Immigrants

After 1870, the use of steam-powered ships with lower fares became prevalent. Meanwhile, farming improvements in southern and eastern Europe created surplus populations. This "wave" of migration could better be referred to as a "flood" of immigrants, as nearly 25 million Europeans made the voyage. Italians, Greeks, Hungarians, Poles, and others constituted the bulk of this migration. Included among them were 2.5 to 4 million Jews.

While most immigrants were welcomed, Asians were not. Many Chinese had been brought to the West Coast to construct railroads, but unlike European immigrants, they were seen as being part of an entirely alien culture. After intense anti-Chinese agitation in California and the West, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882. An informal agreement in 1907, the Gentlemen's Agreement, stopped Japanese immigration. Each group evinced a distinctive migration pattern in the gender balance within the migratory pool, the permanence of their migration, their literacy rates, and the balance between adults and children. Asians made up the bulk of the U.S. industrial labor pool, making possible the emergence of such industries as steel, coal, automobile, textile, and garment production, and enabling the United States to leap into the front ranks of the world's economic giants.

Ellis Island

Ellis Island, in Upper New York Bay, was the gateway for more than 12 million immigrants to the United States as the nation's busiest immigrant inspection station from 1892 until 1954. In the 35 years before Ellis Island opened, more than eight million immigrants arriving in New York City had been processed by New York State officials at Castle Garden Immigration Depot in Lower Manhattan, just across the bay. The federal government assumed control of immigration on April 18, 1890, and Congress appropriated $75,000 to construct America's first federal immigration station on Ellis Island. Artesian wells were dug, and landfill was hauled in from incoming ships' ballast and from construction of New York City's subway tunnels, which doubled the size of Ellis Island to more than six acres. While the building was under construction, the Barge Office nearby at the Battery was used for immigrant processing.

The first station was an enormous three-story-tall structure, with outbuildings, built of Georgia pine, containing all of the amenities that were thought to be necessary. It opened with celebration on January 1, 1892. Three large ships landed on the first day, and 700 immigrants passed over the docks. Almost 450,000 immigrants were processed at the station during its first year.

Xenophobia

Immigrants' urban destinations and numbers and an overall antipathy toward foreigners led to the emergence of a wave of organized xenophobia. By the 1890s, many Americans—particularly those from the ranks of the well to do, white, and native born—considered immigration to pose a serious danger to the nation's health and security. In 1893, a group called the "Immigration Restriction League," along with other similarly inclined organizations, began to press Congress for severe curtailment of foreign immigration.

Irish and German Catholic immigration was opposed in the 1850s by the Nativist/Know-Nothing movement, originating in New York in 1843 as the American Republican Party (not to be confused with the modern Republican Party). It was empowered by popular fears that the country was being overwhelmed by Catholic immigrants, who were often regarded as hostile to American values and controlled by the Pope in Rome. Active mainly from 1854–1856, the movement strove to curb immigration and naturalization, though its efforts met with little success. There were few prominent leaders, and the largely middle-class and Protestant membership fragmented over the issue of slavery, most often joining the Republican Party by the time of the 1860 presidential election.

Legislation

Shortly after the U.S. Civil War, some states started to pass their own immigration laws. This prompted the U.S. Supreme Court to rule in 1875 that immigration was a federal responsibility. In 1875, the nation passed its first immigration law, the Page Act of 1875, also known as the "Asian Exclusion Act." This outlawed the importation of Asian contract laborers, any Asian woman who would engage in prostitution, and all people considered to be convicts in their own countries.

In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act. The act stated that there was a limited amount of immigrants of Chinese descent allowed into the United States. The law was renewed in 1892 and 1902. Prior to 1890, the individual states regulated immigration into the United States. The Immigration Act of 1891 established a commissioner of immigration in the Department of the Treasury. The Canadian Agreement of 1894 extended U.S. immigration restrictions to Canadian ports.

Settlement of Immigrant Populations

About 1.5 million Swedes and Norwegians immigrated to the United States within this period due to opportunity in America and poverty and religious oppression in united Sweden-Norway. This accounted for around 20 percent of the total population of the kingdom at that time. They settled mainly in the Midwest, especially Minnesota and the Dakotas. Danes had comparably low immigration rates due to a better economy; after 1900, many Danish immigrants were Mormon converts who moved to Utah.

More than two million eastern Europeans, mainly Catholics and Jews, immigrated between 1880 and 1924. People of Polish ancestry are the largest eastern European ancestry group in the United States. Immigration of eastern Orthodox ethnic groups was much lower.

New York and other large cities of the East Coast became home to large Jewish, Irish, and Italian populations, while many Germans and central Europeans moved to the Midwest, obtaining jobs in industry and mining. At the same time, about one million French Canadians migrated from Quebec to New England. Lebanese and Syrian immigrants started to settle in large numbers in the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century. The vast majority of the immigrants from Lebanon and Syria were Christians, but smaller numbers of Jews, Muslims, and Druze also settled. Many lived in New York City and Boston. In the 1920s and 1930s, a large number of these immigrants set out west, with Detroit getting a large number of Middle Eastern immigrants, as well as many Arabs working as farmers in Midwestern areas.

From 1880 to 1924, around two million Jews moved to the United States, mostly seeking better opportunity in America and fleeing the pogroms of the Russian Empire. After 1934, these Jews, along with any other above-quota immigrants, usually were denied access to the United States.

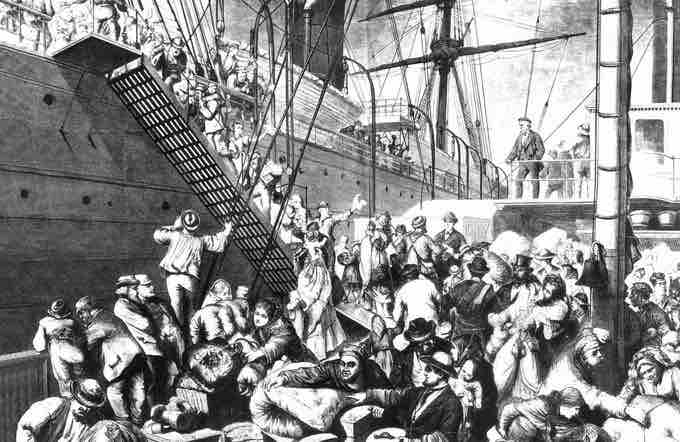

"From the Old to the New World"

An illustration published in Harper's Weekly in 1874 shows German emigrants boarding a steamer in Hamburg, Germany, to come to America.