This article was co-authored by Michael Simpson, PhD. Dr. Michael Simpson (Mike) is a Registered Professional Biologist in British Columbia, Canada. He has over 20 years of experience in ecology research and professional practice in Britain and North America, with an emphasis on plants and biological diversity. Mike also specializes in science communication and providing education and technical support for ecology projects. Mike received a BSc with honors in Ecology and an MA in Society, Science, and Nature from The University of Lancaster in England as well as a Ph.D. from the University of Alberta. He has worked in British, North American, and South American ecosystems, and with First Nations communities, non-profits, government, academia, and industry.

There are 8 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page.

This article has been viewed 82,566 times.

If you live in the central-eastern part of the United States, you've probably seen walnut trees in parks or low-lying areas between rivers, creeks, and dense woods. The most common types of walnut trees in America are the black walnut, butternut (or white walnut), and English walnut. While they may look very similar, you can distinguish between them by looking for slight differences between the bark and leaves. Tasting the walnuts is also a fun (and delicious) way to figure out what kind of tree you’re looking at.

Steps

Examining the Fruit Casings and Trunk

-

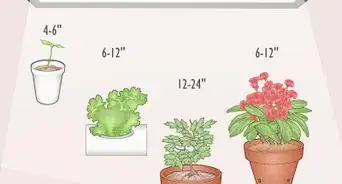

1Search for round or oblong green fruit growing on thin branches. Walnuts don't grow in a brown shell like we're used to seeing in stores. The brown shell is actually inside a larger muted lime-colored husk about the size of a small tennis ball. You'll typically see 2 or 3 green rounds growing near where the leaf-bearing twigs shoot off from thinner branches.[1]

- Keep in mind that black walnut trees don't grow walnuts until they're 4 to 7 years old. Butternuts take 2 to 3 years and English walnuts can take anywhere from 4 to 10 years. The most bountiful harvests usually occur after the tree (any variety) is 10 years old.

- The walnuts of English and black walnut trees are round while butternuts have oblong, papaya-shaped fruits.

- You may need to use binoculars since walnut trees can grow to be 50 to 100 feet (15 to 30 meters) tall and grow plumage high on their trunks.

-

2Distinguish between smooth, light bark or dark, ridged bark. The deep-gray bark of black walnut and English walnut trees has rounded ridges and deep furrows running vertically up and down the trunk. The bark of butternut trees is light gray and relatively smooth to the touch.[2]

- If you remove a little of the gray outer bark from the trunk of a black walnut or English walnut tree, you'll see a rich chocolate brown color underneath.

- The bark of black walnut trees can vary from dark brown to gray while butternuts have white-gray colored bark.

- This is a good way to identify walnut trees in the winter when they're not producing walnuts and their leaves have dropped.

Advertisement -

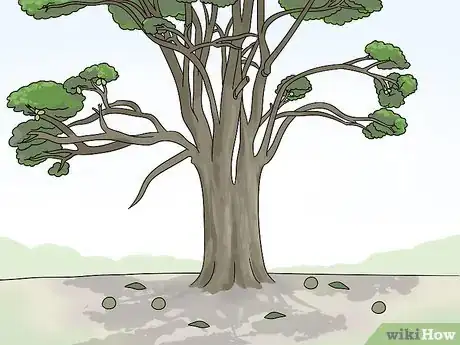

3Check the area around the tree for dying or yellowing plants. Black walnuts are allelopathic, which means they release chemicals into the ground that can poison plants up to 50 or 60 feet away. If the tree is standing alone without any neighboring trees or brush, there’s a good chance it’s a walnut tree.[3]

- Butternut and English walnut trees also release toxins but in much smaller quantities so that other nearby trees and shrubs can survive.

- However, there are some trees that can tolerate the black walnut's toxicity (note that this isn't an exhaustive list): Japanese maple, red maple, yellow birch, redbud, sycamore, oak (all varieties), black cherry, willow, and elm.

-

4Look for evidence of husks under the tree. Hungry squirrels, woodpeckers, and foxes love to visit these trees for a good meal and will often scatter shells and husk around the trunk. You may also notice small mounds of freshly piled dirt where gray squirrels may have buried the nuts.[4]

- Note that you're less likely to find cracked shell in the winter when the tree is dormant.

-

5Taste a walnut from the tree to see if it's mild, buttery, or earthy. English walnuts are known for their mild, pleasant flavor while black walnuts boast a strong, earthy taste. Walnuts from the butternut tree taste just like they sound—buttery![5]

- The shell of English walnuts is thinner and much easier to crack open than the other 2 varieties.

- The walnuts you're most likely to find in stores are typically from English walnut trees.

- Walnuts from black walnut trees are so strong they're typically used to make flavorings and extracts.

- Be mindful of breaking open the husk from a black walnut tree because it can stain your hands and clothing.

Warning: Only taste something if you're already relatively sure that you're dealing with a walnut tree. Otherwise, you might ingest something potentially harmful.

Inspecting the Leaves

-

1Observe the color of the leaves. During the spring and summer months, walnut leaves will be greenish-yellow. In the fall or winter, the leaves turn brown or bright yellow (not red or orange like other trees).[6]

- The leaves of walnut trees typically appear later in the spring than other trees and drop sooner during late summer or early fall.

- This applies to English, butternut, and black walnut trees.

-

2Look for stout twigs containing 5 to 25 serrated or smooth leaflets. The stout, rigid twigs each hold an odd number of leaflets (ranging from 5 to 25). The edges of each leaflet will appear toothed or serrated (like tiny etched zig-zags). However, the leaflets of English walnut trees are not toothed.[7]

- The largest leaflets can be found near the center of the twig.

- The leaflets will be slightly longer on butternut trees.

- English walnut trees have fewer leaflets than both butternut and black walnut trees (which have the most).

- The black walnut trees have compound leaves that occur alternately along the stems and are over a foot long, with around 23 leaves.

-

3Notice whether the leaflets are greatly staggered or not. Each leaflet shooting off of the rachis doesn’t sit directly across from another leaflets. Instead, the leaflets are arranged in an alternating fashion (staggering like stair steps). The leaflets of English walnuts are more spaced out, with about 0.7 inches (1.8 cm) to 1.9 inches (4.8 cm) between each leaflet.[8]

- Due to the way they gray, the leaves may have a feathered look to them.

-

4Look for a large or small terminal leaflet. Butternut walnut trees have a large end leaflet, sticking out in line with the twig. English walnut trees also have a large terminal leaflet, but with smooth (not serrated) edges. Black walnut leaves have a much smaller leaflet protruding from the tip of the twig.[9]

- Sometimes black walnuts won't grow terminal leaflets at all. Instead, they may have a small, fuzzy stub at the end of the rachis.

-

5Slice open a twig to see if the inside is chambered. Use a small knife to slice open a twig length-wise. If you see small chambers separated by fibrous, vertical walls (called "pith"), you know it's a walnut tree.[10]

- The twigs of every variety of walnut tree have chambered piths.

- English and black walnut trees will have dark brown pith while butternut trees are light tan inside the twigs.

-

6Crush a leaf in your hands and smell it if you're still not sure. Crunch up a leaf or two between your hands and take in the scent. If it's any kind of walnut tree (black, butternut, or English), it will smell like spiced citrus.[11]

- Some people say the smell is reminiscent of store-bought furniture polish.

- If your nose picks up a pungent odor, it’s a good sign that it is a black walnut tree, as their leaves have a distinct smell.

Warnings

- Be careful if you choose to break open the husk of a walnut from a black walnut tree because the inner shell carries a residue that can stain your hands, clothing, and even concrete.[12]⧼thumbs_response⧽

References

- ↑ https://extension.illinois.edu/blogs/extensions-greatest-hits/1999-10-02-preparing-black-walnuts-eating

- ↑ https://www.canr.msu.edu/news/wintertime_identification_of_black_walnut

- ↑ https://www.mortonarb.org/trees-plants/tree-and-plant-advice/horticulture-care/plants-tolerant-black-walnut-toxicity

- ↑ https://www.canr.msu.edu/news/wintertime_identification_of_black_walnut

- ↑ https://www.seriouseats.com/2011/04/what-are-english-walnuts-vs-black-walnuts-differences-nuts.html

- ↑ https://www.canr.msu.edu/news/walnut_anthracnose_is_putting_an_early_end_to_many_leaves

- ↑ https://www.depauw.edu/files/resources/trees_at_the_Nature_Park.pdf

- ↑ https://www.depauw.edu/files/resources/trees_at_the_Nature_Park.pdf

- ↑ https://www.canr.msu.edu/news/wintertime_identification_of_black_walnut