On July 28, 1914, World War I began with the Austro-Hungarian invasion of Serbia, followed by the German invasion of Belgium, Luxembourg, and France, and a subsequent Russian attack against Germany. The United States, however, did not join the conflict until April 1917.

Maintaining U.S. Neutrality

Under President Woodrow Wilson, the U.S. maintained a policy of non-interventionism, avoiding participation in the conflict while trying to broker a European peace, which was characterized as neutrality "in thought and deed." Apart from an Anglophile element supporting the British, public opinion initially favored neutrality. The sentiment was especially strong among Irish-, Swedish-, and German-Americans, as well as many women, church leaders, and farmers, particularly those in the South.

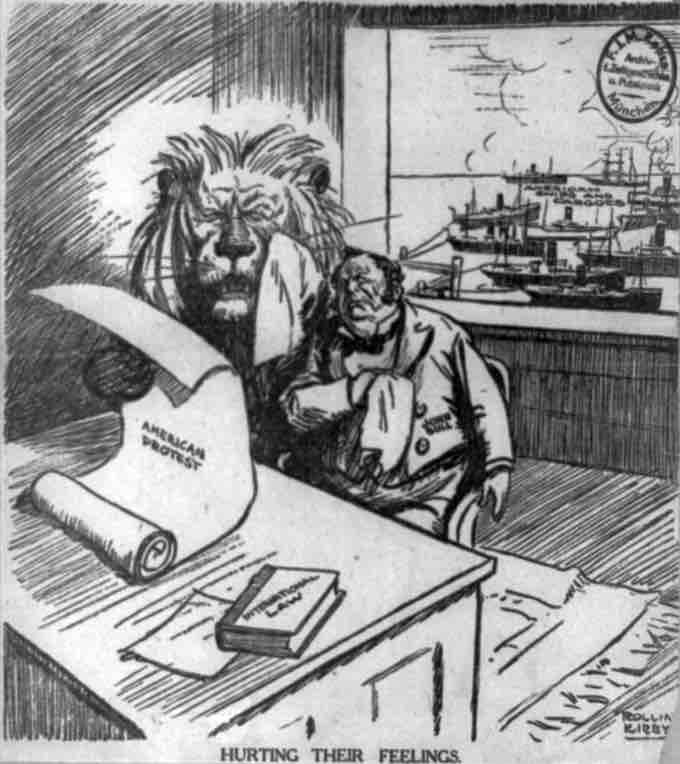

"Hurting Their Feelings"

Political cartoon showing British characters crying as American warships sit in the harbor, maintaining neutrality in the European conflict.

Wilson kept the economy on a peacetime scale, allowing large-scale loans to Britain and France but making no preparations for war and keeping the army at normal levels, despite increasing demands from Republicans for the Democratic president to increase military preparedness. The American public increasingly came to see Germany as the villain after news of atrocities following the invasion of Belgium in 1914 and the 1915 sinking of the British passenger liner RMS Lusitania by a German U-Boat, in defiance of international law.

British World War I Propaganda: Lusitania

This British propaganda poster urging participation in World War I shows the RMS Lusitania sinking in the background.

The most important indirect strategy used by the belligerents in the war was the naval blockade. The British Royal Navy successfully stopped the shipment of most war supplies and food to Germany, including by neutral American ships that were seized or turned back. The British frequently violated America's neutral rights by seizing ships, causing presidential adviser Colonel Edward M. House to comment, "The British have gone as far as they possibly could in violating neutral rights, though they have done it in the most courteous way." When Wilson protested British violations of American neutrality, the British backed down, but still armed most merchant ships with medium-caliber guns that could sink submarines venturing above the surface.

Germany also used a blockade. "England wants to starve us," said Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, the man who built the German fleet and remained a key adviser to the Kaiser Wilhelm II. "We can play the same game. We can bottle her up and destroy every ship that endeavors to break the blockade." Tirpitz reasoned that the British Isles depended on imports of food, raw materials, and manufactured goods, therefore blocking a substantial number of ships from making these deliveries would effectively undercut Britain’s long-term ability to maintain an army on the Western Front.

Unable to challenge the more powerful Royal Navy on the surface, Germany relied on submarines. Possessing only nine long-range U-boats as the war began, Germany nevertheless had ample shipyard capacity to build hundreds more. German U-Boats torpedoed ships without warning, but claimed its submarines dared not surface near armed merchant ships and were too small to rescue passengers and crew, leaving many to drown in the frigid waters surrounding the United Kingdom.

German Submarine Zone, February 1915

Map showing submarine warfare zone around the United Kingdom, declared by Germany on February 18, 1915.

U-Boats and the U.S.

The United States, however, demanded respect for international law, which protected neutral American ships on the high seas from seizure or sinking by any belligerent in the conflict. In February 1915, the U.S. warned Germany about misuse of submarines, but on May 7, Germany torpedoed the Lusitania, resulting in the loss of 1,198 civilians, including 128 Americans. The sinking of a large, unarmed passenger ship, combined with stories of atrocities by German troops occupying Belgium, shocked Americans and turned public opinion hostile to Germany, although not yet to the point of war . Wilson issued another warning to Germany that it would face "strict accountability" if it sank neutral U.S. passenger ships. Berlin acquiesced, ordering its submarines to avoid passenger ships.

Sinking of the Lusitania

1915 painting depicting the sinking of the Lusitania by the German U-Boat U-20.

In January 1917, however, German Field Marshal Hindenburg and General Ludendorff decided that an unrestricted submarine blockade was the only way to break the stalemate with the Allies on the Western Front. At their urging, Kaiser William II ordered that unrestricted submarine warfare should be resumed. German war planners knew this meant the United States would most likely enter the conflict, but gambled that it would take America more than a year to mobilize its forces enough to be a threat on the Western Front, allowing sufficient time for Germany to be victorious. The civilian government in Berlin objected, but the Kaiser sided with his military. As expected, this fateful move played a large part in American’s pivotal decision to end its neutrality and join the Allied war effort.