wikiHow is a “wiki,” similar to Wikipedia, which means that many of our articles are co-written by multiple authors. To create this article, volunteer authors worked to edit and improve it over time.

There are 11 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page.

This article has been viewed 51,761 times.

Learn more...

Wound granulation tissue otherwise referred to as “fibroplasias” forms at the surface of a wound as the healing process takes place. Granulation may help guide healthcare professionals in monitoring and evaluating the progress of wound healing. Although, it is difficult to accurately measure the granulation tissue, there are some general guidelines to follow.

Steps

Measuring with the Pressure Ulcer Scale for Healing

-

1Assess the surface of the wound. Complete wound assessment should include the history of how the wound was acquired, the anatomic location of the wound and the stage or phase of wound healing.[1]

- It is crucial to note the length, width and depth of the wound in centimeters, in addition to whether the wound is tunneling or undermining. Look for signs of infection such as redness, pain and drainage. Check for necrotic and granulation tissue.

- Necrotic tissues are characterized by reddish brown fragmentation and form thick and leathery black eschar (dead tissue). Oftentimes, this masks an underlying collection of pus or an abscess.

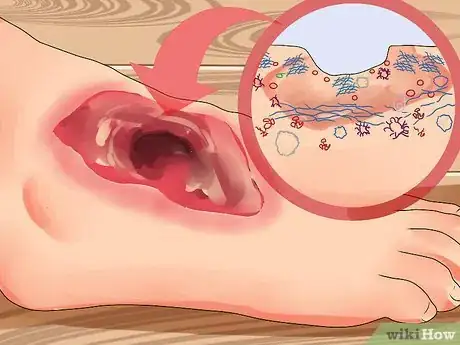

- Meanwhile, healthy granulation tissues appear as shiny, uneven or bumpy, beefy red at the wound base.

-

2Measure the wound surface using the Pressure Ulcer Scale for Healing.[2] Get the length and width of the wound in centimeters, scored at 0 to 10. Take note of any exudates (fluids seeping from the wound) and rate 0 for none down to 3 when exudates are heavy.

- Also document the type of tissue using the 0 to 4 scale rating: 0 for a closed or resurfaced wound, 1 for superficial epithelial tissue, 2 for granulation tissue, 3 for slough tissues characterized by yellow to white tissues with mucous and 4 as a necrotic tissue.

- Get the sum and place it on a graph to monitor any changes or progress in the condition of the wound.

Advertisement -

3Measure the wound depth vs the approximate percentage of wound granulation. Clinicians measure the wound depth using the granulation tissue. A significant decrease in wound depth indicates a remarkable proliferation of granulation tissue. A significant decrease is measured as at least a 0.2 centimeter (0.1 in) change in depth compared to the previous assessment.[3]

-

4Cleanse the wound. First, wash your hands with soap under running water to prevent the spread of bacteria and other microorganisms. Dry your hands with a clean towel. Put on a pair of clean rubber gloves.

- Remove the soiled wound dressing and dispose of it properly. Dress the wound with fresh gauze.

Measuring with the “Clock Technique”

-

1Measure the wound dimensions using the linear measurement or ‘clock technique’. Get the longest length, width and depth of the wound with the body as an imaginary clock using a ruler measured in centimeters.[4]

- Keep in mind that the length may not be the longest measurement here. Sometimes, the width may be longer than the length depending on the clock position.

-

2Place the ruler on the widest portion of the width from 3 o’clock to 9 o’clock. This allows you to measure the width of the wound. When getting the length, remember that the heels are at 12 o’clock and toes at 6 o’clock. Place the ruler over the longest portion of the wound.

-

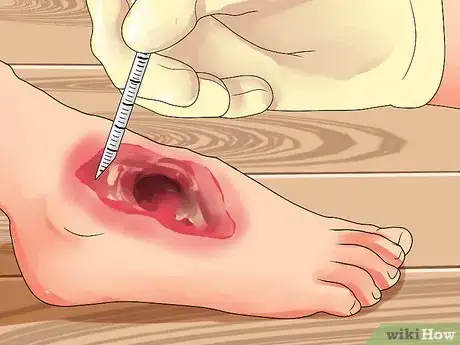

3Find the wound’s depth. Get the wound depth using a cotton pledget or applicator dipped in a normal saline solution to measure the deepest part of the wound bed.[5]

- Remove the applicator and hold it against the ruler to measure the depth of the wound margin based on the mark seen on the applicator stick.

- Then, estimate the amount of wound granulation in congruence to the percentage of the wound surface. Be sure to document your assessment findings properly.

Recognizing the Different Stages of a Healing Wound

-

1Learn the different phases of wound healing. It’s important to understand the physiologic process of wound healing in order to effectively manage and treat wounds properly.

-

2Recognize the inflammatory phase. The inflammatory phase is the body’s first line of defense against injury. It occurs when the blood vessels contract and release potent vasoconstrictors or chemical compounds that cause blood vessels to constrict in order to limit, if not to stop the bleeding.[6]

- At this point, the body sends white blood cells - particularly the neutrophils and macrophages - to the site of the wound to kill bacteria and promote wound healing.

- The inflammatory phase usually lasts around 2 to 4 days from the time of wound injury.

-

3Spot the proliferative phase. Overlapping with the inflammatory process, the proliferative phase begins around the third day, coinciding with the release of macrophages. The macrophages are responsible for attracting one of the most important cells, the fibroblasts, which initiate collagen and granulation tissue formation.[7]

- Healthy granulation tissue should not easily bleed and will appear pinkish or reddish in color. Dark granulation tissue indicates poor tissue perfusion or insufficient oxygen and nutrient levels. It may also indicate ischemia or infection.[8]

- Ischemia is characterized by a bluish discoloration around the wound which indicates poor tissue perfusion. It occurs when the blood flow to the capillaries or small vascular beds and blood vessels is impeded.

- Wound healing sets in when homeostasis between the collagen synthesis and breakdown is achieved.

-

4Identify the remodelling or maturation phase. The production of collagen continues even after wound healing. Collagen is a protein made of amino acids. It helps strengthen the structures of the body by acting like cement.

- During the maturation phase, remodeling or replacement of Type III collagen with Type I collagen takes place until such a time that the collagen tissue almost equates to the texture of normal skin and mimics approximately 80% of uninjured tissue.

References

- ↑ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1360405/

- ↑ http://www.rbcp.org.br/details/1500/pt-BR/pressure-ulcer-scale-for-healing-no-acompanhamento-da-cicatrizacao-em-pacientes-idosos-com-ulcera-de-perna

- ↑ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1360405/

- ↑ https://blog.wcei.net/top-wound-measurement-techniques

- ↑ https://blog.wcei.net/top-wound-measurement-techniques

- ↑ http://www.shieldhealthcare.com/community/popular/2015/12/18/how-wounds-heal-the-4-main-phases-of-wound-healing/

- ↑ http://www.shieldhealthcare.com/community/popular/2015/12/18/how-wounds-heal-the-4-main-phases-of-wound-healing/

- ↑ http://books.google.com/books?id=LaNuvQTjYeEC&pg=PA150&lpg=PA150&dq=how+to+measure+wound+granulation&source=bl&ots=xjIKexCtxX&sig=OPT5SdUv4TWC9dcT1WK5aid6IwI&hl=en&sa=X&ei=5gdAVLWeJsPeoASMzoKoCw&ved=0CEEQ6AEwBA#v=onepage&q=how%20to%20measure%20wound%20granulation&f=false

- Leaper DJ and Harding KG. (1998) Wounds: Biology and Management. Oxford University Press.

- 2 Hutchinson J (1992). The Wound Programme. Centre for Medical Education: Dundee.

- Cohen IK, Diegelmann RF, Lindblad WJ, eds. Wound Healing: Biochemical and Clinical Aspects. Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders; 1992.

- Cohen K, Diegelmann RF, Yager DR, et al. Wound Care and Wound Healing. In: *Schwartz SI, Shires GT, Spencer FC, Daly JM, Fischer JE, Galloway AC, eds. Principles of Surgery. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1999:263-96.

- Folkman J, Shing Y. Angiogenesis. J Biol Chem. Jun 5 1992;267(16):10931

- Baranoski S, Ayello EA. Wound Care Essentials: Practice Principles. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008:254–261.

About This Article

To measure wound granulation over time, start with a proper assessment of the wound, including how it as acquired, and where it’s located on the body. Next, use a ruler to measure the length and width of the wound in centimeters. Additionally, measure the depth by carefully inserting a saline-soaked cotton pledget in the wound, and measure that mark against a ruler. Wash hands with soap and keep covered with clean rubber gloves before dressing in gauze. To learn more about measuring wound granulation, like how understanding the different phases of healing can help you treat wounds properly, keep reading!

Medical Disclaimer

The content of this article is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, examination, diagnosis, or treatment. You should always contact your doctor or other qualified healthcare professional before starting, changing, or stopping any kind of health treatment.

Read More...