This article was co-authored by wikiHow Staff. Our trained team of editors and researchers validate articles for accuracy and comprehensiveness. wikiHow's Content Management Team carefully monitors the work from our editorial staff to ensure that each article is backed by trusted research and meets our high quality standards.

There are 8 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page.

This article has been viewed 58,343 times.

Learn more...

If you’ve read a book that you think could be really great performed live, you don’t have to wait for someone else to write it—you can do it yourself! As long as the book is in the public domain or you have bought the rights to the book, you can adapt it to a play. You just need to know the book really well, plan your approach, and write the story so it can be performed.

Steps

Researching the Material

-

1Read the book multiple times, taking notes as you read. To be able to capture the story and do it well, you need to really know the book. Read it more than once and take notes on characters, plot lines, dialogue, and setting as you read.[1]

- If the book is based on a true story, take careful notes. You probably want to make sure you get the details as accurate as possible in your recreation.[2]

-

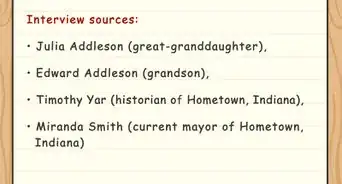

2Reach out to the original author to inquire about plot and characters. Developing a relationship with the original author can help you to make a much better play. If you are unclear on any reasons for character or plot development, asking the author would help you stay true to their story.[3]

- It’s not necessary to stick to the book with 100% accuracy. Playwrights often take creative liberties with changing up characters and narrative either because they have a different vision or they just need to shorten the story to make it stage-ready.

- If the original author is unavailable, another option is to see if you can track down the author’s family or friends to interview them about their thoughts on the work.

Advertisement -

3Know your contract and your rights to artistic freedom. If the book is not in the public domain then you need to have a contract explaining your rights to adapt the book. Seek legal assistance in drawing up a contract and don't hesitate to ask questions about anything you don't understand. Make sure you know exactly what kind of creative liberties you can take, what to do if the author is unavailable for consultation, and any other rules the original author has put forth.[4]

- Some examples of rules that might be in your contract are guidelines for changing the characters' names, setting, major themes, title of the work, etc.

-

4Do any necessary research for expanding and adapting the story. Think of the book as just one potential source for writing your play. When the author wrote the book, they likely did a lot of research and only some of it made it into the final product. In order to adapt the story, you have to fully understand the context, so do your homework on the narrative, settings, and historical background.

- If the book took place during a particular significant historical event—a war, for example— read up on the event, its causes, and how it affected people.

- Be sure to study the geography and culture of the people if the book is set in a place unfamiliar to you.

-

5Look up reviews for the book so you know what readers loved and hated. Read as many reviews of the book as you can to understand what people liked and did not like. Make note of characters that are favorites, criticisms waged, and favorite plot points. This way, you'll know how you can shorten the story and what you absolutely must keep. [5]

- You can find amateur and professional literary reviews online or in newspapers. Just search the title of the book and “reviews.”

Outlining Your Play

-

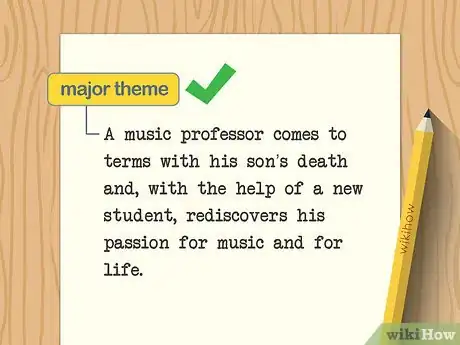

1Establish the major theme or storyline from the book. The theme is the major unifying element of the work. After you have done several reads and conducted research, you should be able to identify the story’s major theme(s). You do not have to stick exactly with the book's theme, however—you can develop it and change it to fit your vision.[6]

- The book may have more than one theme. To simplify your play, try to pick one and use it to structure your writing.

- Some examples of themes are love, struggle, good vs. evil, and death. Your entire story does not need to be only about the the theme, but everything you write should reinforce or illuminate elements of the theme eventually.[7]

-

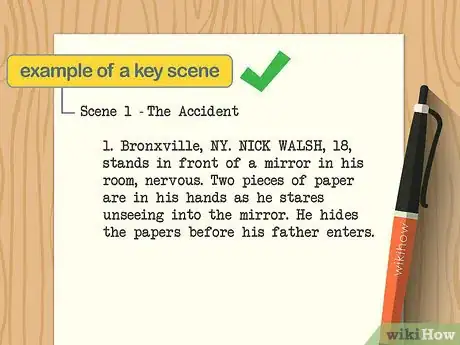

2Determine the key scenes from the book that connect to the theme. Choose 5-10 scenes from the book that directly relate to the major theme. These scenes will be what you base the rest of your narrative around.[8]

- You definitely need introductory scenes that explain the characters and the story. Then, you need scenes in which the story climaxes, and final scenes that wrap it up.

- Novels usually have entire chapters or sections that are dedicated to developing complicated backstories for characters. You won't have time to include them in your play.

-

3Combine characters and scenes to simplify and shorten the story. You will not be able to fit the entire book, all of its characters, and all of its scenes into a play. Therefore, you are going to have cut out a great deal of the book. One way to do this is to combine characters or scenes from the book that send the same message or have similar personality or plot points.

- For example, if you have two antagonists, consider combining those characters into one individual that embodies the traits of both in the book.[9]

- To figure out what to cut, decide on 5 things the audience must know. Then work to cut any extra detail that doesn’t directly apply to those 5 things.

-

4Write out the main ideas that inform the core conflict and how it unfolds. You want to have a solid sketch of the central problems your characters will face and what will happen to them along the way. If you have all of the details of the plot outlined you begin to write the dialogue, the story will flow smoothly.[10]

-

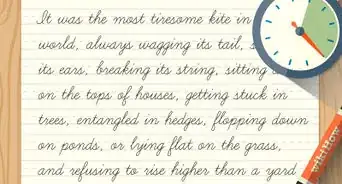

5Choose 10-20 favorite quotations from the book that you want in the play. Directly connect your play to the book with exact lines spoken by characters or written into the narrative. Choose the ones that really help really explain character and plot development.[11]

- People that are familiar with the book will enjoy recognizing these lines and more easily connect with your play.

- If the play is to be funny, pick the lines that made you laugh. If it's a drama, choose the lines that moved you. If you can connect with emotionally, you have a better chance of getting your audience to connect in the same way.

-

6Decide how many acts and scenes the play will have. Determining guidelines before you begin writing can help you to pace yourself and keep you motivated to keep going. Set goals for how many acts and scenes the play will have based on your outline and how much information you need to convey.[12]

- Many playwrights have relied upon a three-act basic structure. You can do that or you can go your own way based on whatever makes sense to you.

-

7Sketch out how you want the set to look. The set-up of the stage is really important for any play. The background, furniture, and props used should be thought of like additional characters in the story because they can help you communicate unspoken messages. Much of the set is determined by the set designer, but your sketches will help the designer understand what you were going for.[13]

- Think about the story and the characters as you sketch the set. Are the characters wealthy or poor? How might a set look for a story set in an aristocratic family’s home? A poor family’s? You can communicate a lot of information about the characters’ backstories through the set itself.

- Keep it simple. In the book there may be a hundred different locations. In a live performance, having more than a few settings would be confusing for the audience and make performing and designing the play unwieldy. Choose only the most important places and cut the others.

Writing for a Live Audience

-

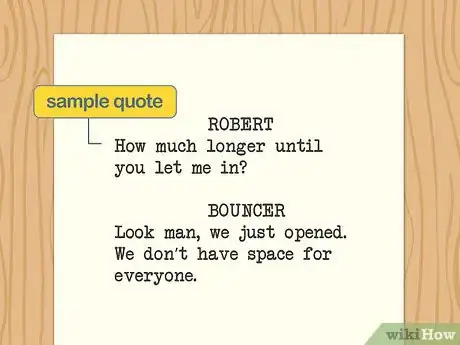

1Write out the dialogue the characters need to speak to convey the story. Begin writing by scripting out the dialogue that will be spoken. While other factors–like set and actions—will help communicate the story to the audience, the dialogue provides most of the narrative. Take your time and carefully write out the entire story from the mouths of your characters.[14]

- Review other play scripts to get a sense of how dialogue is written and the formatting of the text on the page. You don’t need to read entire plays, just scan several so you know what is expected of you.

-

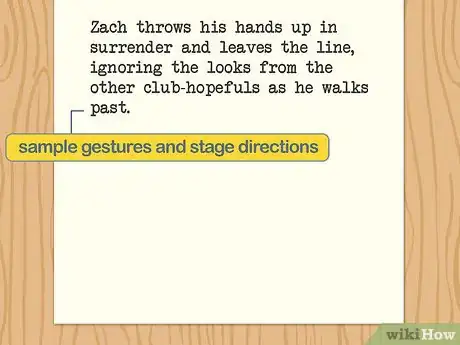

2Add grand gestures and stage directions to help the audience along. After you’ve constructed the dialogue, you want to write in stage directions for the actors. The actors movements need to be big and flamboyant so that even the people in the very back row can tell what they are doing and why.[15]

- The gestures should be written into the dialogue script at the points where they are to be performed.

- You do not need to script out every movement the actors will make, but you should write in several such as, “angrily slams doors” or “falls to the ground. weeping loudly,” that help your story come to life.

-

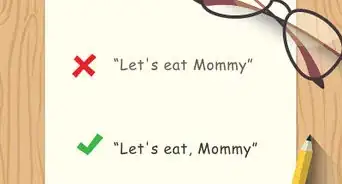

3Proofread your script by reading it several times and correcting any errors. Everyone makes mistakes as they write. Therefore, it’s really important that you proofread your writing multiple times after you think it’s done. It’s a good idea to step away from it for a few hours or a few days and then come back and revise it. This helps you disconnect from the story and see the writing better in terms of grammar and mechanics.[16]

- Pay special attention to wordiness in your writing. Since you are trying to communicate an entire book into a play that will only last a few hours, it’s really important to keep the writing as concise as possible. Look for times in your script where you get repetitive or give information that is not really necessary to the story itself.

Submitting Your Work

-

1Have an agent submit your script for you. Many theaters require recognized literary agents to submit work. The most common and direct way to see your play become a reality is to get an agent, if you don’t have one already, and let them do the leg work for you.[17]

-

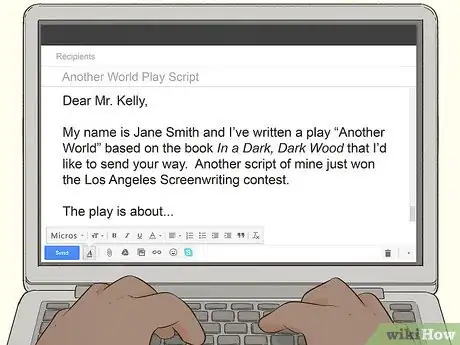

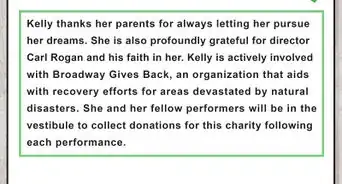

2Submit a query letter or proposal to theaters explaining your play. Send several local theaters or performing arts groups a one-page letter that gives information about the play, your experience, and why they should be interested. If they like your proposal, they’ll contact you and ask you for the script.[18]

- Contact the theaters in advance and ask them how they'd prefer to receive submissions. Some will only work with agents, some will want query letters, and some want the entire script up front.

-

3Send the script in its entirety to theaters that accept unsolicited work. You can send entire copies of the script to some theaters in order to gain some exposure for yourself and your writing. Include a cover letter and self-addressed stamped envelope so that the theater can reply.[19]

- If the theater tells you that it’s okay to submit either a proposal or the full script, it’s best to send just the proposal so that you can save money on printing and postage.

Community Q&A

-

QuestionWhat if the author is dead?

WestDoggiesCommunity AnswerAsk the publishing house that published the book. They will be able to tell you how you can get permission.

WestDoggiesCommunity AnswerAsk the publishing house that published the book. They will be able to tell you how you can get permission. -

QuestionThis is fantastic, but I'm having trouble choosing a book. How can I choose?

Community AnswerChoose your favorite book, or a book that you think would work well in play form. If you really can't decide, you can ask someone for an opinion or just choose randomly.

Community AnswerChoose your favorite book, or a book that you think would work well in play form. If you really can't decide, you can ask someone for an opinion or just choose randomly. -

QuestionIf I have gotten verbal permission from the author of the book, do I still need a formal contract?

Community AnswerYes, a formal contract should still be drawn up.

Community AnswerYes, a formal contract should still be drawn up.

References

- ↑ https://www.scriptmag.com/features/craft-features/adapting-a-book-into-a-screenplay

- ↑ https://www.scriptmag.com/features/craft-features/adapting-a-book-into-a-screenplay

- ↑ https://filmmakermagazine.com/76583-adapt-or-die-13-steps-to-adapting-a-film-from-something-else/#.XPledNNKgWp

- ↑ https://www.aclu.org/other/freedom-expression-arts-and-entertainment

- ↑ https://filmmakermagazine.com/76583-adapt-or-die-13-steps-to-adapting-a-film-from-something-else/#.XPledNNKgWp

- ↑ http://blog.janicehardy.com/2013/02/theme-me-up-how-to-develop-your-theme.html

- ↑ https://writersedit.com/fiction-writing/10-most-popular-literary-theme-examples/

- ↑ https://www.scriptmag.com/features/craft-features/adapting-a-book-into-a-screenplay

- ↑ https://www.scriptmag.com/features/craft-features/adapting-a-book-into-a-screenplay

- ↑ https://www.scriptmag.com/features/craft-features/adapting-a-book-into-a-screenplay

- ↑ https://www.scriptmag.com/features/craft-features/adapting-a-book-into-a-screenplay

- ↑ https://www.writerscookbook.com/stage-play-writing-ingredients/

- ↑ https://www.writerscookbook.com/stage-play-writing-ingredients/

- ↑ https://www.writerscookbook.com/stage-play-writing-ingredients/

- ↑ https://www.writerscookbook.com/stage-play-writing-ingredients/

- ↑ https://writing.wisc.edu/handbook/grammarpunct/proofreading/

- ↑ http://www.playwriting101.com/chapter16

- ↑ http://www.playwriting101.com/chapter16

- ↑ http://www.playwriting101.com/chapter16