Immigration Reforms in the 1960s

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 (also known as the Hart-Celler Act) changed the nation's laws regulating immigration. The act had a profound and long-term affect on immigration into the United States and, thus, on American demographics. The act was co-sponsered by Representative Emanuel Celler of New York and Senator Philip Hart of Michigan, and it was strongly supported by United States Senator Ted Kennedy of Massachusetts.

Focus on Skill and Family

The Act abolished the National Origins Formula, which had been in place since the Immigration Act of 1924. The National Origins Formula had set immigration quotas for specific countries, effectively giving preference to Northern and Western Europe over Eastern Europe, Asia, South America, and Africa. This national origins quota system was viewed as an embarrassment by, among others, President John F. Kennedy, who called it "nearly intolerable"; many argued that such an unequal policy hampered American attempts to compete ideologically with the Soviet Union.

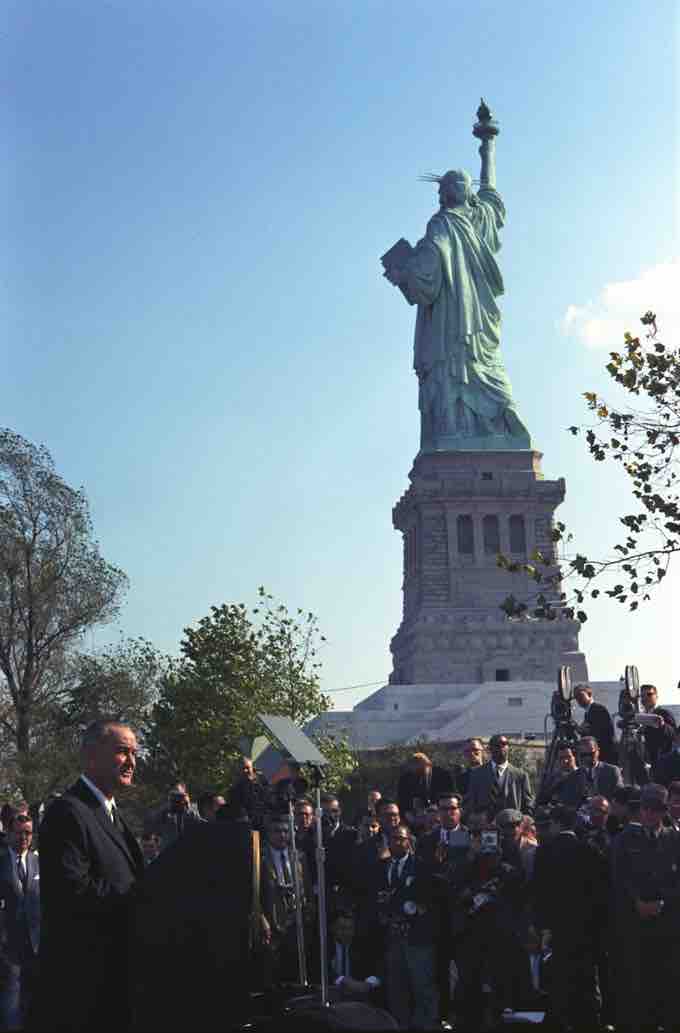

The National Origins Formula was replaced with a preference system based on immigrants' skills and family relationships with U.S. citizens or residents. Numerical restrictions on visas were set at 170,000 per year and per country-of-origin, not including immediate relatives of U.S. citizens or "special immigrants" (including those born in "independent" nations in the Western Hemisphere; former citizens; ministers; and employees of the U.S. government abroad). President Lyndon Johnson signed the bill at the foot of the Statue of Liberty as a symbolic gesture.

The Act's Passage

Despite controversy amidst the public, the House of Representatives voted 326 to 70 (82.5%) in favor of the act, while the Senate passed the bill by a vote of 76 to 18. The act had bi-partisan support in the senate, with 52 of 67 Democrats and 24 of 28 Republicans voting "yes." Most of the "no" votes were from the southern belt, which was then strongly Democratic. On October 3, 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the legislation into law, saying "This [old] system violates the basic principle of American democracy, the principle that values and rewards each man on the basis of his merit as a man. It has been un-American in the highest sense, because it has been untrue to the faith that brought thousands to these shores even before we were a country."

Public Response

The majority of the American people were opposed to the Immigration and Nationality Act, largely due to xenophobia and fears of how immigrants from these nations could influence the dominant white culture of the United States. To convince people of the legislation's merits, the act's proponents asserted that the act would not significantly influence American culture. President Johnson minimized the act's significance, calling it "not revolutionary." Secretary of State Dean Rusk estimated that only a few thousand Indian immigrants would enter the country over the next five years, and other politicians, including Edward Kennedy, hastened to reassure the public that the demographic mix would not be affected. In fact, these assertions would prove highly inaccurate.

Effects of the Act

The Immigration and Nationality Act did change American demographics, leading to increases in immigration from Mediterranean Europe, Latin America, and Asia. By the 1990s, America's population growth was more than one-third driven by legal immigration, as opposed to one-tenth before the act. Ethnic and racial minorities, as defined by the census bureau, rose from 25% in 1990 to 30% in 2000. Per the 2000 census, roughly 11.1% of Americans were foreign-born, a major increase from the low of 4.7% in 1970. One-third of those that were foreign-born were from Latin America, while one-fourth came from Asia.

Immigration has always been a widely debated issue in the United States since the country's inception by European settler-invaders in the 18th century. The new waves of immigration enabled by the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 heightened this controversy among the American public. Despite economic fears held by many, immigrants have made significant contributions to the overall economy in the United States. However, debate continues to wage between ideas of assimilation (that immigrants should adopt white, English-speaking American culture), multiculturalism (the idea that groups should retain their distinctive identities and pursue political representation as groups), the economic impact of immigration, the impact of illegal immigration, and the role of languages other than English in public life.

President Johnson signs the Immigration and Nationality Act at the foot of the Statue of Liberty

The Johnson administration supported the reform of the immigration laws, proposed by Democratic congressmen. The act would profoundly alter the nation's demographics.