This article was co-authored by Paul Chernyak, LPC. Paul Chernyak is a Licensed Professional Counselor in Chicago. He graduated from the American School of Professional Psychology in 2011.

There are 12 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page.

This article has been viewed 31,520 times.

Although self-injury is frequently seen as a risk factor for suicidal ideations and/or behavior, many teens and young adults engage in self-harm out of a need to cope with painful or confusing emotions rather than a desire to take their own lives. Self-injury is a serious and potentially life-threatening issue. Studies suggest as much as 13 to 23 percent of adolescents in the United States engage in such behaviors.[1] Fortunately, when you work with doctors and mental health providers to figure out the underlying function of the behavior, recovery is possible.

Steps

Investigating Your Reasons for Self-Harm

-

1Accept that you are not alone. Estimates point to nearly two million teens and young adults in America who purposely injure themselves in some way.[2] Statistics show that young women are more likely to self-injure than young men. So, know that if you are a young person who has been hurting yourself, you are not alone. There are many others out there who know what you are going through, and you can get help.

- It might give you hope to visit websites where you can read stories about others who have overcome the urge to self-harm.[3]

-

2Recognize what self-harm is. Self-injury basically means causing harm to oneself on purpose. A common example of self-injury is cutting using a knife, razor, or other sharp object. Other methods may include biting, pinching, burning, hitting, pulling out hair, or picking at wounds. Extreme cases may even result in broken bones.[4]

- People who self-injure often do so in secret. Your friends or family members may be unaware of the signs because self-injurers often wear long sleeves and pants and focus the injuries on hidden areas like the limbs and torso.

-

3Look for triggers. Oftentimes, self-injury is a release for emotional pain. You may not have role models for dealing with feelings like anger, sadness, disappointment, or frustration, or you may have been raised to hide these emotions. The harmful behavior serves as an outlet. In some cases, teens might hurt themselves because they feel numb; they just want to feel something. However, self-harm is generally followed by shame or guilt that leads to more self-injurious behavior, a dangerous and endless cycle.[5]

- Try to pay attention to when you have the urge to harm yourself. What happened before you started cutting, scratching, etc.? What did you feel in your body? What thoughts went through your head? Identifying these triggers can shed insight on how to overcome self-harm when you do seek help.

-

4Know that self-injury can be a symptom of a bigger issue. Research has connect self-jury to psychiatric disorders like eating disorders, borderline personality disorder, depression, anxiety, substance abuse disorder, and developmental disabilities, to name a few.[6]

- You may be struggling with one of these conditions and the self-harm is merely a symptom of a larger problem. However, some adolescents engage in self-harm who do not meet the criteria for any mental disorder.

Getting Help for Self-Harm

-

1Understand why you should stop. The release found from self-harm is short-lived. Soon enough, painful emotions like guilt or shame creep in and prompt the need to self-harm again. This addictive, cycling quality of self-injury is partly why it is so dangerous. You may start to lose control and do more damage than you intended or actually attempt suicide.[7]

- What's more, mental illnesses like eating disorders as well as alcohol and substance abuse may further reduce self-control and intensify the damage of self-injury.[8]

- This behavior can expose you to bigger problems down the line. The only way to overcome self-harm is learn to cope with your emotions.

-

2Confide in someone you trust. The burden of keeping self-harm to yourself can become lonely. Once you accept that you need help, it's important to think about a supportive person who you can talk to. Perhaps you can choose someone with whom you have shared confidential information in the past without the person gossiping or judging you.[9] [10]

- Let your friend know that you need to talk. Try to have such a conversation face-to-face. Explain why you are telling her/him this, how you feel, and allow her/him to process the information. You might say something like this "I have been keeping this secret for a long time and you're the only person I feel comfortable sharing it with. I have been hurting myself. It's getting worse, and I'm scared. Please help me".

-

3Seek help. If you do not have anyone close to confide in, you can talk to your school counselor, a teacher, a coach, a religious leader, a friend's parent, or your family doctor. Any of these individuals should be able to offer you support and refer you to a mental health profession in your area who has experience with self-injury.

-

4Participate in therapy. Once you have identified a therapist who might be a good fit for you, set up an appointment. One type of effective treatment strategy for self-injury is dialectical behavior therapy which focuses on teaching you to regulate your emotions, manage and tolerate life stressors, practice mindfulness, and improve your interpersonal functioning.[11]

- In the first session, you can expect for the therapist to ask you basic questions about your behaviors, thoughts and feelings. He will also try to learn more about you - your life, your school/work, your family, and your background - in order to personalize treatment to fit your unique circumstances.[12]

- Some adolescents may also benefit from taking part in family therapy which strives to identify barriers to your recovery and assists family members with understanding what you are going through and being more supportive.[13]

-

5Join a support group. Feeling disconnected and alone in your suffering is common with self-injury. Getting involved in a local or online support group that enables you to talk with other teens who are going through the same thing can give you hope and make you feel less isolated. One particularly effective support group is called S.A.F.E., which stands for Self-Abuse Finally ends. Find a support group in your area.[14]

Developing Healthy Coping

-

1Strive for emotional awareness. A major hindrance to healthy coping is being unaware of what you're feeling and why. Emotional awareness, or sometimes called emotional intelligence, means you have the ability to identify and manage your emotions. Emotional awareness involves a two-step process: learning to understand your emotions and developing tools to handle them.[15]

- To better understand your emotions, pay attention to how you feel in different circumstances and during different parts of the day.[16] Notice your thoughts, physical sensations, and the urges you have in response to these. Try to label the feeling and then rate how strong each feeling is. For example, if you are going to a friend's party, you might have a slight twinge in your stomach and constantly check the time and worry about the outfit your chose. You might label it as nervous excitement and rate it an 8, because you are happy to go and hoping you have fun.

- Once you become better at identifying emotions, aim to describe what you're feeling to others. This helps you become better at putting emotions into words and connecting with friends, family members, and other in your life. For instance, you might tell your mom "I'm super excited about Jason's party today!"

-

2Create an emotional management/ stress relief toolbox. The second step to greater emotional intelligence is finding ways to manage emotions in a healthy way.[17] Look for other outlets to cope with painful feelings, self-soothe, manage tension or anger, or connect you with others when you feel numb. Replace the previous self-harm objects with the materials you use to cope.[18] Work with your therapist to equip your toolbox with practices that meet the function of your self-harm. Some examples for each category may include:

- To cope with emotional pain or strong feelings: express yourself by writing or journaling; draw or paint in colors that match what you're feeling; listen to music or read poems that describe your feelings; or write about the emotional pain and then tear up the paper

- To relax or soothe yourself: read a book; play with or walk a pet; take a calming bath; give yourself a massage; do a guided imagery exercise; meditate; or cuddle in a warm blanket or comfy clothing

- To manage anger: engage in vigorous exercise (e.g. boxing, swimming, running, etc.); release tension by making noises; scream into a pillow; or squeeze a stress ball or Play-Doh

- To overcome numbness or disconnectedness: call a friend; run ice along your arm; take a cold shower; chew something with intense flavor (e.g. mint leaves, chili peppers, etc.)

-

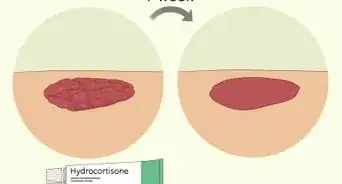

3Push for good physical health. After hurting yourself physically, it can be a healing practice to put effort into taking better care of your body. Make a commitment to eat healthy, balanced meals, sleep 7 to 9 hours each night, and get regular physical activity whether it be walking around your block or participating in sports at school.

- Not only will maintaining physical health help you feel better, but it's a first step in taking charge of loving and caring for yourself again.[19]

-

4Locate a place internally or externally where you feel safe. Having an immediate go-to in the face of an urge to self-harm can keep you on the road to recovery. In addition to any tools in your toolbox, you might also identify a serene place - the more, the better - where you can go to overcome an urge.[20]

- This place can be physical, such as the swing in your backyard or the comfy pouf in the corner of your bedroom. Or, your place can be mental, such as a peaceful meadow or a favorite childhood hiding spot.

Warnings

- Remember that chronic self-injury can lead to seriously endangering your physical health or even a suicide attempt, find the courage to get help for self-harm today.⧼thumbs_response⧽

References

- ↑ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2695720/

- ↑ http://www.mentalhealthamerica.net/self-injury

- ↑ https://www.kidshelpline.com.au/teens/get-info/stories/recovering-from-self-harm/

- ↑ https://www.nami.org/Learn-More/Mental-Health-Conditions/Related-Conditions/Self-harm

- ↑ https://www.nami.org/Learn-More/Mental-Health-Conditions/Related-Conditions/Self-harm

- ↑ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2695720/

- ↑ http://www.mentalhealthamerica.net/self-injury

- ↑ https://www.nami.org/Learn-More/Mental-Health-Conditions/Related-Conditions/Self-harm

- ↑ http://www.selfinjury.bctr.cornell.edu/perch/resources/reaching-out-for-help-pm-5.pdf

- ↑ http://www.helpguide.org/articles/anxiety/cutting-and-self-harm.htm

- ↑ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2695720/

- ↑ http://www.selfinjury.bctr.cornell.edu/perch/resources/therapy-what-to-expect-pm-2.pdf

- ↑ http://www.selfinjury.bctr.cornell.edu/perch/resources/therapy-what-to-expect-pm-2.pdf

- ↑ http://www.selfinjury.com/treatments/focus/

- ↑ http://www.helpguide.org/articles/emotional-health/emotional-intelligence-eq.htm

- ↑ http://kidshealth.org/teen/your_mind/emotions/understand-emotions.html#

- ↑ http://www.helpguide.org/articles/anxiety/cutting-and-self-harm.htm

- ↑ http://www.selfinjury.bctr.cornell.edu/perch/resources/recovering-from-self-injury-1.pdf

- ↑ http://nedic.ca/moving-self-harm-self-care

- ↑ http://www.selfinjury.bctr.cornell.edu/perch/resources/recovering-from-self-injury-1.pdf