This article was medically reviewed by Shari Forschen, NP, MA. Shari Forschen is a Registered Nurse at Sanford Health in North Dakota. Shari has worked in healthcare since 1996 and her expertise lies in acute care bedside nursing on a medical oncology floor. She received her degree from Medcenter one College of Nursing in 2003 and her Family Nurse Practitioner Masters from the University of North Dakota in 2014. Shari is a member of the American Nurses Association.

There are 10 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page.

wikiHow marks an article as reader-approved once it receives enough positive feedback. In this case, 88% of readers who voted found the article helpful, earning it our reader-approved status.

This article has been viewed 70,450 times.

Tics are involuntary repetitive movements and sounds that are difficult or impossible to control. They involve sudden jerky movements of the head, face, neck and/or limbs, as well as repetitive vocalizations. Tics are relatively common during childhood and are often diagnosed as either Tourette Syndrome (TS) or Transient Tic Disorder (TTD) based on severity and duration of symptoms. If the tics are more severe or pervasive and last beyond a year, then TS is likely. In contrast, TTD involves milder symptoms that are short-lived or transient. Dealing with both conditions appropriately is important for children to be able to get over their tics or better control them

Steps

Distinguishing Between Tourette's and Transient Tic Disorder

-

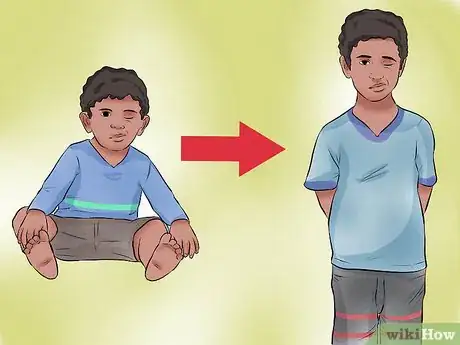

1Take note of the person's age. Tics due to TS typically show up between the ages of 2-15, with the average age being near 6 years of age.[1] TS often lasts into adulthood, but it always starts during childhood. TTD is also a childhood disorder, and in fact, the transient tics need to occur before the age of 18 years to be diagnosed as such.[2] There's a lot of overlap between the two conditions in terms of age of onset, but TS often begins at a little younger age because of genetic links.

- Tics that develop in adulthood for the first time are typically not diagnosed as either TS or TTD. Both conditions must originate during childhood to be diagnosed as such.

- Boys are approximately three to four times more likely than girls to develop TS and TTD.

-

2Watch for vocalizations. For a child to be diagnosed with TS by a doctor, they must exhibit both motor tics and vocal tics. Motor (movement) tics can include excessive blinking, nose twitching, grimacing or shoulder shrugging. Vocalizations can include simple grunts and repetitive throat clearing, or more complex verbalization such as yelling out words or phrases. Multiple types of motor and vocal tics in the same child is not uncommon with TS. In contrast, most kids diagnosed with TTD have either a single motor or vocal tic, but rarely both during the same time frame.

- When repetitive words and phrases are spoken, it's considered a more complex vocal tic. Kids with TS are more likely to display coprolalia (yelling out socially inappropriate words or phrases — vulgar swearing) and echolalia (mimicking the words or phrases of others).

- Despite how it's portrayed in movies and TV, coprolalia only occurs in 10 to 15% of people with TS.[3]

Advertisement -

3Observe how complex the tics are. Although TS varies from mild to severe in terms of repetitive behaviors and vocalizations, it tends to involve the more complex tics. Complex tics involve several different parts of the body and the movements typically have a pattern or rhythm — such as bobbing the head while jerking the left arm and yelling "Shut up".[4] By comparison, kids with TTD can also have complex tics, but not nearly as commonly as is seen in TS. Furthermore, TTD rarely involves complex motor and vocal tics at the same time.

- The most common first symptoms of both TS and TTD are facial tics (blinking, raising eyebrows, nose twitching, grimacing, sticking out tongues). Initial facial tics are often added to or replaced by tics of the neck, trunk and/or limbs.

- Tics of both TS and TTD often occur many times daily (usually in bouts or bursts of activity) nearly every day, although sometimes there are breaks.

- The tics often look like really nervous behavior and can get worse with stress. Interestingly, tics usually don't occur during sleep.[5]

-

4Notice how long the behavioral changes last. The duration of the abnormal behavior and tics is the biggest factor in distinguishing TTD from TS.[6] To be diagnosed with TTD, a child has to display a tic(s) for at least four weeks almost every day, but less than a year.[7] In contrast, for TS to be diagnosed, tics must be present for more than a year.[8] That's why time and patience are needed to get an accurate diagnosis and to distinguish between TTD and TS.

- Most cases of TTD fade away within weeks to months, well within the one year time period.

- Tics that last a year or a little more may be called "chronic tics" until enough time passes that qualifies for a TS diagnosis.

- TTD is much more common than TS. About 10% of kids develop TTD during their early school years, which later fades away.[9] In contrast, about 1% of Americans have mild TS and approximately 200,000 have severe TS (both kids and adults combined).

-

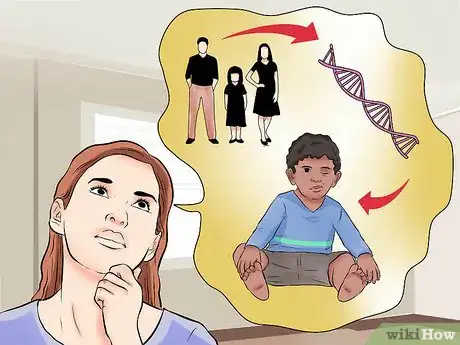

5Look for a genetic link. A relatively good predictor of potential tics in a child is seeing tic behavior in their parents, siblings or close relatives. TS, in particular, seems to have a relatively strong genetic link, whereas environmental factors (stress, abuse, diet) likely plays a larger role with TTD. Regardless, TS is regarded as a complex neurological disorder influenced by a combination of factors, including genetic (inherited), environmental, behavioral and chemical — especially the neurotransmitters in the brain called dopamine and serotonin.[10]

- An inherited genetic condition means that it's passed on from at least one parent to child through genes located on chromosomes.

- Research indicates that TS may involve inherited brain abnormalities in certain regions and circuits, as well as hormones called neurotransmitters — essentially communication among brain cells is disrupted or over-stimulated.

-

6Be aware of associated conditions. Another decent predictor of potential tic behavior (for both TTD and TS) is whether or not the child has previous "neuro-behavioral" problems such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) and/or autism. Significant problems with reading, writing and/or arithmetic may also be risk factors for developing tics.

- Obsessive compulsive behavior includes intrusive thoughts and worries combined with repetitive behaviors — worries about dirt / germs get associated with repetitive hand-washing, for example.

- TS in particular is strongly associated with co-occurring conditions. About 86% of children with TS also have at least one additional mental, behavioral or developmental condition — often either ADHD or OCD.[11]

Dealing with Tics

-

1Be patient and supportive. When you see a tic develop in your child, don't assume the worst — that it will become a severe case of TS lasting the rest of their life. Instead, be patient and supportive, while trying to create a less stressful environment for your child, either at home or at school. In the vast majority of cases, childhood tics vanish almost as quickly as they come on, within a few months. If your child has a tic for more than a year, then a diagnosis of TS is likely, but there's still a chance of it going away or becoming very mild and controllable.

- There are no blood, laboratory or brain imaging tests used for diagnosing tics. Most kids or adults are self-diagnosed after they, their parents / relatives or friends read or hear about TS or TTD.

- Chronic emotional, psychological and physical stress is associated with virtually every behavioral abnormality. Look at your child's daily routine and try to spot the major stressors, then alleviate them if you can.

-

2Don't bring too much attention to tics. Doctors, psychologists and counselors recommend that family members don't call much attention to the tics, at least at first.[12] This is because unwanted attention, especially if it's negative and involves anger or disparaging remarks, causes more stress that can make the tics worse. If the tics become complex and severe enough to cause social problems at school and/or work, then consider behavioral therapy and/or medications if they persist beyond a few months.

- If the tic doesn't go away within a week or, ask your child what's bothering them. Maybe they have allergies, a chronic infection or another illness. Short-term repetitive behavior is not always a tic.

- Don't mimic your child's tic in efforts to be humorous or playful — it may make them more self-conscious or nervous.

- Seeking therapy or medication for a mild tic in a child due to your embarrassment is not a good idea. Deciding on treatment should depend on if the tic behavior disrupts your child's life or has a real negative impact.

-

3Consider therapy. Cognitive behavioral therapy is usually the first line of treatment for tics that are not accompanied by ADHD or OCD. If the tics are severe enough to negatively impact a child's life, then some form of therapy should be considered, regardless if the diagnose is TTD or TS. Therapy is usually conducted by a child psychologist or psychiatrist and can involve cognitive behavioral interventions and/or psychotherapy.[13] During these sessions (multiple are often needed to be helpful) the child or adult should be accompanied by a close family member for support.

- Cognitive behavioral therapies typically include habit-reversal training, which helps to identify the urge to tic and then learn to voluntarily combat it from happening.

- Most tics can't be stopped completely, but they can be made less obvious or forceful.

- Psychotherapy involves talking and asking probing questions. It can help more with accompanying behavioral problems, such as ADHD, OCD, depression and anxiety.

-

4Talk to your doctor about medications. There are medications to help control tics and reduce the effects of related behavioral problems, but they are not often recommended for TTD because of its temporary or transient nature.[14] Instead, these drugs are usually reserved for those kids or adults who suffer from severe TS. These psychotropic drugs can certainly change symptoms and behaviors, but they often have serious side effects, so weighing the pros and cons with your doctor is important.

- Drugs that help control tics by blocking or reducing dopamine in the brain include: fluphenazine, haloperidol (Haldol) and pimozide (Orap). Ironically, a possible side effect is more involuntary, repetitive movements.

- Botulinum (Botox) injections paralyze muscle tissue and may be helpful for controlling simple isolated tics of the face and neck.

- ADHD medications, such as methylphenidate (Concerta, Ritalin) and dextroamphetamine (Adderall, Dexedrine), can sometimes help with tics, but they can also exacerbate them too.

- Central adrenergic inhibitors, such as clonidine (Catapres) and guanfacine (Tenex), can help with impulse control and reduce rage.

- Anti-seizure drugs typically used for epilepsy, such as topiramate (Topamax), have proven helpful for some TS patients.[15]

Expert Q&A

-

QuestionCan my son withdraw from his medication for TS? He is on concerta and catapres.

Shari Forschen, NP, MAShari Forschen is a Registered Nurse at Sanford Health in North Dakota. Shari has worked in healthcare since 1996 and her expertise lies in acute care bedside nursing on a medical oncology floor. She received her degree from Medcenter one College of Nursing in 2003 and her Family Nurse Practitioner Masters from the University of North Dakota in 2014. Shari is a member of the American Nurses Association.

Shari Forschen, NP, MAShari Forschen is a Registered Nurse at Sanford Health in North Dakota. Shari has worked in healthcare since 1996 and her expertise lies in acute care bedside nursing on a medical oncology floor. She received her degree from Medcenter one College of Nursing in 2003 and her Family Nurse Practitioner Masters from the University of North Dakota in 2014. Shari is a member of the American Nurses Association.

Master's Degree, Nursing, University of North Dakota In general, medication should not be stopped abruptly unless discussed with treating physician. The catapres can cause withdrawal symptoms if abruptly stopped. Best advice is to discuss with your son's physician if he wants to discontinue medication.

In general, medication should not be stopped abruptly unless discussed with treating physician. The catapres can cause withdrawal symptoms if abruptly stopped. Best advice is to discuss with your son's physician if he wants to discontinue medication.

References

- ↑ https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/tourette/facts.html

- ↑ http://www.healthline.com/health/transient-tic-disorder#Diagnosis4

- ↑ https://tourette.org/resource/understanding-coprolalia/

- ↑ http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/tourette/facts.html

- ↑ https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/000747.htm

- ↑ http://www.aacap.org/AACAP/Families_and_Youth/Facts_for_Families/FFF-Guide/Tic-Disorders-035.aspx

- ↑ https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/000747.htm

- ↑ http://www.movementdisorders.org/MDS/About/Movement-Disorder-Overviews/Tics--Tourette-Syndrome.htm

- ↑ http://www.aacap.org/AACAP/Families_and_Youth/Facts_for_Families/FFF-Guide/Tic-Disorders-035.aspx

- ↑ http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/tourette-syndrome/symptoms-causes/dxc-20163624

- ↑ http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/tourette/facts.html

- ↑ https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/000747.htm

- ↑ http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/tourette-syndrome/diagnosis-treatment/treatment/txc-20163628

- ↑ http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/tourette-syndrome/diagnosis-treatment/treatment/txc-20163628

- ↑ http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/tourette-syndrome/diagnosis-treatment/treatment/txc-20163628

- ↑ https://tourette.org/about-tourette/overview/

Medical Disclaimer

The content of this article is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, examination, diagnosis, or treatment. You should always contact your doctor or other qualified healthcare professional before starting, changing, or stopping any kind of health treatment.

Read More...