X

This article was co-authored by Clinton M. Sandvick, JD, PhD. Clinton M. Sandvick worked as a civil litigator in California for over 7 years. He received his JD from the University of Wisconsin-Madison in 1998 and his PhD in American History from the University of Oregon in 2013.

There are 14 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page.

This article has been viewed 35,259 times.

The administration of someone's estate is done by administrators or executors. When a person dies, their estate must be inventoried, managed, and closed.[1] If you are appointed an executor or administrator, you will need to learn about your role, including what you can and cannot do with the estate.

Steps

Part 1

Part 1 of 6:

Getting Appointed Executor or Administrator

-

1See if you are eligible. An executor is a person named in the decedent's will to administer the estate. An administrator is a person eligible to administer an estate when the decedent leaves no will (dies intestate) or when the executor will not or cannot serve.

- Most states allow any person who is over the age of 18 to administer an estate.

- Some states may require you to be a citizen of the state where the estate is being probated.

- Most states do not allow felons to act as administrators or executors.

- In California, certain individuals have priority for being named an administrator.[2] For example, relatives of the decedent, in a specific order, have priority over non-relatives.[3]

-

2Request appointment. If you are eligible, meaning you have been named in the decedent's will or you meet the administrator eligibility requirements in your state, you can petition the court to allow you to administer the estate. Contact the probate court in the county where the estate will be administered and request the form necessary for appointment.[4]

- Forms may vary depending on whether you are requesting to be an administrator or executor. Make sure you get ahold of the correct one.

- Forms will usually be posted online with your local court website.[5]

- Each state's forms will vary, so be sure you are filling out the correct one.

Advertisement -

3Complete the form. Once you obtain the correct form, you will need to fill it out accurately and completely. In general, you will need the following information:

- The decedent's name;

- Statements ensuring you meet the eligibility requirements; and

- The names of other possible administrator candidates, so you can provide them with adequate notice.

-

4File your application. After completing the form and making the required number of copies (usually two), file your application with the clerk of courts in the county where the estate will be administered. There is usually a filing fee required. If you cannot afford the filing fee, you may be able to waive it if you can convince the court of your financial hardship. Call ahead of time to ask about the fee amount; each state will be different.

-

5Notify beneficiaries. When you apply to be the administrator of an estate, you will have to inform all beneficiaries of your application.[6] You can find the beneficiaries by looking at the will.[7] If the decedent does not have a will, state law will determine who must be informed.[8]

- When you notify a beneficiary, you will complete a notice form, which is usually available on state court websites. Once you complete the notice form, you will send it to all of the beneficiaries you can find.

-

6Attend the appointment hearing. The court will schedule a hearing to give interested parties a chance to object to the appointment. Usually, the hearing is a formality and no one objects to the administrator's appointment.

- If someone challenges your appointment, then the court will listen. At the hearing, each side will argue why they should be appointed administrator.

- In some states, the hearing can also be dispensed with if all interested parties sign waivers.[9]

-

7Get approved. Once the court approves you as the administrator, you will get “Letters of Administration” or "Letters Testamentary."[10] These letters allow you to act on behalf of the estate.

- For example, you may need to show one of these letters to a bank in order to close the decedent's account and get the remaining balance.

Advertisement

Part 2

Part 2 of 6:

Understanding Your Role as an Executor or Administrator

-

1Learn about your duties. Generally, an administrator or executor preserves the deceased's estate in order to pay off debts and taxes before distributing the remainder to the people entitled to it.[11] The full set of duties are extensive. A partial listing includes:

- Filing the will in the probate court;

- Determining whether the will needs to be probated;

- Finding the deceased person's assets and keeping them safe;

- Contacting agencies and businesses;

- Finding creditors the deceased owed money to and paying off legitimate claims;

- Contacting anyone in debt to the deceased and collecting on the debts;

- Paying taxes;

- Distributing property specifically given to beneficiaries or heirs;

- Liquidating the remainder of the estate; and

- Closing the estate.

-

2Understand potential liability. As an executor or administrator, you have a duty to exercise reasonable care when dealing with the estate's property. You also owe the beneficiaries a duty of loyalty and good faith.[12] [13] If you breach either of these duties, then the beneficiaries could sue you in court.[14]

- You will discharge your duty of reasonable care if you use the same amount of care when handling the estate's property as you would use when handling your own.[15] You discharge your duty of loyalty when you administer the estate solely in the beneficiary's interest and not in your own.[16]

- State law may impose additional fiduciary duties, which can often be quite specific. For example, California requires that executors disclose assets, properly complete accounting, and distribute assets properly. Virginia requires that executors deal with multiple beneficiaries impartially and that the executor and defend against lawsuits.[17]

- For a full list of fiduciary duties, you should contact a lawyer.

-

3Know how you will be compensated. You typically can be compensated for the work that you perform as the executor or administrator. Compensation levels vary by state. States often peg the amount of compensation to the size of the estate. For example, executors in Oregon are entitled to compensation according to the following formula:

- 7% of the first $1,000 of the estate

- an additional 4% of any amount over $1,000 but less than $10,000

- an additional 3% of any amount above $10,000 up to $50,000

- an additional 2% of any amount over $50,000.

- As executor in Oregon, you would also be entitled to 1% of non-probate property, e.g., life insurance proceeds.[18]

-

4Weigh the pros and cons. Before taking on the responsibility of becoming an executor or administrator, you should take some time to consider whether or not you want to do the job. A good executor or administrator is careful, patient, organized, and focused on doing an excellent job.[19] Realize that even if you are named as the executor in a will, you can always decline.[20] Furthermore, you can stop being an executor or administrator at any time if you feel it is necessary. You should also consider:

- The amount of time you have to commit;

- How familiar you are with the estate;

- How well you get along with the beneficiaries; and

- Whether or not there is anyone else who can do the job or help serve as co-executor.

-

5Meet with an attorney. While you do not need an attorney to be an executor or administrator, you should consider consulting one if issues arise that you are not comfortable handling on your own.

- In some states, for example New Hampshire, if you consult a lawyer for a proper purpose, the attorneys' fees will be payable out of the estate.

Advertisement

Part 3

Part 3 of 6:

Deciding How You Will Administer the Estate

-

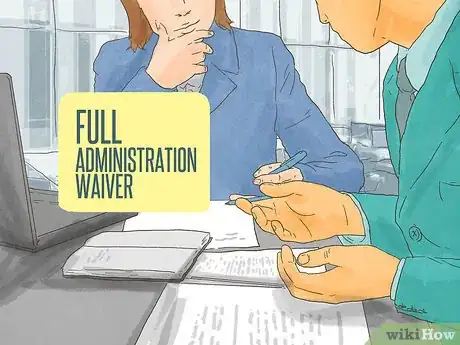

1Know whether you can file a waiver of full administration. In circumstances where the decedent's entire estate is passed down to a single individual, you can administer the estate simply by filing a waiver of full administration, which certifies that no outstanding debt exists.

- You must file the waiver within a specific time period, usually between six months to one year of your appointment.

- If you qualify for this type of waiver, you will not need to take an inventory of assets and you will not need to complete an accounting.

- However, any interested individual can petition the court for a full administration up until you file the waiver.

-

2Determine if you are eligible for voluntary administration. If you are administering a small estate with no real estate holdings, you can apply for a voluntary administration. This process is a simplified version of the regular process.

- In New Hampshire, you can file for this process if the decedent's estate involves only personal property with a total value of $10,000 or less.

-

3Administer the estate through the regular process. If the estate is not eligible for a waiver or voluntary administration, you will have to administer the estate through the regular process.

Advertisement

Part 4

Part 4 of 6:

Inventorying the Estate

-

1Find the will. If you are named the executor in the decedent's will, you will be required to find and file the decedent's will within a certain time period after their death. In New Hampshire, you are required to file the will within 30 days of the decedent's death. If you are appointed administrator, you will have to file the will after your appointment.

- Filing the decedent's will starts the estate administration process.

- If the decedent dies without a will, they are determined to have died intestate, and your state's intestacy statute will determine how the estate will be administered.

-

2Collect the property. As the administrator, it is one of your duties to determine and protect the estate's assets. To collect property, you will have to use your power as administrator or executor to take control of property and ensure its safekeeping.

- For example, you may have to collect money from the decedent's bank account. To do so, go to the bank and show them your letters of administration. At this point, the bank should honor our authority, close the accounts, and provide you with the money that was in them.

- In another example, if you are trying to collect something like a vehicle (or another piece of tangible personal property), you may have to locate that property and keep t in a safe place until it is sold or distributed.

-

3Inventory the property. Once you have collected the property, you will be required to inventory that property. In order to show the court you have successfully completed this task, you will be required to file an inventory form. The inventory form will contain an itemization of all property, its value, and a description.

- In New Hampshire, the inventory form can be found online and must be filed within 90 days after your appointment as executor or administrator.

Advertisement

Part 5

Part 5 of 6:

Managing the Estate

-

1Allow creditors to make claims. An estate must remain open for at least six months from the date of your appointment to allow creditors the opportunity to make claims against the estate. When it comes time to pay the decedent's debts with the assets of the estate, you will have to pay them in order of priority. If there is not enough cash in the estate to pay the debts, you will have to sell property in order to make the payments.

- In New Hampshire, the order of priority is:

- Administrative expenses of the estate;

- Reasonable funeral and burial expenses;

- Debts and taxes with preference under federal law; and

- All other debts.

- In New Hampshire, the order of priority is:

-

2Collect debts. Part of managing the estate means collecting outstanding debts owed to the decedent. You need to inform those who owed the decedent money that they should make payment to the estate. Be sure to send debtors a letter to this effect, and keep copies on file.[21] Also, consider checking with an attorney to find out how long debtors have to pay the debts they owe the estate. Be sure to include this information in the letter you send.

-

3File taxes. As the administrator or executor, you are required to file all the necessary federal and state tax returns on behalf of the decedent and the estate. You can do this by obtaining a federal tax identification number for the estate and filing the proper tax forms.

- All taxes must be filed within nine months of the decedent's death, unless you receive an extension.

Advertisement

Part 6

Part 6 of 6:

Closing the Estate

-

1Make the final distribution of assets. Once all debts have been paid and all the property has been collected, you will distribute the remaining property to all the decedent's beneficiaries. If there is a will, you will distribute the assets in conformance with the wishes contained within it. If the decedent died intestate, you will distribute the remaining assets in conformance with your state's intestacy statute.

- You will need to fill out receipts reflecting all of these distributions and they must be signed by the recipients. These receipts must be filed with the court.

-

2Prepare a final accounting. Once the estate has been managed to completion, you will need to file a final accounting with the court. A final account is a detailed list of assets received, debts paid, and distributions made. When you submit the account to the court, it must be in balance.

- There is usually a filing fee required. In North Carolina, the fee is $0.40 per $100 on the money and assets received into the estate, with a $15 minimum.

-

3Close the estate. At this point, if the court is satisfied, the estate will be closed and the court will instruct you that your duties as an administrator or executor have been fulfilled.

Advertisement

References

- ↑ http://estate.findlaw.com/estate-administration/estate-administration.html

- ↑ http://www.alameda.courts.ca.gov/Pages.aspx/Preparing-the-Petition

- ↑ http://www.alameda.courts.ca.gov/Pages.aspx/Preparing-the-Petition

- ↑ http://www.superiorcourt.maricopa.gov/sscDocs/packets/pbip1iz.pdf

- ↑ http://www.courts.ca.gov/forms.htm?filter=DE

- ↑ http://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/executor-estate-checklist-29458.html

- ↑ http://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/executor-estate-checklist-29458.html

- ↑ http://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/executor-estate-checklist-29458.html

- ↑ http://www.czepigalaw.com/the-probate-process.html

- ↑ https://www.nolo.com/dictionary/letters-of-administration-term.html

- ↑ http://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/what-does-executor-do-30236.html

- ↑ http://www.wolcottriversgates.com/fiduciary-duties-during-administration-of-trusts-and-estates/

- ↑ http://executor.org/plan/role-and-responsibilities/duties-of-an-executor/

- ↑ http://info.legalzoom.com/failure-execute-fiduciary-responsibilities-executor-will-4722.html

- ↑ http://info.legalzoom.com/failure-execute-fiduciary-responsibilities-executor-will-4722.html

- ↑ http://info.legalzoom.com/failure-execute-fiduciary-responsibilities-executor-will-4722.html

- ↑ http://www.wolcottriversgates.com/fiduciary-duties-during-administration-of-trusts-and-estates/

- ↑ http://www.hg.org/article.asp?id=22092

- ↑ http://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/accept-job-as-executor-estate-32439.html

- ↑ http://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/accept-job-as-executor-estate-32439.html

- ↑ http://executor.org/plan/notify-organizations-of-death/send-notice-of-death-to-debtors/

About This Article

Advertisement