Firefox dev tools show that https://www.google.com is using a certificate signed with SHA-1. Why is Google doing this when they are phasing out the certificate themselves?

Shouldn't this only hurt Google's reputation and interests?

Firefox dev tools show that https://www.google.com is using a certificate signed with SHA-1. Why is Google doing this when they are phasing out the certificate themselves?

Shouldn't this only hurt Google's reputation and interests?

This may be a case of "do what I say, not what I do". Note that Chrome complains about use of SHA-1 for signing certificates whose validity extends beyond the end of year 2015. In this case, Google's certificate is short-lived (right now, the certificate they use was issued on June 3rd, 2015, and will expire on August 31st, 2015) and thus evades Chrome's vengeful anathema on SHA-1.

Using short-lived certificates is a good idea, because it allows for a lot of flexibility. For instance, Google can get away with using SHA-1 (despite Chrome's rigorous stance) because the algorithms used to guarantee the integrity of a certificate do not need to be robust beyond the certificate expiration; thus, they can use SHA-1 for certificates that live for three months as long as they believe that they will get at least a three-month prior notice when browsers decide that SHA-1 is definitely and definitively a tool of the Demon, to be shot on sight.

My guess as to why they still use SHA-1 is that they want to interoperate with some existing systems and browsers that do not support SHA-256 yet. Apart from pre-SP3 Windows XP systems (that should be taken off the Internet ASAP), one may expect that there still linger a number of existing firewalls and other intrusion detection systems that have trouble with SHA-256. By using a SHA-256-powered certificate, Google would incur the risk of making their site "broken" for some customers -- not by Google's fault, but customers are not always fair in their imprecations.

So Google's strategy would appear to be the following:

It is a pretty smart (and somewhat evil) strategy, if they can pull it off (and, Google being Google, I believe they can).

Meta-answer/comment.

Re. Thomas' answer:

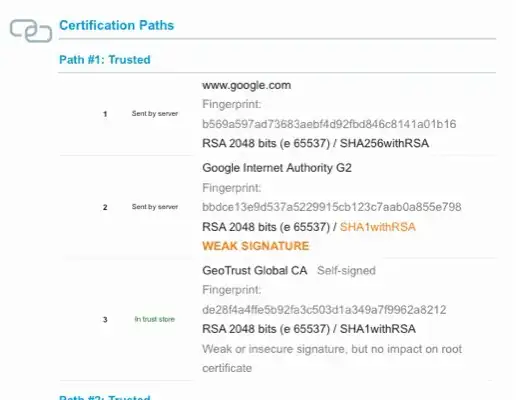

I just ran an SSL Labs scan on a Google.com server and it seems that the end entity cert is in fact SHA256withRSA. But the (single) intermediate is only SHA1withRSA. No idea why.

Screenshot:

As noted by StackzOfZtuff, the SHA1-signature is in the long-lived¹ intermediate CA «Google Internet Authority G2».

This key pair is stored in a FIPS 140-2 Level 3 certified Hardware Security Module, where it was generated.² The HSM itself is able to sign using SHA1, SHA-256, SHA-384 or SHA-512.³

However, the signature for the HSM certificate was done by GeoTrust -presumably in April 2013-, using their GeoTrust Global CA root, when it was common to use SHA-1 signatures. It would be possible to replace that signature with a SHA256 one by cross-signing by the SHA256 root and replacing the certificate sent by the server, but it hasn't been done.

Note that if an attacker was able to create a SHA-1 key colliding with Google Internet Authority, the old signature would still work,⁴ so the Intermediate CA key whould have to be revocated, and thus there may be little interest on that cross-signing path, waiting instead for the HSM replacement, which I guess is programmed to be performed within next 12 months.

¹ 05/04/2013 15:15:55 to 31/12/2016 23:59:59 GMT

² https://pki.google.com/GIAG2-CPS-1.2.pdf section 6.1.1

³ Per appendix B

⁴ Although all SHA-1 signing roots should be revoked when that becomes feasible…