This article was co-authored by Clinton M. Sandvick, JD, PhD. Clinton M. Sandvick worked as a civil litigator in California for over 7 years. He received his JD from the University of Wisconsin-Madison in 1998 and his PhD in American History from the University of Oregon in 2013.

There are 22 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page.

This article has been viewed 222,522 times.

Copyright protects original works of authorship, such as books, movies and songs. In general, works that have been copyrighted cannot be used without the permission of the author. Every country has its own copyright laws, which means that even if a work is not protected by copyright in the U.S., it may be protected by copyright in a foreign country. To find out whether a work is copyrighted in the U.S., first examine the work itself for clues as to whether or not it is protected by copyright. Works not protected by copyright are considered to be in the "public domain" and can be used freely. If you suspect a work may be protected by copyright, search for it through the records of the U.S. Copyright Office. Finally, even if a work is copyrighted, consider using it on a limited basis within the parameters of "fair use" or other statutory exemption, or within the terms of a specific license or an implied license.

Steps

Looking For Clues on the Work Itself

-

1Examine the work for a copyright notice. Many works state whether or not they have been copyrighted, although it is no longer legally required, even in the USA.[1] You will know that the work has been copyrighted if it includes a "copyright notice," which is marked either by a "c" in a circle (©) or the word "copyright" followed by the date of first publication and the name of the copyright owner. [2]

- If the work is a book, look for a copyright page. It is typically found on the back side of the title page. On older works it may be on the title page or on the last page of the book.

- If the work is a film or a television show, the copyright is usually included at the end of the credits. If you have a physical copy of a DVD or tape, the label or package may have a copyright notice.

- If the work is a cassette, CD or LP, look for a reference to the copyright on the label or packaging. It may include a "circle-P" mark for "phonograph copyright".

- If the work is a magazine, the copyright will likely be found near the Table of Contents at the beginning of an issue.

- If the work is a digital photograph, the copyright will be indicated by a tag. If it is a print photograph, the copyright will be on the back of the image.

-

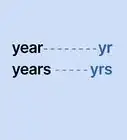

2Look at the date. All copyrights have a statutory duration. Some works have entered the public domain because the copyright on them has expired. This applies to:

- All works published in the U.S. before 1923

- Some works published with a copyright notice after 1922 if, for example, the copyright was published before 1964, but never renewed. To find out whether a copyright was renewed, you will likely have to search the records of the U.S. Copyright Office. Published works were required to carry a "copyright notice" only until 1989.[3]

- Works made for hire that were published more than 95 years ago

- All works published more than 95 years ago, beginning in 2019.

- Unpublished works for which the author is known and the author died more than 70 years ago, or 120 years from its date of creation, whichever expires first.[4]

- Phonographs (sound recordings) created or published in the US prior to 1972 currently have no statutory copyright protection under US federal law, but certain exclusive rights may be covered by relevant state laws, at least until preempted in 2067. It is quite possible that even sound recordings more than 120 years old may still have copyright protection under state laws.[5]

- In 2018 the US Congress passed a new law granting specific, retro-active, copyright protections to pre-1972 sound recordings published in the USA: either 95, 96, 100 or 110 years, depending upon its publication date. [6] For example, sound recordings published prior to 1923 now have copyrighted performance rights until 2021; those published after 1956 have 95-year copyright protection, during the "transition period" ending in 2067.

Advertisement -

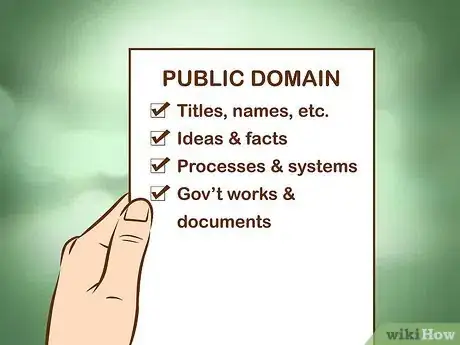

3Consider the type of work. Some works automatically enter the public domain upon creation because they are not copyrightable. These include:

- Titles, names, short phrases and slogans, familiar symbols, numbers

- Ideas, concepts and facts (e.g., the date of the Gettysburg Address)

- Processes, methods of operations, and systems

- Works and documents created by the US government. Note that the US government also publishes works created by others, for which there may be a valid and enforceable copyright.

-

4Look for the "CC0" Public Domain mark. Some owners of copyrighted works choose to waive their interests and place their works in the public domain through the website "Creative Commons." You can identify a work that has been dedicated to the public domain through the "CC0" mark.[7]

- When searching for images online, look for small print under the image that reads: "Copyright and related rights waived via CC0."[8]

- Authors are also allowed to simply "disclaim" their right to enforce their own copyright, but it must be done in writing and in a way to make it unambiguously irrevocable, without regard to the "Creative Commons" procedures.

-

5Determine whether a work is unpublished. Unpublished material may be protected by copyright law, even if it contains no reference to a copyright and has not been registered with the Copyright Office, provided it has not expired.[9] The law only requires that such works be fixed in a tangible form. For this reason, you need to be even more careful about using material that has never been published.[10]

- To be clear, any copy you have found qualifies as being "in tangible form", even if it is in computer memory or encoded in a form that you cannot read or understand.

- To determine whether or not a work has been published, find out whether or not it was intended for public distribution. If only a few copies were created and distribution was limited, it is likely unpublished.

- If you believe a work is unpublished, find out whether the author is deceased. Copyright in an unpublished work will expire 70 years after the death of the last surviving author. If an author is anonymous, or the date of the author's death is unknown, or it was a work made for hire, the copyright will expire 120 years after the date on which the work was created.

- Avoid using unpublished material found in archives or manuscript collections unless you are certain the copyright has expired. Much of this material is likely still protected by copyright.

- As mentioned above, Congress changed the copyright law in 2018 to grant 95-year protection to pre-1972 sound recordings. Unpublished pre-1972 sound recordings now have federal copyright protection for 95 years from "date of fixation", subject to many of the same exceptions and limitations of other copyrights. [11]

-

6Be wary of "orphan works." Many works published (with copyright notice) after 1922 are presumably still protected by copyright, but their owners cannot be found. Such works are referred to as "orphan works." You should be wary of using material from orphan works, as the true owner may eventually come forward and accuse you of violating his copyright.[12]

- Mass digitalization projects, like Google Books, are replete with untraceable photos, letters and text that are technically still protected by copyright, even though their owners cannot be found. Until Congress passes legislation authorizing the use of such works, you run the risk of violating copyright law in taking material from them.

-

7Refer to websites that store only public domain works. Some websites collect books, images, illustrations, audio, and films where the copyright term has expired or the creator has not renewed the license. These works are in the public domain and free to be used for any purpose. Such websites include:

- Smithsonian Institution Public Domain Images

- New York Times Public Domain Archives

- Project Gutenberg, a collection of public domain electronic books

- Librivox, public domain audio books

- Prelinger Archives; a vast collection of advertising, educational, industrial, and amateur films.

Searching the Copyright Database

-

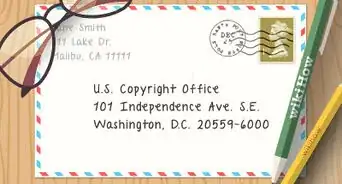

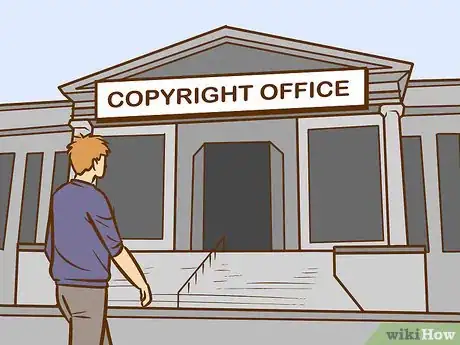

1Conduct your own search at the Copyright Office. Identify the author, title and publisher of a work and then visit the U.S. Copyright Office to search for records regarding your work.

- For works registered or renewed after 1977, the Copyright Office offers an online, web-base database search in the Copyright Catalog.

- The Copyright Office is located in the Library of Congress in Washington D.C. and is open to the public on Monday through Friday from 8:30 a.m. to 5:00 p.m.[13]

- Register with the Public Information Office, which is located at LM-401 on the fourth floor of the James Madison Memorial Building.[14]

- Once you are a registered user, visit the Copyright Office Public Records Reading Room (also on the fourth floor of the James Madison Memorial Building.[15]

- Your search method will depend on the date in which the work was copyrighted. This presents a challenge since presumably you won't know whether the work was copyrighted in the first place. Based on what you do know about the work, make a guess as to whether it would have been copyrighted before or after 1978. For works copyrighted before January 1, 1978, use the physical card catalogue to search for your work. For works copyrighted after January 1, 1978, use the online card catalogue. If you believe it could have either, search both catalogues.[16]

- If using the physical card catalogue, ask the Copyright Office employee on duty for help searching your work and retrieving the certificate registration and any other ownership documents.[17]

- If using the online card catalogue, approach one of the available computers and click on "Search Records" from the home screen. On the next screen, click on "Search the Catalogue."[18]

- Insert a search term into the top box. Indicate the type of search term (i.e. title of the work, the name of the author or keyword) in the bottom box. If searching by title, omit the initial article (i.e. "The" or "A"). Click "Begin Search" to perform the search.[19]

- The search will produce a list of titles on the next screen. Look for the title and date that matches your work. Click on the correct work to view the certificate of registration and other records related to the work.[20]

-

2Examine the certificate of registration. If you are performing the search on your own through the Copyright Office, you will need to examine the certificate of registration to determine who initially acquired ownership. You will also need to review other transfer and renewal documents to find out if ownership was transferred to a third party.[21]

- When reviewing the certificate of registration, look for the owner's name in the space in Section 4 entitled “Copyright Claimant.”[22]

- Look for assignments and other transfer documents to find out whether ownership was transferred to another party.[23]

- Examine the date of the work's copyright notice. Any work published before 1923 is in the public domain.[24]

- Look for renewal notices. Any works registered or published before 1964 in which a copyright was not renewed are now in the public domain. Any works registered or published after 1963 may still be protected even if the copyright was not renewed.[25]

-

3Hire the Copyright Office to perform search on your behalf. If you are not able to or do not feel comfortable searching the records of the Copyright Office on your own, you can hire the Copyright Office staff to perform the search and send you a written report. This search will cost you $200 for each hour of research and there is a two hour minimum. [26]

- Fill out the online request form on the Copyright Office website: www.copyright.gov/forms/search_estimate.html.

- The Copyright Office will respond with an estimate of the total search fee within two to five days.[27]

- Provide whatever detailed information you know about your request, such as the title of the work, names of authors, name of the probable copyright owner, the approximate year when the work was published and the type of work involved (book, play, musical composition, sound recording, photograph, etc.).[28]

-

4Hire a private search company. As an alternative to hiring the Copyright Office staff to conduct your search, you can hire a private company to search Copyright Office records for you.[29]

- There are two advantages to hiring a private company to conduct your search. First, a private company can deliver reliable results more quickly than the Copyright Office staff, within two to ten days of your request. Second, in addition to determining whether a work is in the public domain or whether you can obtain the rights to use the work, a private company can provide other services, such as tracing the copyright history of a fictional character or locating similarly titled works.

- Private search companies charge from $75 to $300 per search.

- The largest and best known copyright search company is Thomson & Thomson Copyright Research Group (www.thomson-thomson.com).

Limiting Yourself to “Fair Use” of the Copyright

-

1Create something new rather than copying. In determining whether the use of copyrighted material is considered "fair," courts consider the purpose and character of the use. If the material is used in a way that is transformative, meaning that it alters the fundamental character of the original work, the use is considered fair. However, if the new version merely copies or supersedes the original work, then the use is not fair. [30]

- For example, a poet who uses a line from a T.S. Eliot poem in her own poem is likely within the doctrine of "fair use" because she is using it to create a new poem.

-

2Use only for certain purposes. The purpose for which you use the copyrighted work is also critical. Generally, the following uses are deemed "fair use" of copyrighted material:[31]

- Criticism and comment-- for example, while copying a song lyric is generally not permitted, it may be considered "fair use" if reproduced within the context of a music review.[32]

- News reporting

- Research and scholarship

- Non-profit educational use-- for example, photocopying of limited portions of written works by teachers for classroom use.[33]

- Parody

-

3Consider the nature of the copyrighted work. Another factor courts consider is the nature of the copyrighted work. Certain types of works, like unpublished or highly creative works, are protected more closely. Therefore, your use of such works is more likely to violate copyright law.[34]

- Determine whether the work you want to use is published or unpublished. If only a few copies were made and it was never intended for public distribution, it is likely unpublished and any use of it could be risky.

- Ask yourself if the work is highly creative or purely factual. If you choose to take material from a work that is highly creative, like a poem or a song, you are more likely to violate copyright law.

-

4Restrict your use to a small and relatively insignificant portion of the copyrighted work. Courts also consider the amount of the copyrighted work that was used and the relative importance of that section to the work as a whole.[35]

-

5Evaluate how your use will affect the value of the original work. A final factor courts consider is the impact of your use on the existing and potential market value of the original work.[38]

- Ask yourself: will your use of the copyrighted work deprive the owner of the copyright of a significant source of potential or existing income?

- For example, a sculptor used copyrighted photographs to create sculptures and sold them for several hundred thousand dollars. Even though the sculptor used the photographs in a way that was entirely new, a court found the sculptor had violated copyright law by depriving the photographer of a potential market that existed for his photographs.[39]

References

- ↑ https://www.copyright.gov/title17/92chap3.html#302

- ↑ http://fairuse.stanford.edu/overview/copyright-research/getting-started/#sthash.52F7fwn9.dpuf

- ↑ https://www.copyright.gov/title17/92chap4.html#401

- ↑ https://www.copyright.gov/title17/92chap3.html#302

- ↑ https://www.soundexchange.com/advocacy/pre-1972-copyright/

- ↑ https://www.copyright.gov/music-modernization/pre1972-soundrecordings/

- ↑ https://creativecommons.org/about/cc0

- ↑ https://wiki.creativecommons.org/Marking_your_work_with_a_CC_license#Adding_a_CC0_public_domain_notice_to_your_work

- ↑ https://www.copyright.gov/title17/92chap3.html#302

- ↑ http://www2.archivists.org/publications/brochures/copyright-and-unpublished-material

- ↑ https://www.copyright.gov/music-modernization/pre1972-soundrecordings/

- ↑ http://fairuse.stanford.edu/2014/03/12/deadline-april-14th-public-invited-weigh-orphan-works-us-copyright-office/

- ↑ http://www.copyright.gov/help/hours_location.html

- ↑ http://www.copyright.gov/help/hours_location.html

- ↑ http://www.copyright.gov/help/hours_location.html

- ↑ http://www.copyright.gov/records/

- ↑ http://www.copyright.gov/circs/circ23.pdf

- ↑ http://www.copyright.gov/records/voyager_tutorial.pdf

- ↑ http://www.copyright.gov/records/voyager_tutorial.pdf

- ↑ http://www.copyright.gov/records/voyager_tutorial.pdf

- ↑ http://fairuse.stanford.edu/overview/copyright-research/searching-records/

- ↑ http://fairuse.stanford.edu/overview/copyright-research/searching-records/

- ↑ http://fairuse.stanford.edu/overview/copyright-research/searching-records/

- ↑ http://fairuse.stanford.edu/overview/copyright-research/searching-records/

- ↑ http://fairuse.stanford.edu/overview/copyright-research/searching-records/

- ↑ http://copyright.gov/help/faq/faq-services.html#whoowns

- ↑ www.copyright.gov/forms/search_estimate.html

- ↑ http://copyright.gov/circs/circ22.pdf

- ↑ http://fairuse.stanford.edu/overview/copyright-research/searching-records/

- ↑ http://www2.archivists.org/publications/brochures/copyright-and-unpublished-material

- ↑ http://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/fair-use-rule-copyright-material-30100.html

- ↑ http://fairuse.stanford.edu/overview/introduction/getting-permission/

- ↑ http://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/fair-use-rule-copyright-material-30100.html

- ↑ http://www2.archivists.org/publications/brochures/copyright-and-unpublished-material

- ↑ http://www2.archivists.org/publications/brochures/copyright-and-unpublished-material

- ↑ https://www.rocketlawyer.com/article/difference-between-public-domain-and-fair-use-ps.rl

- ↑ https://www.rocketlawyer.com/article/difference-between-public-domain-and-fair-use-ps.rl

- ↑ http://www2.archivists.org/publications/brochures/copyright-and-unpublished-material

- ↑ http://fairuse.stanford.edu/overview/fair-use/four-factors/

- ↑ https://www.copyright.gov/music-modernization/pre1972-soundrecordings/

- ↑ https://www.copyright.gov/title17/92chap1.html

About This Article

To find out if something is copyrighted, start by checking it for a copyright mark, which may be a “C” in a circle, or the word “copyright” followed by a date and the name of the copyright owner. Additionally, look at the date, since the copyrights on all works published in the U.S. before 1923 have expired. If you can’t tell by examining the work, you can try searching the records of the U.S. Copyright Office. Check the online database for works registered or renewed after 1977, or visit the office in person to check on older works. For more tips from our Legal co-author, like how to figure out what types of works can be copyrighted, scroll down!

-Step-13.webp)