus of the increased air should naturally make your face want to open up to make room for more air. Let the face do that. While most people will not open up enough for their high notes by intuition, most people's faces will open up for them on this exercise. It becomes a gauge by which you can find how open your vowel must be and how much air it must ride on to sing with ease in the high range.

-

3Sneeze: Imagine a tickling feeling inside behind your nose and eyes similar to what you feel right before you sneeze. Sing your vowels with that added tickle behind them. This is one way to get a clear, ringing sound in your vowels.

-

4Pointy Triangle: This works well, especially for many women. Think of a triangle with a very small point at the peak behind the bridge of your nose. Let this triangle be there as you sing.

-

5Vowel Columns: Each vowel has a top part and a bottom part, visualized like a column of air or an organ pipe. If you sing with the vowel well-formed behind the eyes but not seated on the low-body breathing mechanism, you are lacking the low part, and vice versa. You want to feel the whole length of every vowel, both the ringing part behind the eyes and the settled part within the body. In the upper ranges, you may feel more lift of air behind the vowel, but it should still be a column, though the column may seem to have a point on the top. Feel like you are letting each vowel bloom into its full shape.

Exercises for Singing with Musicality

-

1Milk the Words: Feel a stretchiness and languorous enjoyment of each word sound. Enjoy them, like good saltwater taffy.

-

2Phrase Rainbows: Each phrase has a shape, and many are like rainbows, with a stretch to a climax in the middle, falling to resolution at the end. Trace the shape of a rainbow in the air as you think these phrases, and it may help you sing them expressively. Other phrases look more like a waterslide or a straight line. Learn to think about the shape of your phrase and connect through it, expressing that shape in your impetus and dynamics.

-

3Meaning of the words: Create your own inner story of what is going on between the lines of the text. Then, let your body and face express this naturally by thinking that "story line" underneath your singing. In order to do this, you must often research the poetry for full understanding, and you must be well-prepared with your general song-learning to add this extra layer. Don't be too hasty in breaking the mood at the end of the song, but let it linger while you keep your eyes fixed on the same spot for a moment, as if the frame froze at the end of the movie. This will help the mood you have set to be quite powerful.

Exercises for Breathing Properly

-

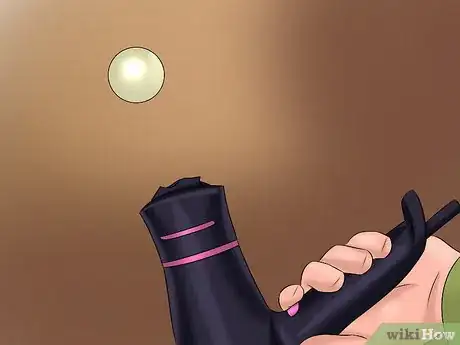

1Ping pong on the blow dryer: Picture your singing as a state of equilibrium in which your vocal sounds ride on top of your steady flow of air. If your air is a steady line with just the right amount of air volume, your singing will float along with the very best physics possible for the vibration of the vocal folds. Higher notes need a faster flow of air, but it is not a frantic, tension-filled increase, just a stretch into more connection.

-

2Rainbow breath gauge: In order to have enough air at the end of a phrase, think of tracing the phrase in the air as a rainbow, and this helps you know how much air you can spend at the beginning and still get to the end.

-

3Practice the end first: On long phrases you have determined need to be sung on one breath, practice the end without the beginning first. Getting the body used to singing the end well with plenty of breath and without closing down or tension trains its muscle memory to find a good approach to this spot. Practicing it this way often before connecting the parts sets you up for success. But also, consider whether it's the better part of valor (wisdom) find a spot to breathe somewhere in it. No one will notice where you breathe if you make the breath part of the expression of the piece, make it as much a part of the music as the sung notes. But everyone will notice if you creak or turn blue on the last note.

-

4Conveyor belt: Think of your line of breath as being like a conveyor belt that never stops during the singing.

-

5Line of air: Think a steady line of air. Your singing all rides on this constant line. Depending on the style or range of the notes, you may have a silvery thin line or a thick line like a decorative fountain spurting up many columns. Learn to picture that steady line of air in your practice, and it will come naturally during performance.

-

6Stretch through breaths: Sometimes we struggle to get back our equilibrium after stopping to breathe for the next phrase. Think a body stretch through the breath, and it will leave you ready for the phrase, not disengaged.

Exercises for Finding the High Range

-

1Kitty Squeaks (children and women) and Owl Hoots (changed-voice males): these sounds can be used to help you locate the place behind the eyes within your head from which the highest notes should seem to come. The kitty squeak helps women find their whistle voice range. Use a small puff of air to barely touch a whistle-like ah, ih, or ee. It is a short sound. You can pulse this sound on separated staccato notes til you find the place where it rings well and feels free. Immature or inexperienced singers may not be ready for this. Most males can easily find the Mickey Mouse-sounding falsetto by doing an owl hoot. Often oo or oh vowels help males locate the sweet spot for their high notes.

-

2Ping it, sing it: Use just enough air to touch or puff a staccato note for each note in a phrase. This (if it works for you) may help set you up for the note to ride on the column of air and for the right vowel shape for each note. After gauging with the staccato puff, sing through the whole phrase, using what you learned.

-

3Behind the front teeth: Some singers find it helpful to picture their highest notes as a line of sound exiting the mouth from behind the two upper front teeth, or at the alveolar ridge.

-

4Favorite vowel approach: Many people have a vowel that seems to work best for them on high notes. When learning a new high portion of a piece, try learning it on that vowel before switching to the real words.

-

5Making a space: many different word images can help you create the lovely space in which your high notes need to resonate. You may think of a snake face, with eyes bulging and jaw dropped, or a Disney heroine face, with wide, innocent eyes and a twinkle in them. Some like to think of the air flowing out of the top of their head, or an unraveling skein of yarn being pulled out from the top of their head.

-

6Scooping in: When learning new literature, as you are sliding through it, it can be useful to slide into a high note from below, to help you connect the breath. If it is an area where your chest (speaking) voice wants to go up uncomfortably high, however, then slide down to it instead.

-

7Sirening upwards as described above is great training for connected high notes.

Exercises for Finding the Low Range

-

1Falling forward: Healthy low notes will feel like they are falling forward out of your mouth, not being ground up out of your larynx. They are connected to the air, and flow out like liquid out of one of those fountains that has water coming out of the mouth of a fish. Low notes are not grabbed, but nurtured and allowed to happen.

-

2Slow slide, fast slide: Start near to your low range and slide very slowly down to it, keeping the line of air and keeping an open vowel. Then, start higher and make your slide quicker, seeing if you can still maintain the connection and openness.

-

3Space in mouth: Many people who open up well for high notes mistakenly think they must shut the mouth for low notes. This is not so. You must still provide space in the mouth and relax the jaw for low notes. The space behind the eyes may feel lower, however, as if behind the nose.

-

4Dog muzzle: It helps some people to think singing into a dog muzzle on their face when they ease into their low range.

-

5Feel it in the chest: Though you don't want to make it drop into the chest, rather fall forward from the face, you may feel more vibration or warmth in your chest area when using the low range.

Teaching Yourself

-

1If a certain vowel works well for you, try a difficult phrase singing it on that vowel to get you started approaching it.

-

2If a certain part in the song comes easily and another part is more difficult, sing the easy part first and sing the hard part immediately afterwards, while you are still in the easy vocal feel.

-

3Don't blaze through a whole song every time. Take out pieces of it to work on in isolation, training your body to sing each piece well. Then gradually put them back together.

-

4Use a mirror to check for body breathing, facial aliveness, good vowel shapes, enough room in the mouth,...etc.

-

5When learning music, play a short phrase on the piano, then sing it, matching pitch. If you have recording software, it may occasionally be useful to record this process to see how close you are coming and identify pitch areas you need to slide through in order to center the vowel and breathing for truly stunning pitch accuracy.

Singing in a Vocal Ensemble

-

1Come well-prepared so you don't let others down and strain your voice.

-

2Listen to others around you and blend, don't blast. Watch the conductor for tempo, dynamics, etc.

-

3Your own personal dynamics: Big voices in an ensemble may not be able to sing as softly as small voices. When asked for a pianissimo, find your own pianissimo. If you can't become soft enough for the group without vocal tension, lay own on that part and come back in subtly when the volume increases. Same with small voices, don't push harder than is healthy when asked for fortissimo. Sing "your" fortissimo.

-

4Vibrato: Some ensemble singing styles require the use of very subtle or even no vibrato. If you have natural vibrato and want to sing in a straight-tone group, seek the help of a capable teacher to learn how to sing with a simpler tone. You may, however, want to seek out a group that uses a style you produce more easily.

Ear Training

-

1Intervals by sound and sight - If you don't read notes and hear intervals (the distance between two given notes) in your head, you should seek help for ear-training if you want to be a capable singer.

-

2Rhythm - reading notes well enough to sing the rhythm accurately is also important.

-

3Chords and understanding harmony - to sing like a professional, you need to sense which part of the chord you are singing. This takes an understanding of harmony which is best learned, as are both of the above, by getting a good background in piano.

-

4Independence, dissonance - Learn to hold your pitch even when things compete or distract, such as a next-door-neighbor who sings flat in your ear. Try singing a familiar song with musical friends each a half-step apart from the others key-wise. If you practice such things, you'll be ready for contemporary choir pieces that have dissonance as their main expressive element, and you'll probably ace auditions where you have to sight-read in an ensemble group.

-

5Counterpoint - Some choral styles are an interweaving of stacked melodies. Your director should let you know which voice should be at the forefront, and which ones are to lie back and let it predominate. You will win the esteem of your director if you mark in your part what they've said and be careful to do it.

Warnings

- If ANY exercises on this page cause pain in your vocal folds (voice box), don't use them. (Stretchiness in the back of the throat is fine, but tension or pain in the vocal chords is not.) Not every exercise is for every person. Become your voice's best advocate by paying attention to your body's signals as you explore singing instruction resources.⧼thumbs_response⧽