This article was co-authored by Matthew Snipp, PhD. C. Matthew Snipp is the Burnet C. and Mildred Finley Wohlford Professor of Humanities and Sciences in the Department of Sociology at Stanford University. He is also the Director for the Institute for Research in the Social Science’s Secure Data Center. He has been a Research Fellow at the U.S. Bureau of the Census and a Fellow at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences. He has published 3 books and over 70 articles and book chapters on demography, economic development, poverty and unemployment. He is also currently serving on the National Institute of Child Health and Development’s Population Science Subcommittee. He holds a Ph.D. in Sociology from the University of Wisconsin—Madison.

This article has been viewed 21,985 times.

Beginning a research project or paper can be intimidating if you’ve never conducted any research before. However, doing research is a valuable skill. As you learn to research, you will also learn how to evaluate sources, organize data, and provide citations. These skills will be useful throughout your academic career. Note: if you want to learn about doing scientific research, you can find that information here.

Steps

Planning Your Research

-

1Understand your assignment. It is important, with any assignment, to understand fully what is expected of you before you start. Be sure that you know the details of your instructor’s expectations for the research process and the resulting product. If you have a printout with assignment details on it, keep it with you while you work and reread it occasionally to be sure that you are staying on track. A few questions to ask or keep in mind about your research follow:

- How many sources are expected or required?

- Is the final project a paper or a multimodal (creative) project?

- How long should your final product be?

- Are there minimums for the types of sources (ie: print versus web-based)?

- How long do you have to work on your research?

- What resources are available for you to conduct your research (for example, customized databases, reserved library books, etc)?

-

2Choose a topic. Consider yourself lucky if you are assigned a topic; you can skip this step! In some ways, determining what topic to research can be the most difficult part of your project.[1] It’s often best to select something that you already have some interest in and at least a cursory knowledge about, but not something that you are so passionate about that you may find it difficult to be objective.[2]

- Many instructors will provide you with a list to choose a topic from: if you have such a list, circle 3-5 topics that jump out at you. If you have time, look them up online and see if you feel genuinely curious about one of the topics. Rank your top 5, as you may not be able to use your first choices if others in your class have already “claimed” them.

- If your topic selection is wide-open, brainstorm a list of potential topics within the parameters of the assignment. If you are not given parameters, you may have to come up with them on your own; you can assume, for example, that if you’re in a biology class, your research topic will have to do with biology. If you are assigned parameters, such as “research an endangered species,” you should be able to find a list and select a specific animal, such as the cheetah.

Advertisement -

3Determine the purpose of your research project. The outcome of your final research project will partially determine the depth and breadth of your research. It is important to know ahead of time whether the purpose of the project is to convey information, make a persuasive argument, or present differing viewpoints about an issue.[3]

- If the research project is simply a factual report about an endangered species, you will want to present as much information as you can about the animal, its habitat, and influences on its livelihood.

- If your research project is an essay about a controversial topic, you’re likely to need to take a position and persuade your audience towards your position. For example, an essay about the effectiveness of juvenile imprisonment would likely require you to take a position on the issue.

-

4Limit the focus of your topic. It is important that you limit your project to an appropriate scope before you begin.[4] If your instructor has provided a list of topics, she has likely already considered appropriate scope. However, if you are selecting a topic, you will need to find a balance between broad and specific that is appropriate to the length of your final project.

- For example, the topic “imprisonment in the US” is extremely broad, as it covers a range of issues and life stages as well as a large geographical area. Instead, limiting the scope of your research to “juvenile imprisonment,” “post-prison reintegration into society,” or “prison conditions at Rikers Island in NY” will lead to a more focused project.

-

5Develop a research question. It may be helpful to have a central question that guides your research. You could even write the question on an index card and keep it with you while you research. Revisiting your research question while you are working will help keep your research focused and may cut down on wasted time.

- For example, your research question for the cheetah as an endangered species could be either “why is the cheetah endangered?” or “how can we save the cheetah?”

- For example, your research question for an essay about juvenile imprisonment could be “is juvenile imprisonment effective?” or “what is a more effective solution to juvenile delinquency than imprisonment?”

-

6Set a research schedule. Research projects often take more time than you expect them to, and they are quite difficult to do at the last minute. To make a research schedule, begin with your final project due date and work backwards, setting dates for yourself for your rough draft, your prewriting, your research organization, conducting your research, and selecting and limiting your topic. Be sure to plan adequate time outside of your home, working at your school or public library.

-

7Talk to your teacher or a librarian. If you are having trouble choosing a topic, limiting your topic, or developing a research question, try talking to your instructor or a school or public librarian. These individuals are trained to assist students do research, and they can help guide you to find a topic that you will enjoy researching that will produce a successful paper or project.

- It is best to talk to your teacher early in the research process, soon after the project is assigned. If you were given 2 months to work on a research project and you wait until the week before it is due to approach her, she may not be as enthusiastic about helping you select a topic.

Conducting Research

-

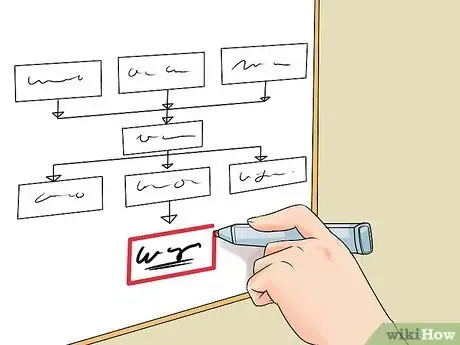

1Select your research key words. This may seem like an obvious step, but you will need to choose the words that you use to research. To do this, brainstorm a list of words that are related to your topic. You may find that you need to revise your search terms as you progress.

- If you are searching for sources about the endangered species cheetah, your search terms may be “cheetah,” “endangered,” “habitat,” “climate change,” “grasslands,” “fur trade,” and “conservation.”

- If you are searching for sources about juvenile imprisonment, your search terms may be “juvenile,” “youth,” “imprisonment,” “prisons,” “juvenile delinquency,” “effectiveness of imprisonment,” and “detention.”

-

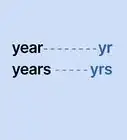

2Use Boolean operators. Boolean operators are words that function as limiting commands. They give you the ability to combine keywords and limit your search. The most common Boolean terms are AND, OR, and NOT. Another common Boolean limiter is to place quotation marks around exact phrases.[5]

- For example “juvenile detention” (with quotation marks) would give you sources that use the terms together as a phrase, while juvenile detention (without quotation marks) would yield results for both “juvenile” and “detention” separately.

- For example, you may want to search prisons AND juvenile to ensure sources talk about both terms.

- For example, you may want to search cheetah NOT girls to exclude the Disney movie Cheetah Girls from your search about cheetahs.

-

3Find the research resources available to you. Many instructors and librarians will compile research resources for a particular research project. There may be a customized database on your library’s webpage that automatically limits your search to pre-approved sources, or your librarian may have set aside a cart of printed books that will be reserved in the library for the duration of the research project. These types of customized resources will save you time and make your research process easier.[6]

- If customized research aids are not available, you should still consult the library’s databases. Often, the sources in the databases are legitimate academic sources that are appropriate for an academic assignment.

-

4Avoid common search engines. As tempting as it can be to open up your favorite search engine and look up your research keywords, this shouldn’t be your first stop for research. If you use a common search engine, you will have to evaluate the legitimacy of each source you find, and you will have to sort through many, many pages of often irrelevant search materials.

- Common search engines use some limiters, but often the Boolean operators do not work effectively.

-

5Ask for help from a research assistant. If you feel overwhelmed by starting your research project, talk to a librarian who specializes in research assistance. Remember that you are not bothering them; it’s their job to help students research!

- Ask for a few specific starting points (don’t let them overwhelm you further with a long list of research sources) and let your research “snowball” on its own.

- You’re likely to find that once you get started, it will become easier to find and evaluate sources, find the research you need, and move forward with your research project.

-

6Take thorough notes. Now that you have started to research, you need to collect the information. As you read sources, collect notes from the source. You can either take direct quotes from the source (word-for-word; indicate that the information is a direct quote by putting quotation marks around it) or you can paraphrase the information (put it in your own words). Either way, you will need to keep track of and cite the source.

- You can take notes by hand by putting them in a research notebook or put individual facts on index cards. Be sure to indicate the source when you write the notes; you might want to number your sources and place the number from the source next to the piece of information/research.

- You can also take notes on the computer by copying and pasting source material into a word processing document. Be sure to keep track of what source information came from; you may want to provide a link to a source and a citation, then place research from that source below the citation.

Using Sources Appropriately

-

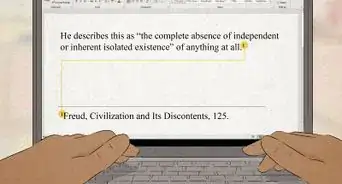

1Do not plagiarize any material. Plagiarizing information, or taking someone else’s writing or information without giving them credit for it, will likely result in (at best) failing the assignment or (at worst) facing disciplinary action and/or failing the course. Always cite any material that does not come out of your own head. This means that much of your work will be cited from other places.

- Some information that is considered common knowledge, like facts that are found in many different sources such as dates of birth scientific names, do not need to be cited. However, when in doubt, cite it out!

-

2Differentiate between primary and secondary sources. Primary sources are sources that come directly from a person. Original writing, interviews, and the first time scientific studies are published all count as primary sources. Secondary sources are sources that write about or analyze the primary sources. Your instructor may specify that you need to include primary as well as secondary sources. Some projects, however, may not require primary source data.

-

3Evaluate the quality of sources.[7] Not all sources are equal in the world of education. The easiest way to find high-quality sources is to search through your library database. If you cannot do that and you need to evaluate the source yourself, ask yourself the following questions:

- Who published the source?

- What seems to be the goal of the publication?

- Is the source objective or academic?

- If an organization produced the source, is it a nonpartisan and fair organization?

- If an individual wrote the source, do they have any credentials listed?

- Some sources to avoid include: blogs (which are almost entirely opinion-based), sites that are trying to sell you something, sites with excessive (and obnoxious) advertisements, and sites from biased or questionable organizations.

- Sources that tend to be better include: government sources, peer-reviewed academic journals, big-name newspaper articles (but not opinion sections or letters to the editor), national nonprofit organizations, university-affiliated sources, and scientific organizations.

-

4Select sources that you understand. Some sources, particularly those printed in academic journals, can be difficult for someone outside the field to understand. This can lead to frustration and confusion on your part, as well as a misuse of information; if you don’t fully understand what is being said, you may use the information improperly.

- Consider using the “five finger test:” go to one page of the source. For each word that you don’t recognize or understand, put a finger up. If you get to all five fingers up before the end of the page, stop and find a new source.

-

5Use a variety of sources. You should use some print sources if possible. Most libraries have high-quality books and reference materials to aid research. Use a few print sources as well as academic database sources. Try not to rely too heavily on one author or organization for your researched information.

-

6Keep a reference page. Also known as a “works cited” page, a reference page is essentially a list of the sources you used for research. Do not wait until you have finished the research project to compile the reference page; have a working reference page as you do your research, and finalize it before you turn it in.

- Be sure that you format your reference page in the appropriate style. If your assignment does not specify, ask your teacher or librarian which style would be appropriate for the subject area.

Organizing the Research

-

1Divide your research items. It’s important to keep track of which research comes from which source, but you may also want to be able to physically move around your research. If you can “tag” each piece of research with its source (ie: by providing a source number or writing the last name of the author of the source next to each piece of research), you will have the flexibility to cut and paste the pieces of research so that you can group the research items into what will become sections of your project. Some ways you can cut and paste your

- Write your information on index cards, with one fact or quotation on each card.[8]

- Type information and quotations on separate lines in a word processing program so that you can move the items around.

- Print out your typed research and physically cut each piece of research into strips that you can move around.

-

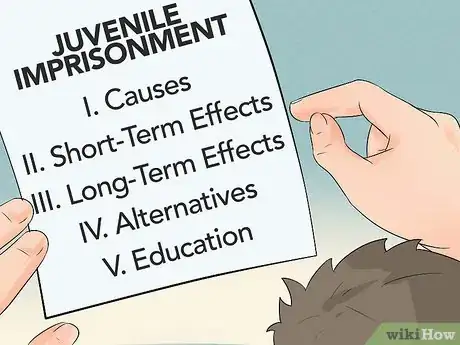

2Group your research items. Once you have the flexibility of being able to move the research items physically or within a word processing program, group items together into what will become sections of your paper or project.

- For example, if you are writing about juvenile imprisonment, you may group your information into “causes,” “short-term effects,” “long-term effects,” “alternatives,” and “education.”

- For example, a research project on cheetahs may be grouped into “habitat change,” “species information,” “conservation efforts,” and “future predictions.”

-

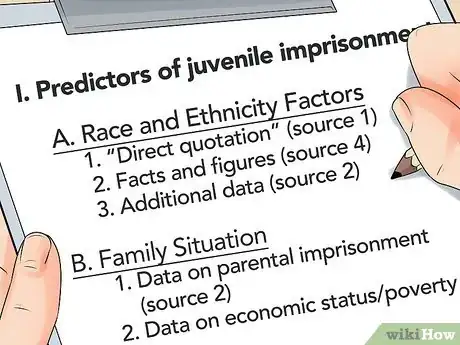

3Write an outline. One of the best ways of preparing to convert your disparate research into a more cohesive final project (particularly a paper) is to write an outline. With an outline, you will create several main topics (usually indicated by roman numerals), followed by sub-topics (indicated by uppercase letters), and then sub-sub topics (indicated by numbers). An outline can help you organize your research, reveal places that are unbalanced and need more or less research, and prepare you to begin writing.[9] An example for an outline may be:

- I. Predictors of juvenile imprisonment.

- A. Race and Ethnicity Factors

- 1. “Direct quotation” (source 1)

- 2. Facts and figures (source 4)

- 3. Additional data (source 2)

- B. Family Situation

- 1. Data on parental imprisonment (source 2)

- 2. Data on economic status/poverty (sources 3 and 4)

- A. Race and Ethnicity Factors

- Note: the numbered sections in the example above would be your actual research items from your index cards or other research method.

- I. Predictors of juvenile imprisonment.

-

4Begin to write. Now that you have conducted and organized your research, you should be ready to compile it in the form of an essay or project. Be sure you include source citations in the proper format as you write, and don’t be afraid to go back and conduct more research if you feel like you have a weak section or missing information.[10]

Expert Q&A

-

QuestionAre surveys a good way to collect data?

Matthew Snipp, PhDC. Matthew Snipp is the Burnet C. and Mildred Finley Wohlford Professor of Humanities and Sciences in the Department of Sociology at Stanford University. He is also the Director for the Institute for Research in the Social Science’s Secure Data Center. He has been a Research Fellow at the U.S. Bureau of the Census and a Fellow at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences. He has published 3 books and over 70 articles and book chapters on demography, economic development, poverty and unemployment. He is also currently serving on the National Institute of Child Health and Development’s Population Science Subcommittee. He holds a Ph.D. in Sociology from the University of Wisconsin—Madison.

Matthew Snipp, PhDC. Matthew Snipp is the Burnet C. and Mildred Finley Wohlford Professor of Humanities and Sciences in the Department of Sociology at Stanford University. He is also the Director for the Institute for Research in the Social Science’s Secure Data Center. He has been a Research Fellow at the U.S. Bureau of the Census and a Fellow at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences. He has published 3 books and over 70 articles and book chapters on demography, economic development, poverty and unemployment. He is also currently serving on the National Institute of Child Health and Development’s Population Science Subcommittee. He holds a Ph.D. in Sociology from the University of Wisconsin—Madison.

Research Fellow, U.S. Bureau of the Census If it's just a school assignment, this is a perfectly reasonable way to go about collecting data for yourself. For larger projects, people have been really struggling with survey response rates the last 20 years or so. People just seem to be less likely to turn in surveys than they used to be; and it's an issue that researchers are definitely trying to solve. With that said, if you can collect a meaningful number of data points, it's definitely not a bad way to go about collecting info.

If it's just a school assignment, this is a perfectly reasonable way to go about collecting data for yourself. For larger projects, people have been really struggling with survey response rates the last 20 years or so. People just seem to be less likely to turn in surveys than they used to be; and it's an issue that researchers are definitely trying to solve. With that said, if you can collect a meaningful number of data points, it's definitely not a bad way to go about collecting info. -

QuestionWhere can you find data if you don't collect it yourself?

Matthew Snipp, PhDC. Matthew Snipp is the Burnet C. and Mildred Finley Wohlford Professor of Humanities and Sciences in the Department of Sociology at Stanford University. He is also the Director for the Institute for Research in the Social Science’s Secure Data Center. He has been a Research Fellow at the U.S. Bureau of the Census and a Fellow at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences. He has published 3 books and over 70 articles and book chapters on demography, economic development, poverty and unemployment. He is also currently serving on the National Institute of Child Health and Development’s Population Science Subcommittee. He holds a Ph.D. in Sociology from the University of Wisconsin—Madison.

Matthew Snipp, PhDC. Matthew Snipp is the Burnet C. and Mildred Finley Wohlford Professor of Humanities and Sciences in the Department of Sociology at Stanford University. He is also the Director for the Institute for Research in the Social Science’s Secure Data Center. He has been a Research Fellow at the U.S. Bureau of the Census and a Fellow at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences. He has published 3 books and over 70 articles and book chapters on demography, economic development, poverty and unemployment. He is also currently serving on the National Institute of Child Health and Development’s Population Science Subcommittee. He holds a Ph.D. in Sociology from the University of Wisconsin—Madison.

Research Fellow, U.S. Bureau of the Census Look at data that's already been collected and sorted! For example, researchers these days will reach out to the big the big social media companies, like Facebook and Twitter. They collect a ton of information and data on their users. It's not a nefarious thing, it's just a normal part of running a tech company, but that data can be extremely useful for research purposes.

Look at data that's already been collected and sorted! For example, researchers these days will reach out to the big the big social media companies, like Facebook and Twitter. They collect a ton of information and data on their users. It's not a nefarious thing, it's just a normal part of running a tech company, but that data can be extremely useful for research purposes. -

QuestionHow do I know what to write about in a research paper?

Matthew Snipp, PhDC. Matthew Snipp is the Burnet C. and Mildred Finley Wohlford Professor of Humanities and Sciences in the Department of Sociology at Stanford University. He is also the Director for the Institute for Research in the Social Science’s Secure Data Center. He has been a Research Fellow at the U.S. Bureau of the Census and a Fellow at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences. He has published 3 books and over 70 articles and book chapters on demography, economic development, poverty and unemployment. He is also currently serving on the National Institute of Child Health and Development’s Population Science Subcommittee. He holds a Ph.D. in Sociology from the University of Wisconsin—Madison.

Matthew Snipp, PhDC. Matthew Snipp is the Burnet C. and Mildred Finley Wohlford Professor of Humanities and Sciences in the Department of Sociology at Stanford University. He is also the Director for the Institute for Research in the Social Science’s Secure Data Center. He has been a Research Fellow at the U.S. Bureau of the Census and a Fellow at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences. He has published 3 books and over 70 articles and book chapters on demography, economic development, poverty and unemployment. He is also currently serving on the National Institute of Child Health and Development’s Population Science Subcommittee. He holds a Ph.D. in Sociology from the University of Wisconsin—Madison.

Research Fellow, U.S. Bureau of the Census You really have to narrow in on a single query and figure out what kind of information would absolutely need to be covered for that question to be adequately answered. You also have to ask yourself, "What is this paper not going to cover?" I think for a lot of people, that's actually the harder question. It's really easy to kind of go off of the rails when you're dealing with a big research question, so staying focused is key.

You really have to narrow in on a single query and figure out what kind of information would absolutely need to be covered for that question to be adequately answered. You also have to ask yourself, "What is this paper not going to cover?" I think for a lot of people, that's actually the harder question. It's really easy to kind of go off of the rails when you're dealing with a big research question, so staying focused is key.

References

- ↑ https://libguides.umflint.edu/research/topic

- ↑ Matthew Snipp, PhD. Sociology Professor, Stanford University. Expert Interview. 26 March 2020.

- ↑ Matthew Snipp, PhD. Sociology Professor, Stanford University. Expert Interview. 26 March 2020.

- ↑ https://libguides.mit.edu/select-topic

- ↑ https://guides.lib.berkeley.edu/evaluating-resources

- ↑ Matthew Snipp, PhD. Sociology Professor, Stanford University. Expert Interview. 26 March 2020.

- ↑ https://libguides.furman.edu/special-collections/for-students/primary-secondary-sources

- ↑ https://library.sacredheart.edu/c.php?g=29803&p=185933

- ↑ https://academics.umw.edu/writing-fredericksburg/files/2011/09/Basic-Outlines.pdf

- ↑ Matthew Snipp, PhD. Sociology Professor, Stanford University. Expert Interview. 26 March 2020.

About This Article

If you need to research a certain topic, write down several keywords that relate to your chosen topic. Visit the library and use their database to search for reliable sources, including scholarly articles, reference books, and historical information relating to your topic or keywords. Your school may also have a special search engine for research that you can use, so ask your teacher. Once you’ve collected a few sources, read through them carefully, taking thorough notes that you can reference later. Be sure to write down all the information you’ll need to cite your source if you use it in your final paper! Read on for tips on organizing your research into an outline!

-Step-17.webp)