This article was co-authored by Nitzan Levy. Captain Nitzan Levy is a Sailor, Social Entrepreneur, and the Founder of Sailors NYC, a recreational sailors’ club based in Jersey City, New Jersey that specializes in cruising boats and a variety of community programs. Capt. Levy has over 20 years of sailing experience and has sailed in many places around the world including: the Atlantic Ocean, the Mediterranean Sea, The Caribbean, and the Indian Ocean. Capt. Levy is a U.S. Coast Guard Licensed Master of vessels up to 50 Tons with Auxiliary Sail and Assistance Towing Endorsements. Capt. Levy is also a NauticEd Level V Captain Rank Chief Instructor, an American National Standards Assessor, an SLC instructor, an ASA (American Sailing Association) Certified Instructor Bareboat Chartering, and an Israeli licensed skipper on Boats for International Voyages.

There are 9 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page.

wikiHow marks an article as reader-approved once it receives enough positive feedback. This article received 25 testimonials and 93% of readers who voted found it helpful, earning it our reader-approved status.

This article has been viewed 916,433 times.

For centuries, the sea has captured the spirits of sailors and adventurers all over the world. In his poem "Sea Fever", John Masefield claimed that all he needed was "a tall ship and a star to steer her by" to feel complete. Breaking into the sailing world can be challenging, but this article will help guide you through the ebb and flood of the nautical world. As a note, this article will help get you started, but it cannot be overstated that before you begin, have an experienced sailor show you the standing and running rigging on your boat and their functions before you venture out on the water on your own.

Steps

Gaining a Basic Knowledge of Sailing

-

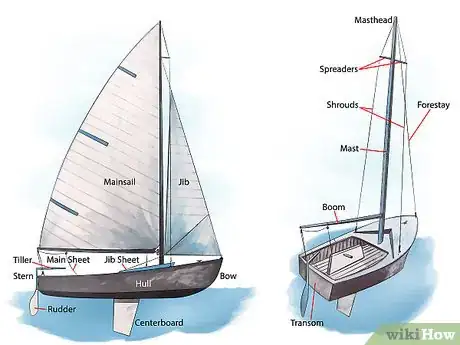

1Know the different parts of a sailboat. It is important to know the different parts both for safety reasons and to be able to sail your boat as efficiently as possible.[1] If you don’t know what to do when someone suddenly yells, “prepare to tack” or “watch the boom!” you may be in trouble.

- Block: This is the nautical term for a pulley.

- Boom: The horizontal support for the foot of the mainsail which extends aft of the mast. This is what you want to watch out for when changing directions in a sailboat. It can give you quite a wallop on the head if it hits you.

- Bow: This is what the front of the boat is called.

- Centerboard: This is a (usually fiberglass) plate that pivots from the bottom of the keel in some boats and is used to balance the boat when under sail.

- Cleat: Cleats are what lines (or ropes) get fastened to when they need to be kept tight.

- Halyard: Lines that raise or lower the sails. (Along with the sheets, aka running rigging.)

- Hull: The hull is the body of the boat and consists of everything below the deck.

- Jib: This is the sail at the bow of the boat. The jib helps propel the boat forward.

- Genoa: A foresail which is larger than a jib.

- Keel: The keel is what prevents a boat from sliding sideways ("making leeway") in whatever way the wind is blowing and stabilizes the boat.

- Line: Lines are ropes. They are everywhere on boats. There is only one "rope" on a sailboat, the bolt rope which runs along the foot of the mainsail.

- Mainsail: As the name implies, this is the mainsail of the boat. It is the sail attached to the back of the mast.

- Mast: The mast is a large, vertical pole that holds the sails up. Some boats have more than one mast.

- Painter: This is a line positioned at the front of small boats. It is used to tie the boat to a dock or another boat.

- Rudder: The rudder is how the boat is steered. It is movable so that when you turn the wheel or tiller, the rudder directs the boat in the direction you would like the boat to go.

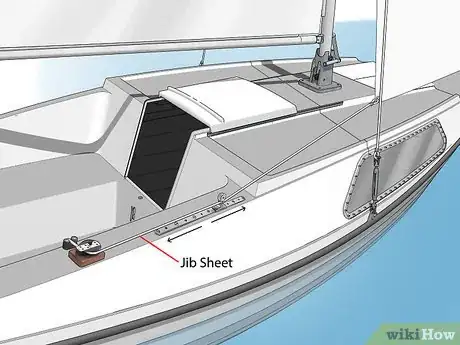

- Sheets: The lines that control the sails. (aka running rigging.)

- Spinnaker: The usually brightly colored sail used when sailing downwind or across the wind.

- Stays and Shrouds: Some wires make sure the mast stays upright, even in very heavy winds. (aka standing rigging.)

- Stern: This is the term for the back of the boat.

- Tiller: The tiller is a stick attached to the rudder and is used to control the rudder.

- Transom: This is what we would call the butt of the boat. It is the back part of the boat that is perpendicular to its centerline.

- Wheel: The wheel works the rudder, steering the boat.

- Winch: Winches help tighten the sheets and halyards. When these lines are wrapped around a winch (in a clockwise direction), a sailor can turn the winch with a winch handle, providing mechanical advantage which makes it easier to bring in the lines.

-

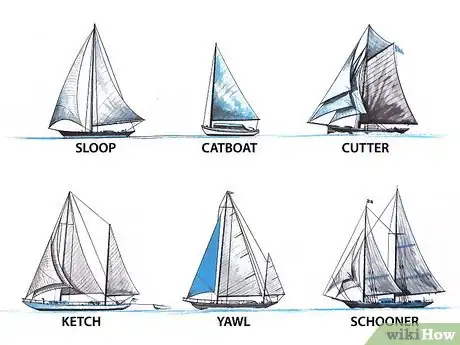

2Know about the different kinds of sailboats. In general, if you are a beginning sailor you will most likely not be operating your own schooner. You will probably be working with a catboat, cutter, or sloop.[2]

- Sloop: Sloops are the most common type of sailboat (when you think of a sailboat this is probably the one you picture in your mind.) It has a single mast and is rigged up with a jib in the front and a mainsail attached to the back of the mast. They can range in size and are ideal for sailing upwind.

- Catboat: A Catboat has a mast set up near the front of the boat and is a single-sail boat. They are small (or large, for that matter) and easily operated by one or two people.

- Cutter: Cutters have one mast with two sails in the front and a mainsail on the back of the mast. These boats are meant for small crews or groups of people and can be handled relatively easily.

- Ketch: A Ketch has two masts, with the second mast called the mizzen mast. The mizzen is shorter than the mainmast and is in front of the rudder.

- Yawl: Yawls are similar to ketches with the difference being that their mizzen masts are located behind the rudder. The reason for this placement is that the mizzen on yawls is for keeping balance, rather than for moving the boat forward.

- Schooner: Schooners are large sailboats with two or more masts. The mast in the back of the boat is either taller or equal in height to the mast at the front of the ship. Schooners have been used to commercially fish, transport goods and as warships.

Advertisement -

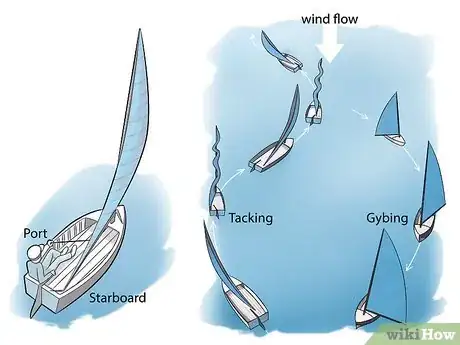

3Know common terms used on a sailboat. Aside from the terms used for the different parts of the boat, there are also certain terms that sailors commonly use while at sea (or heading out to sea.) A trick to remember that port is left and starboard is right is that starboard has two ‘Rs’ in it, which is the beginning letter of ‘right’. Starboard, green and right have more letters than port, red and left. You can also keep in mind that "port wine is red". [3]

- Port: When you are facing the bow (the front of the boat) the side to your left is the port side.

- Starboard: Starboard is the right side of the boat when facing the bow.

- Windward: As the name might imply, windward is the direction from which the wind is blowing, upwind.

- Leeward: This is also called ‘Lee’. This is the direction to which the wind is blowing, downwind.

- Tacking: Tacking is when you turn the bow of the boat through the wind so that the wind switches from one side of the boat to the other. This is when you most need to be mindful of the boom, as the boom will swing from one side of the boat to the other when you tack (you don’t want to be in its way when it does that.)

- Gybing (Jibing): This is the opposite of tacking, which means that it is when you turn the stern (or back) of the boat through the wind so that wind shifts to the other side of the boat. This is a more dangerous maneuver in a strong breeze than tacking since the boat's sails are always fully powered by the wind, and may react violently to the change in the orientation of the boat to the wind. Care must be exercised to control the boom during this maneuver as serious injury is a possibility if the boom travels across the cockpit uncontrolled.

- Luffing: This is when the sails begin to flap and lose drive caused by steering the boat into wind or easing (loosening) sheets.

-

4Understand navigational buoys. It is important to look out for and honor navigational buoys--they'll let you know where the safe water exists. In North America, on your way out of the marina, red buoys are almost always left to port while green buoys are left to starboard. (Remember, Red-Right-Returning). For most of the rest of the world, this is the other way round.[4]

Preparing The Boat

-

1Perform a detailed visual check. Inspect all the standing rigging—the cables and ropes that support the mast—including the turnbuckles and cotter pins securing the rigging to the hull. Many sailboats have dismasted because a 15-cent cotter pin was missing! Sailing instructor Nitzan Levy advises "checking the condition of the sail, as well. It should be straight and white, not worn out, wrinkled, or frayed at the edges."

- Check the lines (running rigging) that raise and control the sails (halyards and sheets respectively). Make sure that they are separated, not wrapped around each other or fouled on anything else, and that they all have a figure-eight knot or other stopper knot on the free (bitter) end so they cannot pull through the mast or sheaves.

- Pull all lines out of their cleats and off their winches. There should be nothing binding any line; all should be free to move and be clear at this point.

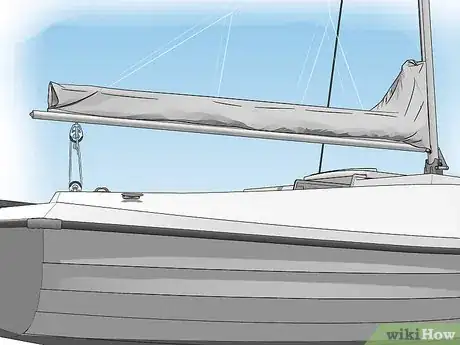

- If you have a topping lift—a small line that holds the back of the boom up and out of the way when the sail isn't in use—let it out until the boom sags downward freely, then re-tie or re-cleat it. Watch out for the boom; it's just swinging around at this point; it will cause a painful "clunk" if it happens to hit you or your crew. The boom will return to its normal, horizontal position when you hoist the mainsail completely.

- If so equipped, be sure that the tiller is properly attached to and controls the rudder. Your sailboat is now prepared for you to hoist the sails!

-

2Determine the wind direction. According to sailing instructor Nitzan Levy, "Many boats have a Windex, or a wind direction indicator, at the top of the mast. You might also see flags on the point, and you can judge the wind based on the way the flags are flying." Levy reassures that "with experience, you'll be able to tell the direction of the wind just by feeling it on your face."

- If your boat doesn't have a windex, tie a couple of nine-inch pieces of old cassette tape, VHS tape, or oiled yarn to the shrouds—the rigging cables that hold up the mast. Place them on each side, about four feet up from the sides of the boat. These will show you from which direction the wind is blowing, although some sailors find cassette tape to be just too sensitive for this purpose.

-

3Point the boat into the wind. The idea is to have the minimum amount of wind resistance when raising the sail, with the sail straight back. In this position, the sail won't be snagging on any shrouds or any other hardware, either. This isn't always easy. The boat won't turn readily because it's not moving (under way). Do the best you can, but be prepared to work for it!

- If your boat has a motor, use the motor to keep the boat pointed into the wind while you hoist sail.

- Here's a handy tip: if the water is not deep at your dock, or if you have no side pier, walk the boat out away from the dock and anchor it into the sand, and the boat will automatically point itself into the direction of the wind!

Hoisting The Sails

-

1Attach the sails. Secure the bottom front (tack) of the mainsail and jib to their respective shackles on the boom and the bow of the boat.

- There will be a small line (outhaul) attaching the rear corner of the mainsail (clew) to the end of the boom. Pull it so the foot of the main is taut, and cleat. This helps the mainsail have a smooth shape for the air flowing over it.

- Hoist the mainsail by pulling down on its halyard until it stops. It will be flapping around (luffing) like crazy, but that's OK for a short period of time. (Excessive luffing will drastically reduce the life and durability of the sail).

- The leading edge of the sail (luff) must be tight enough to remove folds, but not so tight as to create vertical creases in the sail.

- There will be a cleat in the vicinity of the halyard where it comes down from the top of the mast. Cleat the halyard. Using the jib halyard, raise the front sail (jib, genoa or simply the headsail), and cleat the halyard off. Both sails will be luffing freely now. Sails are always raised mainsail first, then the jib, because it's easier to point the boat into the wind using the main.

-

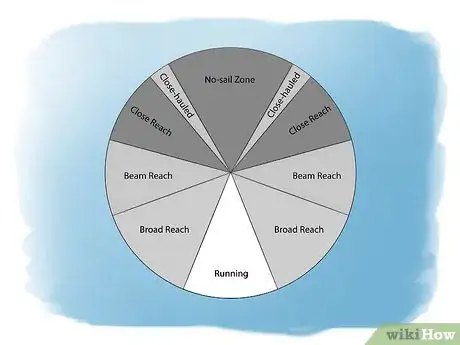

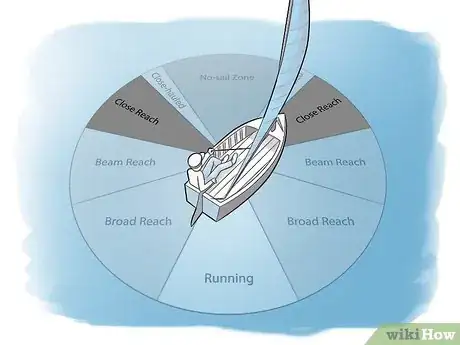

2Adjust your heading and sail trim for the wind. Sailboats cannot sail directly into the wind. As shown above, the red zone in the diagram indicates a "no go" zone when under sail. To sail to windward, a sailing vessel must sail about 45-50 degrees off the wind and change direction by tacking (or zig-zag).

- Turn the boat to the left (port) or right (starboard) so it's about 90 degrees off the wind. This is known as a beam reach.

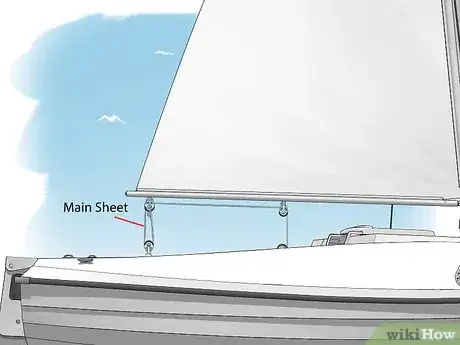

- Pull on the main sheet (trimming) until the sail is around 45 degrees away from straight back (aft). This is a safe place for the main while you trim the jib.

- You will start moving and tilting (heeling) away from the wind. A heel of more than 20 degrees usually indicates that you're being overpowered. Releasing the mainsheet momentarily (breaking the main) will lessen the amount of heel, and you will return to a more comfortable sailing angle of 10 to 15 degrees.

-

3Trim the jib sheets. Although the mainsail is hoisted first, it is the jib that is trimmed first. There are two jib sheets, one for each side of the boat. Pull on the jib sheet on the side away from the wind (leeward side). This is the active sheet while the other is called the lazy sheet.

- The jib will form a curve or pocket; trim the sail until the front edge just stops luffing. Keep your hand on the tiller (or helm) and stay on course!

-

4Trim the mainsail. Let out the main sheet until the front edge just starts to luff, then pull it back just until it stops.

- If you or the wind hasn't changed direction, this is the most efficient place to set the sails. If anything changes, you have to adjust them in response.

- You have just entered the world of the sailor, and you will have to learn to do many things at once, or suffer the consequences.

Sailing Your Boat

-

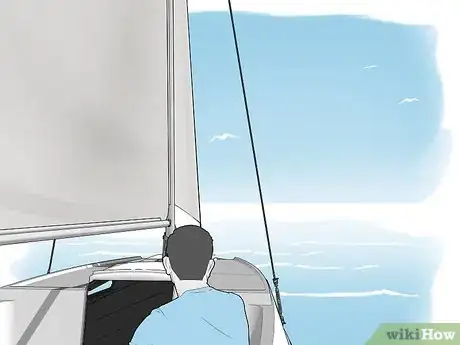

1Watch the front of the sail edge on the main and jib. If it starts to luff, you have two choices: tighten the sail sheet until it stops luffing, or steer away from the wind (bear off). When the sail luffs, it means that you are heading too much into the wind for your current sail setting. If you bear off slightly, (away from the wind) your sails will stop luffing.[5]

-

2Watch your wind indicators (telltales). If you see it change so that the wind is coming from a direction that is more behind you, you will be wasting energy. Let out the sail until it is perpendicular to the wind. You will be constantly watching the sails, the telltales, and trimming sails because the wind won't blow from a constant direction for long.

- When the wind is at your back and side (aft quarter), it's called a broad reach. This is the most efficient point of sail as both sails are full of wind and pushing the boat at full force.

- When the wind is at your back, you are running with the wind. This is not as efficient as reaching, because air moving over the sail generates lift and more force than just the wind pushing the boat.

- When running with the wind, you can pull the jib over to the other side of the boat where it will fill. This is called wing-on-wing, and you have to maintain a steady hand on the tiller to keep this sail configuration. Some boats have a "whisker pole" which attaches to the front of the mast and the clew of the jib which makes the jib much easier to control and keep full of wind. Be sure to be vigilant of obstacles and other vessels, as having both sails in front of you blocks a significant portion of your view.

- Be careful—when the boat is running, the sails will be way off to the side, and because the wind is basically behind you the boom can change sides suddenly (jibe or gybe), coming across the cockpit with quite a bit of force.

- If you have a wind direction indicator at the top of your mast, do not sail downwind (run) so that the wind indicator points toward the mainsail. If it does, you are sailing with the boom on the windward side (sailing by the lee) and are at high risk of an accidental jibe. When this happens the boom can hit you with enough force to knock you unconscious and out of the boat (overboard).

- It's a good practice to rig a preventer (a line from the boom to the toe rail or any available cleat) to limit the travel of the boom across the cockpit in case of an accidental gybe.

-

3Close reach. Turn the boat slightly into the wind ("head up") so your heading is about 60-75 degrees off the wind. You will have to trim in the sheets tighter so the sails are more closely in line with the boat. This is called a close reach. Your sails are acting like the airfoil of an airplane: the wind is pulling the boat instead of pushing it.

-

4Close haul. Continue to turn into the wind (head up) and tighten the sheets until you can go no farther (the jib should never touch the spreaders on the mast). This is called close-hauled, and is as close as you can sail into the wind (about 45-60 degrees off the wind). On a gusty day, you will have all kinds of fun with this point of sail!

-

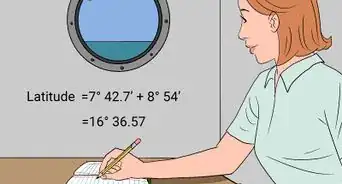

5Sail into the wind to an upwind destination. Sailing instructor Nitzan Levy explains that "you can't sail directly into the wind—you have to maintain a certain angle in order to move forward." Sail a heading that is close to upwind in the direction of your destination with good speed, a close reach. Close-hauled will be the main and foresail pulled tight along the boat centerline and will allow the boat to sail closest to directly upwind, but speed will be smaller.[6]

- On most sailboats this will be about 45 degrees from the wind direction.

- When you've gone as far as you can on this tack, turn the boat through the wind (or changing direction by tacking), releasing the jib sheet out of its cleat or off the winch drum as the front of the boat (bow) turns through the wind.

- The main and boom will come across the boat. The mainsail will self-set on the other side, but you will have to quickly pull in the jib sheet on the now downwind side to its cleat or winch, while steering the boat so the mainsail fills and begins to draw again.

- If you do this correctly, the boat won't slow down much and you will be sailing to windward in the other direction. If you're too slow tightening the jibsheet again and the boat bears off the wind too much, don't panic. The boat will be pushed sideways a little until it gains speed.

- Another scenario would be to fail to put the bow of your boat through the wind quickly enough and the boat comes to a complete stop. This is known as being in irons, which is embarrassing, but every sailor has experienced it, whether or not they'll admit it is another story. Being in irons is easily remedied: when the boat is blown backwards you will be able to steer, and as the bow is pushed off the wind you will achieve an appropriate angle to the wind to sail.

- Point the tiller in the direction you wish to go and tighten the jib sheet to windward, (backwinding the sail). The wind will push the bow through the wind. Once you've completed your tack, release the sheet from the winch on the windward side and pull in the sheet to leeward and you'll be on your way again.

- Because speed is so easily lost when tacking, you'll want to perform this maneuver as smoothly and quickly as possible. Keep tacking back and forth until you get to your destination.

-

6Go easy when learning. Understand that it's best to practice on calm days, and so, for example, learn to reef your boat (make the sails smaller). You will need to do this when the wind is too strong and you're being overpowered.

- Reefing almost always needs to be done before you think you need to!

- It's also a good idea to practice capsize procedures on a calm day too. Knowing how to right your boat is a necessary skill.

-

7Sail safely. Remember that your anchor and its chain/line (rode) are important pieces of safety gear and can be used to stop your boat from going aground or can even be used to get the vessel floating again should a grounding occur.

Storing the Sails

-

1Lower and store your sails. Once you are safely at port, lower your sails by removing the tension from any of the lines, "halyards", holding the sails up. Once you have lowered your mainsail, it may be neatly "flaked" and secured to the boom with several ties, then covered. When your sails are not in use for a significant amount of time, they should be loosely folded and placed in their sail bags. You may need to do this for both your mainsail and the jib. Remove all sail battens from their pockets before folding the main. Do not fold your sails the same way every time or they will develop deep creases that will not be shaken out by the wind. Your sails should be stored when they are dry and mostly salt-free, as wet sails that are stored are generally inclined to grow mildew.

-

2Clean anything else that may have come out of place. Secure lines by tying them to cleats. Neatly wrap all loose lines up and secure them with ties, out of the way of anyone walking around on the deck. Wash the deck of salt, particularly if you have a teak deck. Salt can leave stains on the wood.

Community Q&A

-

QuestionWhat's a tiller, and what does it mean to lower and higher the ropes?

Community AnswerThe tiller is a short pole or a bar that is connected to the rudder or rudders to steer.

Community AnswerThe tiller is a short pole or a bar that is connected to the rudder or rudders to steer. -

QuestionThis sounds hard and complex, how long would it take me to learn to sail from scratch roughly?

Community AnswerYou can learn to sail single and small-capacity boats in a couple days. If you have someone experienced to teach you, the process goes rather quickly. It seems like there's a lot to remember, but it's a lot about feeling the wind and trial-and-error until you get moving. If you practice on a fairly calm day on a lake where you won't get huge waves, you'll be skippering your friends around in no time.

Community AnswerYou can learn to sail single and small-capacity boats in a couple days. If you have someone experienced to teach you, the process goes rather quickly. It seems like there's a lot to remember, but it's a lot about feeling the wind and trial-and-error until you get moving. If you practice on a fairly calm day on a lake where you won't get huge waves, you'll be skippering your friends around in no time. -

QuestionHow do I speed up and slow down?

Community AnswerWhen you want to go fast, try to angle the boat to pick up as much wind as possible. If you want to slow down, reef the sails.

Community AnswerWhen you want to go fast, try to angle the boat to pick up as much wind as possible. If you want to slow down, reef the sails.

Warnings

- Going overboard is a serious matter, especially if you are alone. Cold water, currents, and other boats all can account for serious dangers, and if the sails are up, the boat will take off much faster than you might expect. Additionally, many boats float so high on the water (freeboard) that it is difficult to climb in or haul people in without assistance. When sailing at night, always wear a shoulder-mounted flashlight and strobe emergency signaling device, which makes it much easier for a SAR (Search And Rescue) crew to spot you in the water.⧼thumbs_response⧽

- In sailing, your very life may depend on doing things before they need to be done, when they first cross your mind. If you wait until it needs to be done, it may be too late or very difficult. Follow your instincts.⧼thumbs_response⧽

- Remember the old maxim "It's better to be on the dock, wishing you were on the lake, than to be on the lake, wishing you were on the dock". Don't let enthusiasm overcome your good judgement on a day you should not go out. The apparent wind while tied alongside at the dock may be very different out on the water. Many novices (and experienced sailors, for that matter) get into trouble venturing out when there is too much wind to sail safely.⧼thumbs_response⧽

- It is highly recommended that you at least have working knowledge of the nomenclature of the boat and have done some reading of in-depth material before attempting this sport yourself. Some highly recommended reads are: The Complete Idiot's Guide to Sailing, Sailing for Dummies, and Sailing the Annapolis Way by Captain Ernie Barta.⧼thumbs_response⧽

- Know how how to use VHF radio to make a Mayday call from a Marine Vessel. In an emergency, it is usually the quickest way to summon help. Cell phones may be used, but VHF will be able to contact a nearby vessel much more quickly should you need assistance or be able to render same.[9]⧼thumbs_response⧽

Things You'll Need

- A life vest (Personal Flotation Device) is mandatory on all boats for all passengers. (A pealess whistle attached to the PFD is an excellent idea!) You should wear one at all times. If you have children with you, they should wear one even when you are at the dock.

- Every vessel, regardless of length is required to have a certain amount of safety gear aboard. This ranges from an anchor with sufficient rode, flares, and other equipment as may be mandated by the Government. These regulations are for your safety and should be adhered to.

References

- ↑ http://www.lovesailing.net/sailing-theory/sailing-basics/parts-of-a-boat/parts-of-a-boat.php

- ↑ https://www.boats.com/resources/sailing-101-sailboat-types-rigs-and-definitions/

- ↑ http://www.discoverboating.com/resources/article.aspx?id=243

- ↑ https://www.uscgboating.org/images/486.PDF

- ↑ https://www.cruisingworld.com/learn-to-sail-101#page-2

- ↑ https://www.discoverboating.com/resources/how-does-a-boat-sail-upwind

- ↑ https://www.dummies.com/sports/sailing/finding-the-winds-direction/

- ↑ https://weather.com/news/news/read-clouds-meteorologist-20130826

- ↑ https://www.boatus.org/marine-communications/basics/

About This Article

To sail a boat, start by performing a detailed visual check of the cables and ropes that support the mast. Next, determine the wind direction by referring to the wind direction indicator at the top of the mast, then point the boat into the wind. Secure the bottom front of the mainsail and jib to the shackles on the boom and bow of the boat, then trim the jib sheets and mainsail before letting out the main sheet! For tips on monitoring wind indicators, read on!