If you don't use salts, the hacker can simply type them into Google and likely find it. MD5 encrypt your password, then Google the result, and you'll see what I mean.

If you've chosen a sufficiently complex password, then it probably won't be on Google, but it will still be in pre-computed tables called "rainbow tables" (the full tables would take too much space, so the "rainbow" technique is used to compress them).

If no tables are being used, then it doesn't matter if the password is salted or not. Of course, tables are always used, so yes, you should salt the passwords.

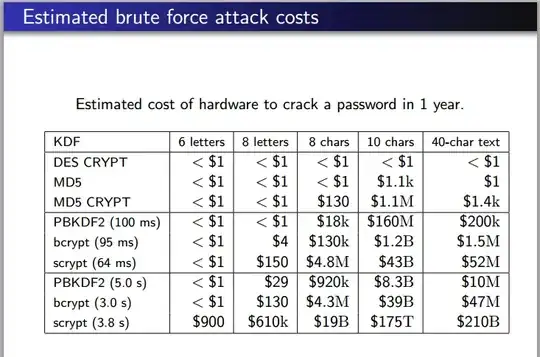

A desktop machine, with a gaming card (which can also be used to accelerate password cracking), and calculate a billion hashes/second. How fast this cracks your password depends. It can calculate all combinations for short passwords within a few minutes. But the, the problem is exponential, so that it cannot calculate all possible combinations for long passwords, even if you used a billion computers over a billion years.

Instead, what hacker do is a "mutated dictionary" crack. They start with a list of well-known words. It's called a "dictionary", but such lists contain a lot of words that you wouldn't find in a real dictionary, like "ncc1701", the designation for the Star Trek Enterprise. For each word, it does a number of mutations, such as capitalizing some letters, changing some letters to numbers, like "p4ssw0rd", or appending characters, like "password1234". How fast this works depends upon the skill of the hacker choosing just the right dictionary and just the right mutations. This can also change depending upon the hacker's knowledge of you. For example, if you are Hispanic, the hacker will add Spanish words and names to the dictionary.

You can expect that if your password database is stolen, the hacker will be able to crack about half of the salted passwords with a couple day's worth of work.